What We Need to Know About Alexander Calder Paintings

Alexander Calder is most commonly associated with the introduction of the mobile to fine art. His whimsical, kinetic sculptures sway in the slightest breeze, transforming themselves into innumerable new configurations. Less is known about the hundreds of Alexander Calder paintings, and thousand of prints, that also deservedly occupy hallowed space in important museums the world over. Calder did not consider himself much of a painter. He engaged in two-dimensional work as more of an exploratory gesture, as a way to examine ideas about color, space and composition. Nonetheless, though it may not have been his main focus, his painting oeuvre brilliantly organizes and contextualizes his ideas about movement and the relationships of objects within what he called the system of the universe.

Early Alexander Calder Paintings

Alexander Calder was born into an artistic family. His father was a sculptor, and the first artworks Calder made were in the basement studio his father maintained. Believing it would lead to a career making things, Calder studied mechanical engineering in school. But one day in 1924, while working as an engineer in the Pacific Northwest, he took notice of three snow-capped mountain peaks, and had the urge to paint them. He wrote home for paint supplies, which his mother sent. The next year he found himself in New York taking classes in painting at the Art Students League.

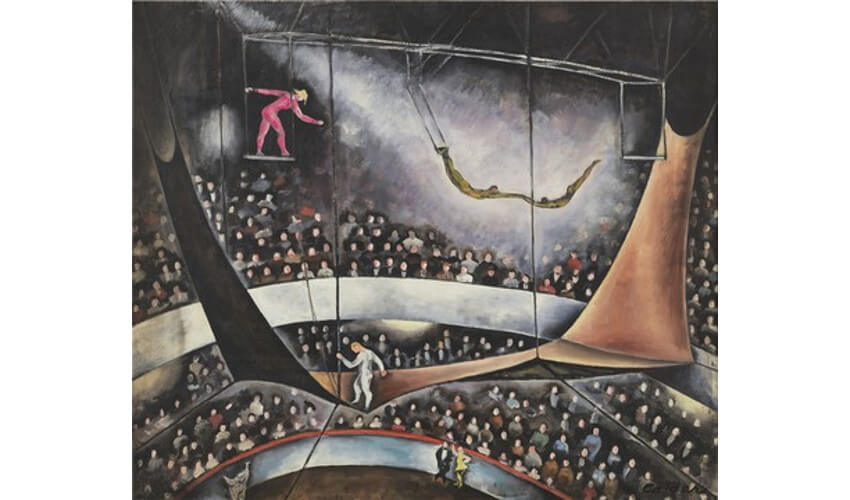

Alexander Calder - The Flying Trapeze, 1925. Oil on canvas. © Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder - The Flying Trapeze, 1925. Oil on canvas. © Alexander Calder

In class, Calder learned to paint realistic subject matter, for which he had a natural talent. He quickly earned a newspaper illustrator job. But the allure of that work was not strong enough to keep him engaged, and in 1926 he left for Paris. There, he made connections with the avant-garde artists of the time. In 1930, during a studio visit with the painter Piet Mondrian, Calder said he discovered abstraction. “I was particularly impressed by some rectangles of color he had tacked on his wall,” Calder explained. “I went home and tried to paint abstractly.”

Untitled abstract painting Calder made in 1930 after a studio visit with Mondrian. . © Alexander Calder

Untitled abstract painting Calder made in 1930 after a studio visit with Mondrian. . © Alexander Calder

Relationships in Space

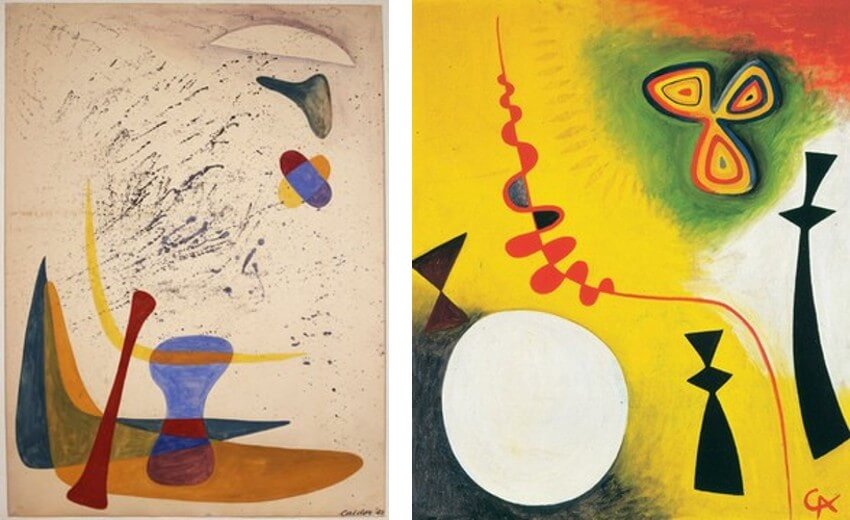

Calder quickly realized that his paintings were not achieving his desired effect, which was to create movement. So he returned to spending most of his time in the studio working in three-dimensional space. Nonetheless, he continued painting here and there, always seeking to create compositions that seemed to move. He used the entire universe for inspiration; especially the relationships bodies in space have to each other and their surroundings. He mostly limited his palette to black, white and red, commenting that if he could, he would only use red. “The secondary colors and intermediate shades serve only to confuse and muddle the distinctness and clarity,” he said.

Untitled abstract painting Calder made in 1930 after a studio visit with Mondrian. © Alexander Calder

Untitled abstract painting Calder made in 1930 after a studio visit with Mondrian. © Alexander Calder

The forms he primarily relied on in his abstract paintings were circles, spheres and discs, which, he said, “represent more than what they just are.” But he also created a unique language of shapes resembling triangles, anvils and boomerangs. He referred to those shapes as spheres, just “spheres of a different shape.” He rounded them, and attempted to give them a sense of dynamism, as if in transition. The only shape he hesitated to use was the rectangle, saying, “I don’t use rectangles––they stop. I have at times but only when I want to block, to constipate movement.”

Alexander Calder - Untitled, 1942. Gouache and ink on paper. © Alexander Calder (Left) / Alexander Calder - Fetishes, 1944. Oil on canvas. © Alexander Calder (Right)

Alexander Calder - Untitled, 1942. Gouache and ink on paper. © Alexander Calder (Left) / Alexander Calder - Fetishes, 1944. Oil on canvas. © Alexander Calder (Right)

Abstract Reality

Though most people consider his paintings abstract, Calder considered himself a realist painter. He said, “If you can imagine a thing, conjure it up in space––then you can make it, and tout de suite you’re a realist.” Nonetheless, he knew something abstract was being communicated by his work. He was aware of the limitations two-dimensional space had when it came to representing his ideas, but felt that as long as viewers were inspired to search for their own meanings he could be satisfied. He said, “That others grasp what I have in mind seems unessential, at least as long as they have something else in theirs.”

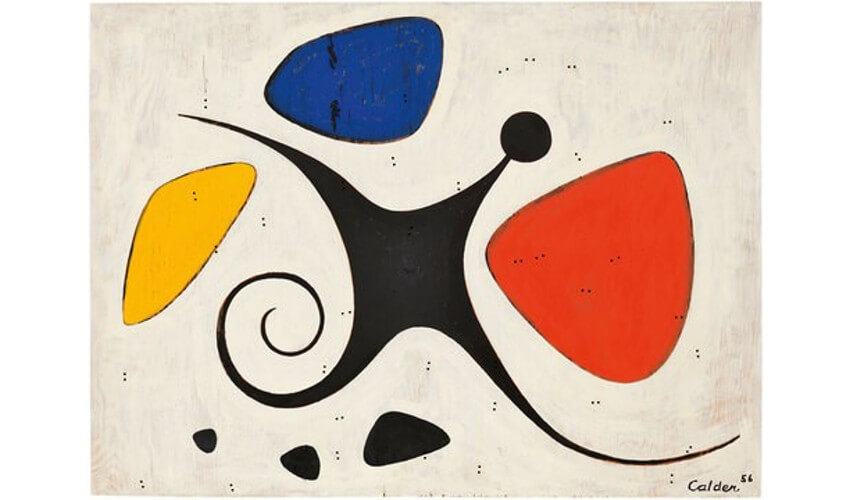

Alexander Calder - Impartial Forms, 1946. Oil on canvas. © Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder - Impartial Forms, 1946. Oil on canvas. © Alexander Calder

Throughout his career, Calder remained flexible toward his own understanding of the forms and compositions in his paintings. That flexibility is communicated well by the juxtaposition of two similar paintings he created ten years apart, the titles of which reveal the evolving relationship Calder developed toward the potentialities in his work. The first, done in 1946, is titled Impartial Forms. The second, done in 1956, contains almost the same exact language of forms, but this time the impartiality is gone. Instead the painting is titled Santos, the Spanish word for saints.

Alexander Calder - Santos, 1956. Oil on plywood. © Alexander Calder

Alexander Calder - Santos, 1956. Oil on plywood. © Alexander Calder

Featured image: Alexander Calder - Space Tunnel (detail), 1932. Watercolor and ink on paper. © Alexander Calder

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio