Alexander Calder Mobile Art and Its Many Forms

Aug 8, 2016

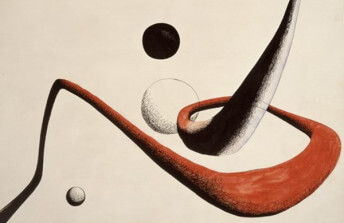

Whether we’re aware of it or not, everything is moving all the time. The earth is spinning on its axis and orbiting the sun. Every molecule within us is vibrating, spinning and morphing. Movement orchestrates life’s delicate, beautiful chaos. Alexander Calder knew this essential fact of life. He devoted most of his career to expressing movement’s beauty. Calder’s mobiles, abstract, kinetic sculptures designed to move freely in space, communicated better than any art that came before them that along with form, mass, time and space, movement is an essential factor that defines the physical universe. The enormous body of work Calder created over the course of his life included drawings, paintings, lithographic prints, jewelry, stage decorations, costumes and sculpture, and left a legacy of whimsy, beauty and wonder. His seemingly endless ability to innovate, along with his love of hard work, made him one of Modernism’s most influential artists, as well as one of its most universally beloved.

They Called Him Sandy

Alexander Calder was born in a small town in Pennsylvania in 1898 to parents who were both artists. It was in his father’s studio that Calder made his first work of art, a clay elephant, sculpted by hand when his was four years old. Calder’s parents demonstrated their approval of their son’s natural artistic disposition by setting the young “Sandy” up with his own studio when he was eight years old, in the cellar of their home on Euclid Avenue, in Pasadena, California. Recalling that time in his life, Calder once said, “My workshop became some sort of a center of attention; everybody came in.” Most of the objects Calder made as a child in his basement studio were animal forms composed of found materials, especially discarded copper wire he and his sister picked up from the street after it was left behind by electrical workers.

Calder would later accomplish wonderful things with wire. And that wasn’t the only childhood influence that would affect his later work. Movement was a tremendous factor in his upbringing. That house in Pasadena was the third home Calder had lived in by the time he was eight years old. And his family would move eight more times by the time he started college. Despite being rootless, Calder remained focused and good humored and maintained a small studio space wherever his family landed. Louisa James, who married Calder in 1931, wrote to her mother after getting engaged: “To me Sandy is a real person which seems to be a rare thing. He appreciates and enjoys the things in life that most people haven't the sense to notice. He has tremendous originality, imagination, and humor which appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile. He enjoys working and works hard, and thus ends the summary of his character.”

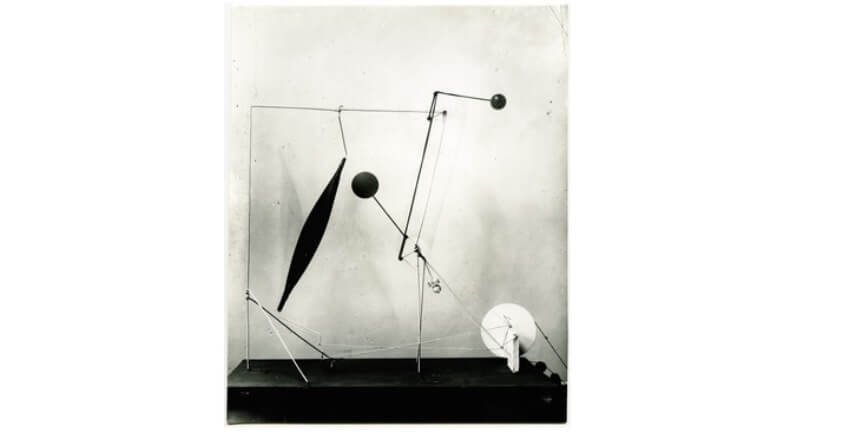

Alexander Calder - Untitled, kinetic wire sculpture, 1931, the mobile that impressed Duchamp. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York

Calder’s Circus

At 21, Calder graduated college with a degree in Mechanical Engineering. He was an expert draftsman, and immediately started moving around the United States taking assignments with a host of different companies. While working he was always also taking art classes. At age 26, he landed his first official job as a creative artist, illustrating for a newspaper called the National Police Gazette. An assignment for that job to cover the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus changed Calder’s life. He fell in love with the circus, saying, “I was very fond of the spatial relations. I love the space of the circus. I made some drawings of nothing but the tent. The whole thing of the—the vast space—I’ve always loved it.”

Calder started painting animals and adapting store-bought toys to mimic the movement of circus routines, and he also returned to making wire sculptures or people and animals. Then at age 28, while living in Paris, these influences all came together and Calder created what would become one of his most iconic works of art: the Calder Circus. Using wire, fabric, wood and plastic, he created a miniature replica of a working circus that he could operate in a small and then pack away inside a suitcase. Calder himself operated the kinetic forms in the circus, resulting in a unique artwork that incorporated wire sculpture, kinetics and performance art into one aesthetic event.

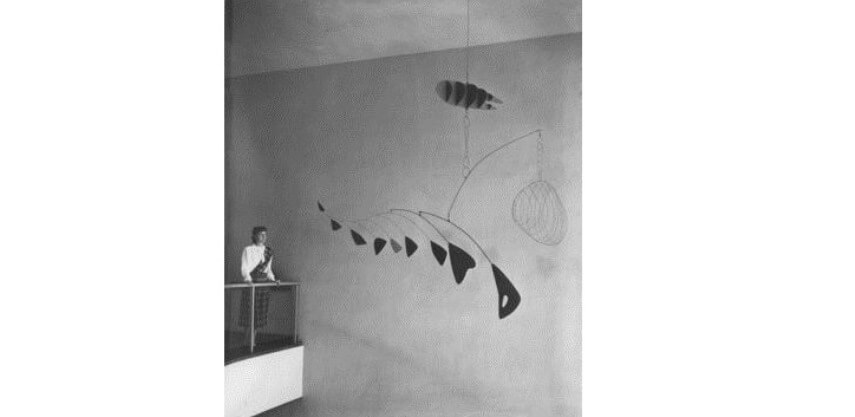

Alexander Calder - Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, 1939. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York

Drawing in Space

Over the years, Calder performed his circus all over the world in peoples’ homes, in art galleries and in museums. Many of the 20th Century’s most important artists and collectors witnessed performances of Cirque Calder. But while he was engaged in these whimsical performances, he was also thinking profoundly about the importance of the work he was doing, especially the sculptures he was making out of wire. After a decade of drawing classes he had come to see that by using thin strands of wire as a sculptural medium, he was adding the concept of line to sculpture, a revolutionary act that he called “drawing in space.”

He also recognized the importance of the fact that his wire sculptures were mostly transparent, which allowed other objects and environments around and behind them to also remain visible. About this phenomena Calder said, “There is one thing, in particular, which connects [my wire sculptures] with history. One of the canons of the futuristic painters, as propounded by Modigliani, was that objects behind other objects should not be lost to view, but should be shown through the others by making the latter transparent. The wire sculpture accomplishes this in a most decided manner.”

Alexander Calder at work in his studio, 1941. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York

Alexander Calder’s Mobiles

In 1929, Calder paid a visit to the studio of the abstract painter Piet Mondrian. Mondrian’s brightly colored geometric abstract forms impressed him, and, according to Calder, he suggested to Mondrian “that perhaps it would be fun to make these rectangles oscillate.” But Mondrian, who was not at all whimsical about his work, replied quite seriously, “No, it is not necessary, my painting is already very fast.”

Calder, however, was inspired. He became convinced that abstraction was where he wanted to focus his attention, and that movement was the next important step for sculpture to take. He began making abstract wire sculptures, using a mixture of natural and geometric forms, and he incorporated motors into these abstract sculptures in order to make them move. One day, the artist Marcel Duchamp visited Calder’s studio and Calder asked him what he should call his new kinetic sculptures. Duchamp suggested the name “mobiles,” which in French had a double meaning that implied both movement and motive. Later, the artist Jean Arp, unimpressed with Duchamp’s moniker, remarked sarcastically to Calder, “Well, what were those things you did last year—stabiles?” In his typically good-natured way, Calder agreed and indeed started rederring to his static sculptures as “stabiles.”

Alexander Calder - monumental sculpture Man (a.k.a. Three Discs), stainless steel, 1967, commissioned for the Montreal Expo. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York

Nothing is Fixed

Calder soon abandoned motors and, in deference to the natural forces of the universe, began making precariously balanced mobiles that could be moved by wind, gravity, or by touch. He wrote, “Nothing at all of this is fixed. Each element able to move, to stir, to oscillate, to come and go in its relationships with the other elements in its universe. It must not be just a fleeting moment but a physical bond between the varying events in life. Not extractions, but abstractions. Abstractions that are like nothing in life except in their manner of reacting.”

After having started out making toys and mimicking the figurative elements of life, Calder had become aware of a deeper harmony that existed in the universe. He believed he could most effectively communicate his vision through simple abstract forms and the complimentary forces of stability and movement. The reach of his aesthetic was universal. His mobiles could thrill the youngest child while wowing museum-goers and critics alike. And when given opportunities later in life to translate his vision into the monumental public sculptures that today exist all over the world, he inspired people by the millions.

What exactly Calder’s work means is perhaps impossible, or at least undesirable, to put into words. It’s more enjoyable to let it affect us on a visceral, primitive level. And that’s the precise spirit from which Calder approached his oeuvre. In order to remain open and free it’s best not to try to explain everything away. As he once said to reporters while demonstrating the kinetic motion of one of his mobiles, “This has no utility and no meaning. It is simply beautiful. It has great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it would be easier to understand but it would not be worthwhile.”

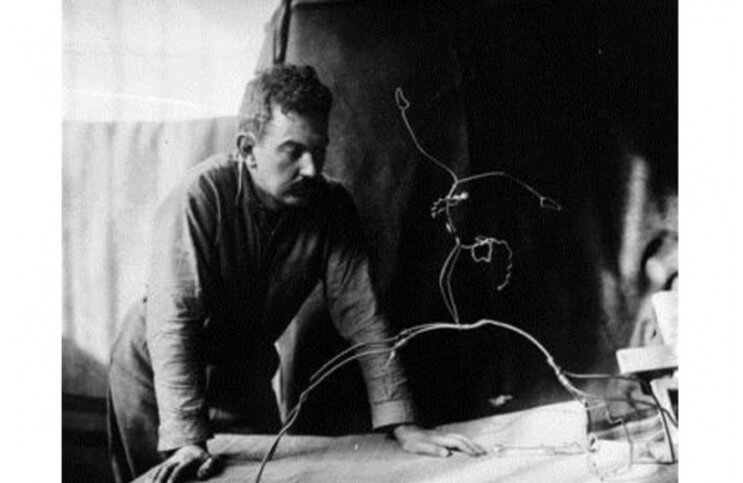

Featured Image: Alexander Calder with his wire sculpture Arching Man, 1929. © 2018 Calder Foundation, New York/Artists Right Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio