UNESCO House - An Art Museum in Paris You Didn't Know About

Nov 10, 2017

Right in the heart of Paris, in the popular 7th arrondissement, just one and a half kilometers southeast of the Eiffel Tower, a secret art museum hides in plain sight in a place called UNESCO House. Also called the World Heritage Center, UNESCO House is the headquarters of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). This stunning complex of Modernist buildings has long been admired for its architecture. The nine-person design team that originally created it included representatives from Brazil, France, Italy, Sweden and the United States. Some of the most influential architects of the 20th Century were on the team, including Marcel Breuer, Charles Le Corbusier, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Lucio Costa, the designer of Brasilia, the capital of Brazil, itself a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to its stunning collection or artful buildings and public spaces. But few people today realize that the UNESCO House is also the caretaker of one of the most important art collections in the world. Within the walls of those architectural gems, and all around them on the grounds and in the gardens, hundreds of artworks by the most influential artists of the past 600 years are on public view year round, free of charge. Any time you are in Paris you can visit UNESCO House and get a glimpse of some of the works. But if you want a private tour to see even more of the works in this secret museum, all that is required is to send an email to visits@unesco.org. But beware: it can take many weeks to receive approval, so do not hesitate! Meanwhile, while you wait, here is the story of this one-of-a-kind art collection, along with a sampling of some of the unforgettable works of art you can expect to find there when you visit.

Utopian Dreams

UNESCO is part of the United Nations. So to fully understand its history and purpose, we must first look at when and why the UN was founded. The charter that formed the United Nations was enforced on 24 October 1945, less than two months after the end of World War II. The charter was first signed months earlier, while the war was still raging. And the need for its existence grew out of ideas that were first expressed years earlier, all the way back in 1941, in a document called the Atlantic Charter. The Atlantic Charter was basically a plan for what the Allied Powers wanted the world to be like after they won World War II. It was a utopian manifesto predicated entirely on the hopeful notions that, first of all, the Axis Powers could be defeated, and second of all that the populations they commanded could be brought back together into the peaceful community of nations. The charter included wonderful goals, such as improved economic and social conditions for all people, free use of international waters, eliminating military force as a way of achieving political change, and self-determination and self-governance for all nations. So when the UN was finally formed, it was seen by the signatory nations as the embodiment of these ideals.

So in essence, UNESCO is basically the cultural arm of the UN. It represents the idea that human culture transcends the culture of any one nation, and as an organization it brings together representatives from all nations in order that they can work to ensure that the culture of humanity is understood and preserved for future generations. Of course, just like the UN, UNESCO is not without its detractors. Some countries see it as an organization that interferes with their internal politics and developmental plans. Others feel it only really represents an agenda of 1st world nations, and puts too much emphasis on history instead of prioritizing the contemporary needs of populations that are struggling to survive. Nothing is perfect, after all, and sometimes the goals of the UN and UNESCO do clash with those of certain political powers. But the ideals UNESCO represents were born out of one of the darkest periods in human history. And the programs and initiatives it adopts are intended to prevent another global armed conflict from ever occurring again.

The Art Collection

After the end of World War II, UNESCO began its existence in the Hotel Majestic, today known as the Peninsula, on the Avenue Kléber in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. The building was a bit of a shambles following the war, and office workers occupied bedrooms and bathrooms, some infamously keeping their papers stacked in bathtubs for lack of space. Back then, the notion that UNESCO should be the caretaker of a historic art collection might have sounded crazy. But by the time UNESCO House was inaugurated in 1958, it was a much different story. In fact, it was clear as soon as the designs were finalized that the buildings would architectural monuments to peace and prosperity. So the idea spread quickly that every member nation of the UN should donate a work of art to UNESCO to represent their unique cultural heritage. Some nations contributed works that spoke in a general way to their history. For example, when you visit UNESCO House you might notice a large-scale Zen garden on the grounds. This garden was a gift from the nation of Japan. But most other countries took the opportunity to ask their most famous living artists to contribute a work of art in order to promote their culture as modern and relevant to the current moment.

Pablo Picasso - The Fall of Icarus, 1958, monumental mural adorning the walls inside UNESCO World Headquarters in Paris, image courtesy of the UNESCO Works of Art Collection

Pablo Picasso - The Fall of Icarus, 1958, monumental mural adorning the walls inside UNESCO World Headquarters in Paris, image courtesy of the UNESCO Works of Art Collection

The most famous Spanish-born artist at the time was Pablo Picasso. Back in 1944, Picasso had joined the Communist party, so he was not politically aligned with the idealistic vision UNESCO represented. Nonetheless, he agreed to design a mural for UNESCO as long as he could be left alone to determine the subject matter. When he completed the mural, which is called The Fall of Icarus, he and a group of his students protested its opening—a testament to the mixed emotions this artists had toward politics. Meanwhile, his countryman, Joan Miró, was also invited to contribute a work of art to UNESCO House. He used the opportunity to create a pair of ceramic walls. Miró had been experimenting with ceramics for more than a decade, but this was his most ambitious ceramic project at that time. He created two walls made of hand fired ceramic tiles. On one he painted a mural called Wall of the Moon, and on the other he painted a mural titled Wall of the Sun. He would later go on to make many more of these walls, despite the fact that this particular one was plagued with setbacks and difficulties.

Site Specifics

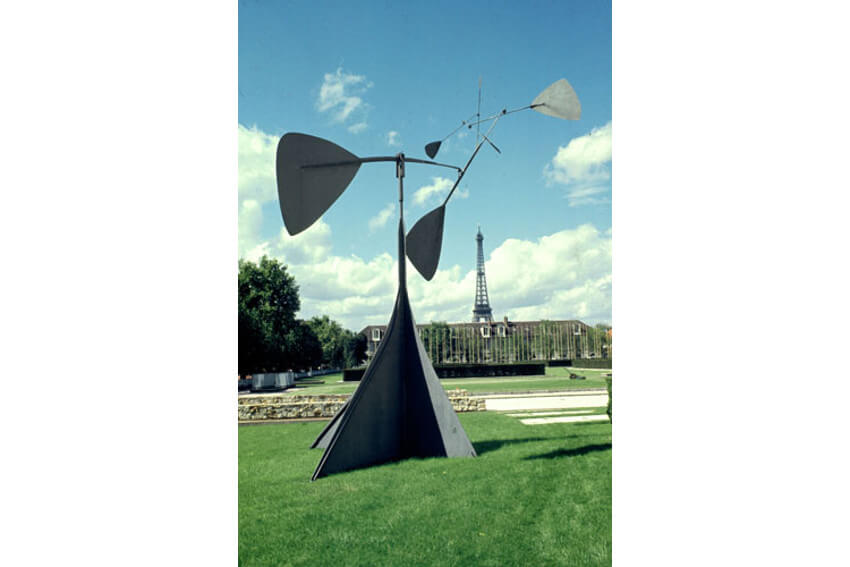

One of the specific requests made by UNESCO is that all artworks take into account the architecture of the site. The artworks are essential to the vision of UNESCO, but since the buildings themselves are considered works of art, it is a priority that so artworks compete with the structures or the grounds aesthetically. One of the most famous examples of an artist honoring this request came from the American-born artist Alexander Calder. When he was invited to contribute a work of art for the UNESCO House, he set about designing a piece that could be installed outside on the grounds. The piece he made is called Spirale. A solid black, biomorphic mobile, it rests atop a tower that mimics the shape of the Eiffel Tower, which can be seen rising elegantly behind it.

Spirale, a site specific mobile installed in the gardens of UNESCO House by Alexander Calder, made in 1958, image courtesy of the UNESCO Works of Art Collection

Spirale, a site specific mobile installed in the gardens of UNESCO House by Alexander Calder, made in 1958, image courtesy of the UNESCO Works of Art Collection

Other artists who have work included in the permanent UNESCO House collection include Alberto Giacometti (representing Switzerland), Henry Moore (representing the United Kingdom), Victor Vasarely (representing Hungary), Eduardo Chillida (representing Spain), Carlos Cruz-Diez (representing Venezuela), Rufino Tamayo (representing Mexico), Karel Appel (representing the Netherlands) and Afro Basaldella (representing Italy). But perhaps the most powerful example of an artist honoring the legacy of UNESCO House is when, in 1995, Japanese architect Tadao Ando added his Space of Meditation to the collection. The cylindrical concrete structure that holds this sacred aesthetic space was originally located in Hiroshima. It survived the nuclear explosion there in 1945. The building was decontaminated and moved to the UNESCO House grounds. Ando competed with architects from around the world. His proposal, which offers visitors a contemplative sanctum, feels as though it was original to the Modernist plan of its surroundings. And its history as a resurrected relic of war speaks to the idea of redemption and hope that UNESCO stands for.

Featured image: UNESCO - logo

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio