The Most Important Traits of Kinetic Art

What is kinetic art? The simplest definition is, “art that depends on motion for its effect.” But that is really inadequate. Scientifically speaking, everything depends on motion for its effect, since everything is moving all the time, from the largest object to the smallest particle in the universe. So maybe a better definition for kinetic art would be something like, “any purposeful aesthetic creation that, in order to be considered complete, depends on the designed, extraneous physical movement of one or more of its parts to a degree that is within the perceptible range of human senses.” But perhaps even that definition is incomplete. Maybe, as with so many other things regarding art, definitions simply fail us. Maybe instead of defining kinetic art with words we should define it with examples. With that in mind, here is a brief, admittedly incomplete examination of the history, and most famous examples, of kinetic art.

Blowing in the Wind

As with many aesthetic tendencies, kinetics manifested in prosaic creative culture far before it appeared in fine art. Probably the earliest example of artistic kinetics would be the wind chime, which was in use at least 5000 years ago throughout Southeast Asia. Yes, it would be easy to argue that wind chimes are not fine art, but then again it would also be easy to argue that they could be. Like much fine art they hint at the sacred, they explore the interconnectedness of humans and nature, and they inspire transcendent states of being. And they certainly fit the definition of aesthetic phenomena.

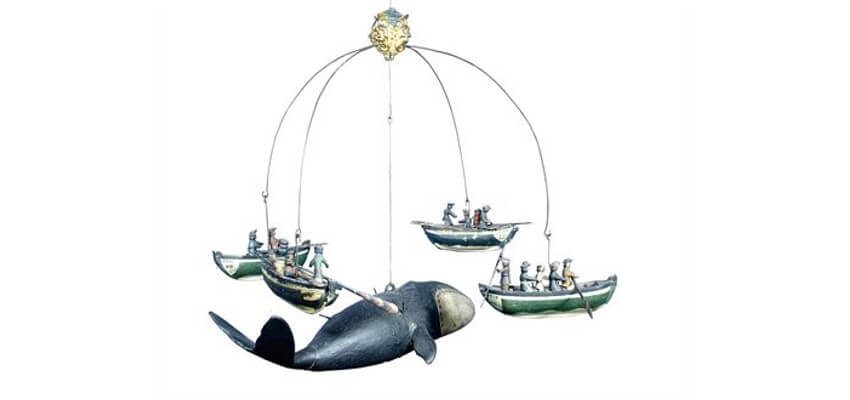

If you do not accept wind chimes as the first kinetic art, we could also turn to Nordic culture, which has a rich, ancient tradition of artistic kinetic expression. A hanging moving sculpture of a whaling voyage in the Zaans Museum in the Netherlands dates back long before the Industrial Age. And the Nordic Himmeli appear to be a direct descendent of modern day mobiles. These ancient, hanging, hand-made sculptures originated in Germanic territories (himmel is a Germanic word for sky). Though it is unclear what the original purpose of the Himmeli was, or how long they have been in use, they are kinetic, aesthetic, and they at least predate Modernism.

A centuries-old kinetic whale sculpture from the collection of the Zaans Museum

A centuries-old kinetic whale sculpture from the collection of the Zaans Museum

The First Modernist Kinetic Artist

Almost all Modernist art historians would say that the first modern kinetic artist was Marcel Duchamp, and the first kinetic artwork Duchamp made was his Bicycle Wheel. Consisting of a bicycle wheel turned upside down and inserted into the top of a stool, this artwork is also considered to be the first “readymade.” But sometimes, the more we learn about a subject, the less clear it becomes. Duchamp himself did not consider this moving sculpture to be fine art. When asked about its creation he said that he only built it because, “I enjoyed looking at it. Just as I enjoy looking at the flames dancing in the fireplace.”

If the intentions of the maker of an object are central to that object being considered fine art, by the admission of its maker Bicycle Wheel does not qualify. Who is to say that ancient wind chimes, Nordic Himmeli or a moving sculpture of a Dutch whaling voyage should not be considered kinetic art? Why should they be disregarded as crafts, toys, folk artifacts, or mere decoration? Maybe there is some hint in what Duchamp said about looking at flames in the fireplace that unites the nature of all creative phenomena, regardless of their intention, as manifestations of the some primal human urge.

Marcel Duchamp - Rotary demisphere, 1924. Yale University Art Gallery (Yale University), New Haven, CT, US. © Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp - Rotary demisphere, 1924. Yale University Art Gallery (Yale University), New Haven, CT, US. © Marcel Duchamp

The Movement Movement

What we consider to be the modern kinetic art movement really began in the 1920s. In order for an art movement to generate excitement and earn intellectual credence, it helps if someone names it and defends its position in writing. The Russian Constructivist artists Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner did that for kinetic art in 1920. Gabo and Pevsner, who were also brothers, stated in their Realistic Manifesto: “We repudiate: the millennial error inherited from Egyptian art: static rhythms seem as the sole elements of plastic creation. We proclaim a new element in plastic arts: the kinetic rhythms, which are essential forms of our perception of real time.”

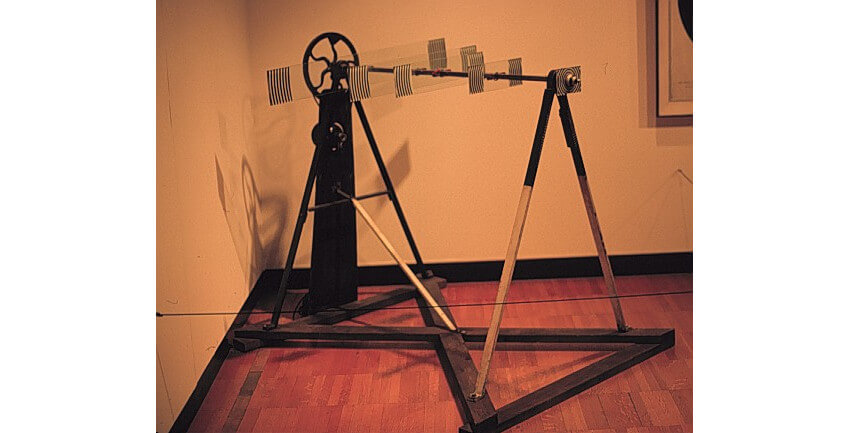

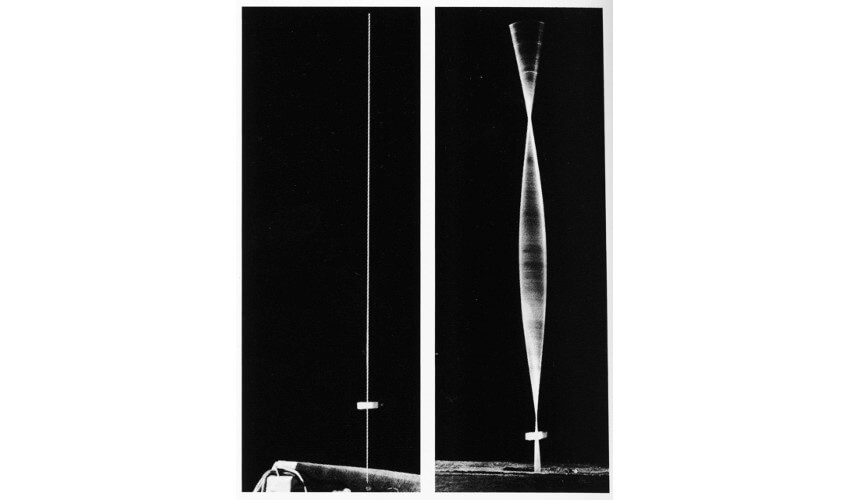

A year before writing that manifesto, Gabo, who was also a trained engineer, created what should probably be considered the first intentional kinetic sculpture. He called the piece Kinetic Construction. It consisted of a single metal rod protruding from a wooden box. When a switch was activated, a mechanical motor vibrated the rod. The piece earned the nickname “standing wave” because of the way it imitates a wave formation when activated. In addition to moving sculptures Gabo also made static sculptures that captured the aesthetics of movement, an interest he pursued throughout his career.

Naum Gabo - Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave), 1919. Metal, wood and electric motor. 616 x 241 x 190 mm. Tate Collection. © Nina & Graham Williams/Tate, London 2018

Naum Gabo - Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave), 1919. Metal, wood and electric motor. 616 x 241 x 190 mm. Tate Collection. © Nina & Graham Williams/Tate, London 2018

Upward Mobility

Around the same time Gabo and Pevsner were introducing the word kinetic into the discussion of modern art, the American Dada artist Man Ray was engaged in the creation of his own twist on kinetic aesthetics. As a friend and colleague of Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray was certainly aware of Bicycle Wheel, and he was also likely aware of Kinetic Construction. What made his efforts different from both of those works is that rather than utilizing motors or mechanisms like wheels, Man Ray sought to capture organic movement in his art.

Man Ray arrived at his solution for an organic moving sculpture in 1920 with a work he called Obstruction. It consisted of 36 hangers, each inserted through a hole drilled through the far end of the arm of another, and all hanging from a single hanger attached to a hook on the ceiling. The kinetic element of the work is introduced when the hangers are disturbed by wind, tremors or direct contact with an observer or object. In addition to building Obstruction, Man Ray created a diagram featuring instructions on how it could be replicated, encouraging anyone who attempted its replication to go beyond what he had done, and carry the sculpture on “to infinity.” This diagram is reminiscent of later conceptual artworks by artists such as Sol LeWitt, who created similar detailed instructions on how to replicate his wall drawings.

Man Ray - Obstruction, 1920. 36 interconnected hangers hanging from the ceiling. © Man Ray

Man Ray - Obstruction, 1920. 36 interconnected hangers hanging from the ceiling. © Man Ray

Rise of the Machines

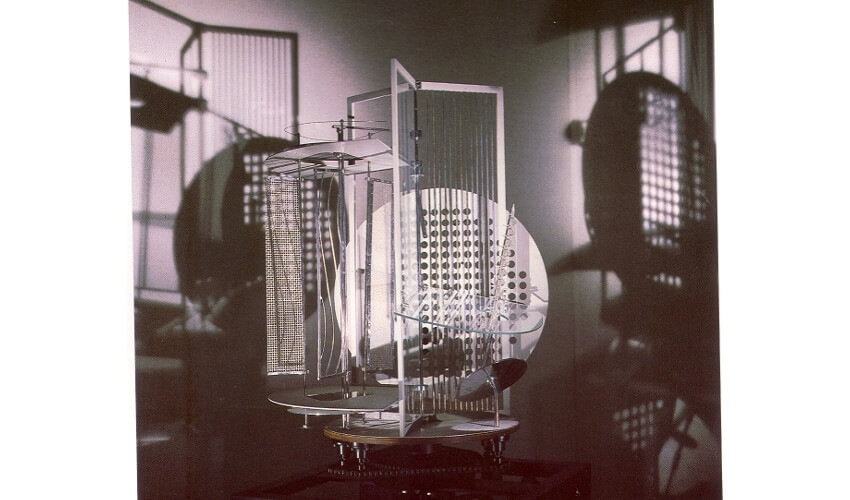

Although they were groundbreaking for their time, moving sculptures like Obstruction and Kinetic Construction almost seem quaint in comparison to what soon followed them. Throughout the 1920s, the Hungarian-born artist László Moholy-Nagy worked on a mechanical sculpture that when it was finished he called, Light Prop for an Electric Stage, or the Light Space Modulator.

This fantastical creation consisted of electric motors, moving panels and electric light bulbs in a variety of colors. When activated, it demonstrated the kinetic interplay of color, light, motion and sound. The Light Space Modulator was not only a seminal work of the kinetic art movement; it was also the beginning of the lumino kinetic art movement, and also introduced the concept of using electric light as an element of sculpture.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy - Light Prop for an Electric Stage, 1930. © Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy - Light Prop for an Electric Stage, 1930. © Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

Motion of the Masses

When many people today think about kinetic art, they visualize the whimsical mobiles of the American artist Alexander Calder. Many even consider Calder to be the father of kinetic art. But Calder did not even begin making his mobiles until 1931. As we can see, there were many others before him who were also looking to escape from the static bounds of plastic art. In fact, we cannot even talk about Calder and his mobiles without once again mentioning Marcel Duchamp who, while visiting Calder in his studio, bestowed these hanging kinetic creations with their moniker, mobiles, a word that in French could mean either motion or motive.

But Calder nonetheless widely popularized kinetic art. After Calder, the tendency has continued to be explored by generations of artists inspired by the forces of motion. Bruno Munari broke new ground in kinetic aesthetics with his Useless Machines. The American-born sculptor George Rickey created public kinetic sculptures that respond to the slightest air currents or vibrations. And the contemporary artist Emily Kennerk explores kinetics with projects such as her voice-activated vibrating dinner table, which, in the fashion of Homage to New York by the conceptual artist Jean Tinguely, uses kinetic forces to self-destruct. Though we may not be able to define precisely what kinetic art is, we can at least point to these kinetic artists and examine their work. Somewhere within their efforts we begin to see what it is about kinetic art that captures our imagination. Even if we cannot describe it we can enjoy looking at it, as Duchamp said, as we “enjoy looking at the flames dancing in the fireplace.”

Featured image: Naum Gabo - Linear Construction No. 1, 1942 - 1943. 349 x 349 x 89 mm. © Nina & Graham Williams/Tate, London 2018

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio