Miró on Miró: A Glimpse Inside an Artist's Mind

Jan 24, 2016

This week a major exhibition of the work of Joan Miró is ending, just as a fascinating glimpse at his process begins. Since October of last year, The Kunsthaus Zürich has been hosting a retrospective of Miró's career. The show of murals, paintings and sculptures dating from 1924 to 1972 concludes on 24 January, 2016. Opening on 21 January, Mayoral, at 6 Duke Street in London, presents a one-of-a-kind exhibition titled Miró's Studio. As the name implies, the show replicates the artist's workspace, as it existed from 1956 forward on the island of Majorca in Spain. The artist's grandson, Joan Punyet Miró, an art historian, collaborated in the precise recreation of the space.

Rarely is such a glimpse of an artist's process available. But since Miró was also an avid commentator and writer, he did leave behind many of his own words by which we may also know what he was thinking. So as we prepare to contend with whatever insights may be revealed by this journey into Miró's Studio, we’d thought we'd also take a quick look back at some lesser-known highlights of this influential artist's life and career, as described in his own words.

Miró Wasn’t Neutral

"In the current struggle I see the antiquated forces of fascism on one side, and on the other, those of the people, whose immense creative resources will give Spain a drive that will amaze the world." - Joan Miró

Miró was born to middle class parents in Spain in 1893. Though Spain was officially neutral in World Wars I and II, Miró did serve in the Spanish military, as was the duty of all young Spanish men who could not afford to buy themselves out of it. Miró was raised in an atmosphere of intense political and social change. Spain's status as a world power had recently collapsed, but the country's neutral status attracted many great European artists to Barcelona, where Miró lived and worked. He formed lasting relationships with many great artists of his time, which proved to be a major influence on his work and life.

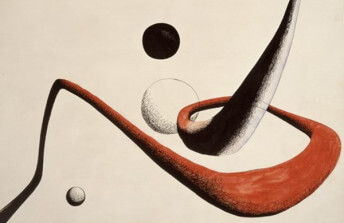

Joan Miró - The Sun (El Sol), 1949. Screenprint on canvas. Composition: 126.3 × 191.2 cm; sheet: 126.3 × 197 cm. Edition: 200. Gift of James Thrall Soby. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Miró Was Friends With Alexander Calder

"When I first saw Calder’s art very long ago I thought it was good, but not art." - Joan Miró, quoted in the New York Times, referencing his encounter with Alexander Calder's Circus in 1928.

Over the course of their lives, Miró and Calder developed a strong bond of friendship and professional respect. At one point, when Miró began working seriously with sculpture, he wrote to Calder praising him for his own work in that medium:

" I have looked at them (your sculptures) many times, and they are something completely unexpected. You are taking a path full of great possibilities. Bravo!"

When Calder, whom Miró called Sandy, passed away in 1976, Miró had come to rely on him as one of his closest associates. He wrote this poem for him when he passed:

"Your face had become dark, and, upon the day’s awakening, your ashes will disperse themselves throughout the garden. Your ashes will fly to the sky, to make love with the stars. Sandy, Sandy, your ashes caress the rainbow flowers that tickle the blue of the sky."

Joan Miró - Still Life I, Montroig and Paris, July 1922-spring 1923. Oil on canvas. 14 7/8 x 18 1/8" (37.8 x 46 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

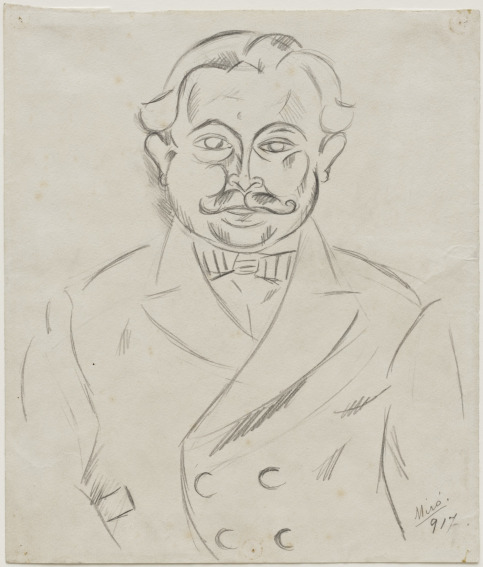

Miró's Early Work Was Despised

Miró felt style was a trap. He believed in the artist's obligation to seek free methods of expression.

"Poetry and painting are done in the same way you make love; it's an exchange of blood, a total embrace - without caution, without any thought of protecting yourself." - Joan Miró

Miró's first exhibition was in 1918. His paintings were a rejection of existing styles, especially Spanish styles. Though they in almost no way resemble his later avant-garde work, they were perceived at the time as scandalous. Many of the works in the show were damaged or destroyed by outraged viewers.

Joan Miró - Man with a Moustache, 1917. Pencil on paper. 10 3/4 × 9 1/8" (27.3 × 23.2 cm). Gift of the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

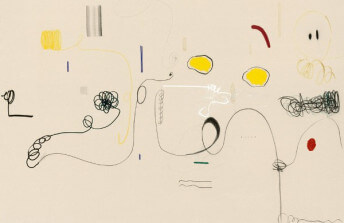

Miró Didn't Consider Himself to Be an Abstractionist

On the contrary, he considered his work to be representative. In some cases it represented images he saw in his own mind. In other instances it represented the essence of objects and living things. He was tireless in his search for ways to represent what he perceived, and spoke often about his process.

"Have you ever heard of anything more stupid than ‘abstraction-abstraction’? ...as if the marks I put on a canvas did not correspond to a concrete representation of my mind..." - Joan Miró

"How did I think up my drawings and my ideas for painting? Well I’d come home to my Paris studio…I’d go to bed, and sometimes I hadn’t any supper. I saw things…I saw shapes on the ceiling...and I jotted them down in a notebook." - Joan Miró

Miró's Studio runs until 12 February 2016, at Mayoral, 6 Duke Street, St. James's, London.

Featured image: Joan Miró, Son Abrines, 1978, Photo by: Jean Marie del Moral.

All images used for illustrative purposes only