Le Corbusier - Between Architecture and Fine Art

Within the contemporary architecture community, the name Le Corbusier is as likely to arouse praise as derision. One of the most influential thinkers of the 20th Century, Le Corbusier was more than an architect. He was also a multi-disciplinary artist, designer and philosopher. In the writings of Le Corbusier, art and architecture are presented as two vital and inseparable parts of a single phenomenon, one that when conceived of and implemented correctly has the power to transform society. Born Charles Édouard-Jeanneret in 1887, in a small town in the Swiss Alps, Le Corbusier was the child of a watch maker and a music teacher, who spent many a childhood day traipsing through the woods exploring nature. By the time he died in 1965, this simple country boy had developed an aesthetic worldview that led to the creation of the first truly modern, and truly global architectural style. His ideas were idealistic, bordering on Utopian. They were devoid of local, partisan, and nationalist influences, and were geared solely toward fulfilling the needs of humanity in a universal sense. His approach, which eventually became known as the International Style, was massively influential in its day, but the legacy it left behind is controversial. Many contemporary architects view its brutish, monotonous look as the source of some of the most depressing failures in modern urban planning. Others see it as uniquely beautiful, and something that might still hold promise if revisited thoughtfully and in the original spirit of the movement. But regardless of whether one sees the work of Le Corbusier as brilliant or horrifying, beautiful or horrific, inspired or insipid, the fact remains that no architect working today can deny the impact of his ideas, and no resident of a major, modern, metropolitan area can escape his influence.

The Building Blocks of Architecture

It is wholly appropriate that today Le Corbusier is mostly remembered for his architecture. In his lifetime he worked on hundreds of architectural projects and designed a multitude of influential buildings around the globe. But it is important to point out that Le Corbusier was an artist first. He had no formal education in architecture. In fact, he had little official training in anything at all, having dropped out of primary school at age 13. Most of the early aesthetic training he received came from his own research in the local library and from his personal observations.

Le Corbusier also derived a great deal of inspiration from time spent playing with something called Froebel Blocks. Considered the first educational toy ever marketed, Froebel Blocks are building blocks that include a mix of cubes, cones, pyramids, spheres and other geometric forms. Rather than simply allowing kids to stack up piles of squares, Froebel Blocks allow for complex architectonic constructions. It is interesting to note, in fact, that Frank Lloyd Wright also played with Froebel Blocks as a child, and some of his most famous designs, such as his Prairie Homes, can be constructed out of a set of the blocks.

Le Corbusier - Eglise Saint-Pierre de Firminy

Le Corbusier - Eglise Saint-Pierre de Firminy

The Art of Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier studied the forms in Froebel Blocks then taught himself to recognize those forms in the architecture he saw as he traveled around the world. He noticed the repetition of those basic forms in buildings dating all the way back to the earliest periods of human civilization. As a young man, Le Corbusier filled scores of sketchbooks with drawings of global architecture, focusing on these essential forms in his drawings. He used the drawings to create a pure visual language that he then later expressed in his paintings.

His still life paintings of geometric forms straddle the line between apparent abstraction and something utterly concrete. They boil down the visual language of the world to its most pure geometric elements. We can see in them the foundation of the ideas that later informed his architectural accomplishments. As Le Corbusier once explained, “Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light. Our eyes are made to see forms in light; light and shade reveal these forms; cubes, cones, spheres, cylinders or pyramids are the great primary forms which light reveals to advantage; the image of these is distinct and tangible within us without ambiguity. It is for this reason that these are beautiful forms, the most beautiful forms. Everybody is agreed to that, the child, the savage and the metaphysician."

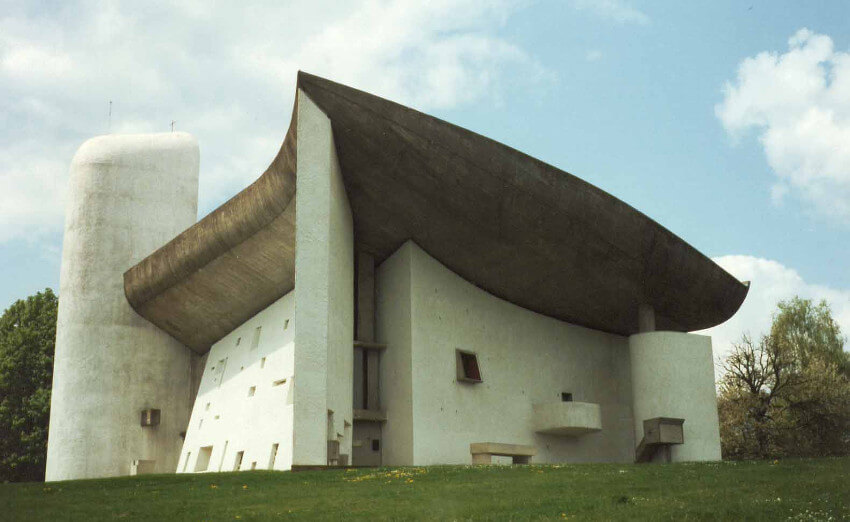

Le Corbusier - Chapel of Note-Dame-Du-Haut

Le Corbusier - Chapel of Note-Dame-Du-Haut

Learning His Craft

Although he was generally opposed to school, Le Corbusier did briefly attend art classes from the age of about 21 to 24 at the local art school in his hometown of Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland. He did not take any architecture classes while there, but he did discuss architectural concepts with his art teachers. And while attending the school he also completed his first architectural design, for a mountain chalet called the Villa Fallet. The design of the building, which is notable for its steep, A-frame roofs, relied on a mixture of traditional natural materials such as wood and stone and subtle geometric references in the construction.

After leaving art school, Le Corbusier embarked on a period of travel and apprenticeships. He went to the great cities of Europe, sketching, painting and writing, and developing his ideas about the importance of light, space, and order as they relate to human happiness. From 1908 till 1910 he visited Paris, where he found work as an assistant to Augueste Perret, a French architect who at the time was an early proponent of using the controversial, modern material known as reinforced concrete. Then Le Corbusier moved to Berlin, where he found work in the studio of Peter Behrens, an influential architect who was known for applying cutting edge modern design principals to industrial architecture. It was at that job where Le Corbusier met and befriended two other aspiring architects who also happened to be working as assistants in the studio: Walter Gropius, who would soon go on to be a founding member of the Bauhaus; and Mies van der Rohe, who would go on to be one of the most influential Modernist architects of the 20th Century.

Villa Fallet, located in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, designed by Le Corbusier in 1905. © FLC/ADAGP

Villa Fallet, located in La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland, designed by Le Corbusier in 1905. © FLC/ADAGP

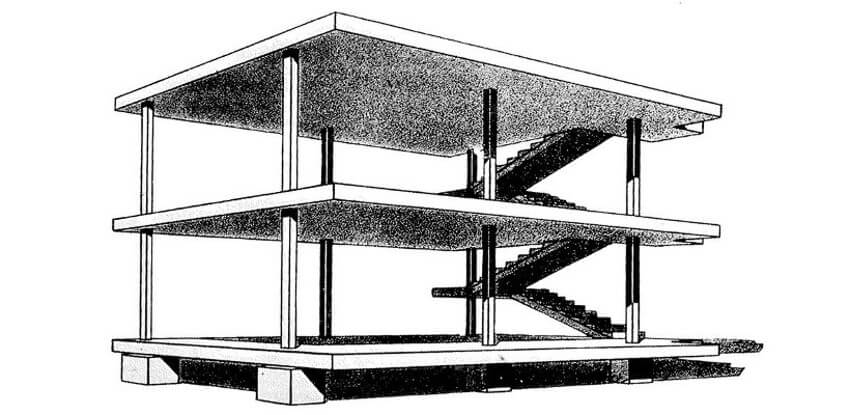

The Impact of War

Following the outbreak of World War I, Le Corbusier returned to his hometown in neutral Switzerland, where he supported himself as a teacher and a designer of houses. During this time he applied for a patent for what he called his Dom-ino house. The basic idea of the Dom-ino house is that pillars along the outer edge of the structure support the entire weight of the building, so that the living area can consist of long, flat expanses made of concrete slabs. The design allowed for living spaces to be completely open, allowing a maximum of light and space, and letting the human inhabitants order the interior space any way they choose.

The Dom-ino house was representative of a larger philosophy Le Corbusier was developing, which in essence was based on the idea that proper urban planning and good architecture could prevent the world from experiencing events such as war and revolution. Social unrest, he believed, was arising from the fact that urban centers were poorly designed to accommodate large populations, a fact that was leading to a series of emotional crises for the masses who were being forced to live in situations that were not suited to the demands of their lives and livelihoods. After the end of World War I, Le Corbusier moved to Paris and gave his philosophy a name. He called it Purism, because of its reliance on pure geometric forms. He spent several years in Paris avoiding architecture all together, instead expressing his Purist aesthetic through painting. Then in 1920, he began publishing a magazine called L’Esprit Nouveau, in which he wrote extensively about the potential practical applications of his Purist philosophy in the fields of architecture and urban planning.

Dom-ino House plans, patented by Le Corbusier in 1915

Dom-ino House plans, patented by Le Corbusier in 1915

Rebuilding the World

One of the key elements to arise out of his writings in L’Esprit Nouveau was a sort of architectural manifesto, which Le Corbusier referred to as the Five Points. The Five Points would eventually form the basis for the thinking that helped define the International Style. The five points were: Pilotis: the idea that a building should be entirely supported by columns on the outer edge of the structure; Open Floor Plans: the idea that because the pilotis support the weight of the building, the interior floor plan could be completely open; The Open Facade: since the pilotis support the weight of the building, the exterior could adopt a pared down, utilitarian look; Horizontal Windows: since the walls need not support any weight, the entire length of a building could be made of glass, allowing maximum amounts of light to come in, blending the interior and exterior worlds; and The Garden Roof: the idea that every building, because it would be flat, could contain a nature space on its roof, which the inhabitants could access.

Le Corbusier and his contemporaries who collaborated with him on the creation of the International Style believed these modern approaches to architecture were perfectly suited to the job of rebuilding cities after World War I. Although he was notoriously difficult to work with, Le Corbusier nonetheless traveled the world taking design commissions and lecturing on his ideas. Following the stock market crash of 1929, Le Corbusier found it increasingly difficult to make a living, and as such opened his mind to the possibilities that other systems besides capitalism might be best for society. He even accepted invitations from fascist leaders like Benito Mussolini to speak about his architectural philosophy, earning him a reputation in the minds of many critics as someone without principles, willing to work for whoever pays him.

Le Corbusier - La Ville radieuse (The Radiant City), 1935

Le Corbusier - La Ville radieuse (The Radiant City), 1935

The Soul of Space

But Le Corbusier was truly nothing if not principled. He simply wanted a better world, and believed it could be created through modern architecture and design. And that, he came to learn, could be achieved in virtually any political climate. After World War II, his ideas flourished, and two massive projects he completed came to define his legacy for many of his fans. One was a public housing project in Paris called Unité d'Habitation. The geometric, brutish-looking building had enough different kinds of apartments in it that it was capable of accommodating a huge range of family sizes, from one person up to ten people. Its construction incorporated the Five Points, and included a rooftop terrace for residents. The building also included a grocery market, schools, a gym, a hotel, a restaurant and other commercial services for the residents, making it a predecessor of the mixed-use communities of today.

Next, Le Corbusier was invited to India, where he spent a decade working on his most ambitious creation: an entire planned city. Indian officials needed a new capital city for Punjab. Drawing on all of the ideas he had developed over the course of his professional career, Le Corbusier created the city of Chandigarh on a perfectly ordered grid, laying out each district so it possessed all of the necessary elements to support a vibrant, active community. He divided the city into different zones to support different types of economic activity, and built the whole environment around a centralized park with a lake. Although the architecture is considered monotonous looking today, residents of the city are consistently named the happiest people in India. If for no other reason than that, we must admit that there is something valuable about the legacy of Le Corbusier. Somewhere in his efforts he arrived at what could be called the soul of architecture: that hard-to-define essence that transforms a building into something more closely resembling a work of art.

Featured image: Villa Savoye, located in the Parisian suburb of Poissy, built by Le Corbusier in 1931, typifying his Five Points philosophy

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio