Defining Moments in the History of Abstract Art

Words can be so controversial. We just want to discuss the history of abstract art. But that sentence is rife with conceptual peril. (Whose history? What is art? What does it mean to be abstract?) To be precise, maybe we should title this article something like, “Defining Moments in the Chain of Events Comprising the Generally Accepted Timeline of Western Civilization Relating to Objects and Phenomena Created by Self-described Artists Not Intending to be Representational of Objective Visual Reality.” But that’s not exactly a clickable headline. (Or is it?) For the sake of sanity, for this article let’s put semantics aside and just start at the beginning.

The Pre-History of Abstract Art

Among the earliest marks of prehistoric cave dwellers were lines, scratches and handprints. Our best interpretation is that they were symbolic. So does that make them the first examples of abstract art ? Perhaps. But even the representational images left behind by our ancient ancestors aren’t exactly photo-realistic. What’s missing in our analyses is an understanding of our earliest artists’ intent. When we talk about abstract art, we mean art that was specifically intended to be abstract. Since we cannot know what prehistoric artists intended to communicate through their images, we cannot judge whether it was abstract, or even whether it’s art. It could have had utilitarian purposes for all we know. So we’ll skip ahead, way ahead, to a time better documented, when artists’ intentions were clearer.

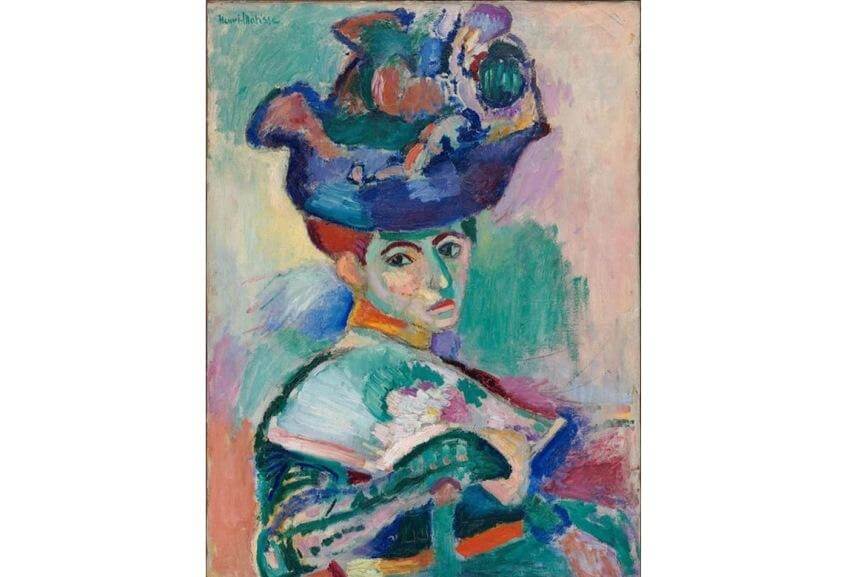

Henri Matisse - Woman with a Hat, 1905, Oil on canvas, 31 3/4 × 23 1/2 in, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Henri Matisse - Woman with a Hat, 1905, Oil on canvas, 31 3/4 × 23 1/2 in, © Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Prior to the early 1800s, it’s safe to say the vast majority of artists the vast majority of the time didn’t have the luxury of deciding what they’d make. Most pre-Romantic Era artists relied on the support of religious institutions or some other authoritarian power in order to survive. Kings and holy men therefore determined the subject matter of most of those artists’ works. As that system of patronage declined, other modes of survival presented themselves to artists. A gallery system emerged; independent art dealers began representing the work of artists; wealthy individuals and private institutions began supporting artists and collecting their works. For the first time, artists were given the chance to answer for themselves the question, “What do I want to make?” Immediately came the next inevitable question: “Why do I want to make it?” The answer to that question is a leading cause of the eventual rise of abstract art, and is perhaps the most enduring concept to emerge from the Romantic Era; one expressed by many thinkers of the time, and summed up by the French as, “L'art pour l'art.” Art for art’s sake. Or as the writer Edgar Allen Poe put it in 1850:“…would we but permit ourselves to look into our own souls we should immediately there discover that under the sun there neither exists nor can exist any work more thoroughly dignified, more supremely noble, than this very poem…written solely for the poem's sake.”

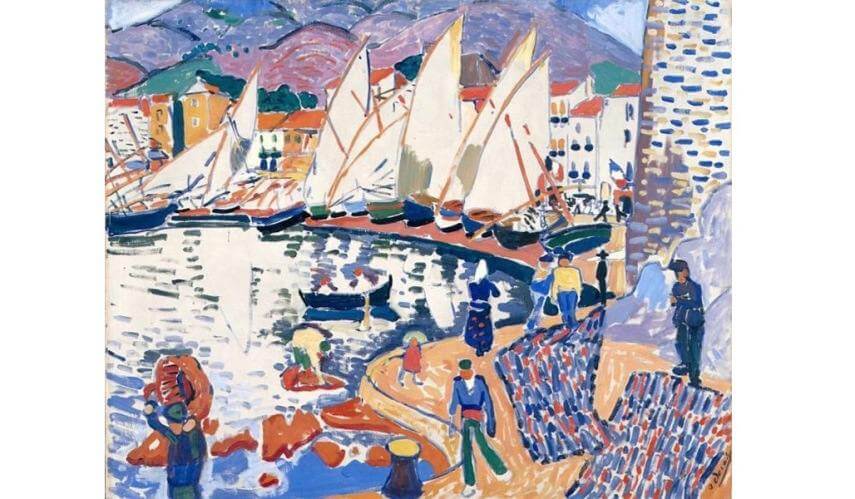

Andre Derain - The Drying Sails, 1905, oil on canvas, 82 x 101 cm, © Pushkin Museum, Moscow

First Impressions

Once artists were freed from the constraints of predetermined subject matter, they began freeing themselves of other constraints as well. From roughly the 1850s to the 1870s, the Aesthetic Movement empowered artists to make art purely for aesthetic purposes, rather than focusing on subject matter related to culture, society and politics. Then came the Impressionists, Paris-based artists who made work that focused strongly on the depiction of the qualities of light, beginning a distillation of the individual aesthetic elements of a work of art. In the 1880s, the painter Georges Seurat developed a technique of constructing an image entirely from small dots. This technique, known as Pointillism, created distorted, yet representational images. Pointillism contributed to the rise of experimental brush strokes and compositional techniques that suggested a trend toward abstraction. This trend was expanded upon throughout the Post-Impressionist period as artists began experimenting with symbolism and the arbitrary use of color, form and line.;

It’s All Subjective

In the 1900s, the Expressionists contributed the trend toward pure abstraction with their focus on subjectivity. By dramatically distorting their images, they sought to present a deeply personal point of view, representative more of emotion than of physical reality. During this period also came the rise of the Fauvists, painters focused almost exclusively on vivid color and painterly mark making. To the Fauvists, subject matter was secondary to the aesthetic components of the work. By this time, the emergence of pure abstraction was inevitable. Everywhere artists were working with symbolic representations of reality, striving to communicate ideas and feelings in ways unrelated to subject matter. They were by definition abstracting. But who was the first to succeed in making a painting that was purely abstract?

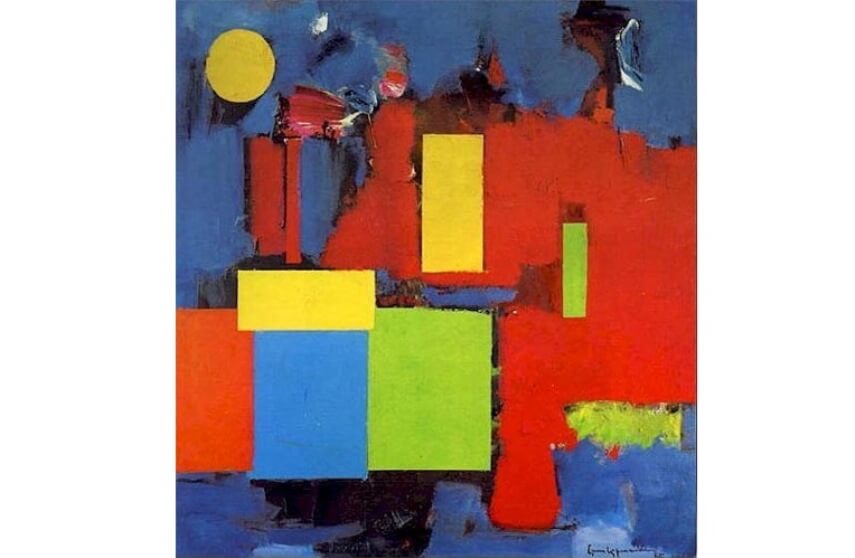

Hans Hofmann - Rising Moon, 1965, Oil on canvas, Private Collection, Art Resource, NY / Hofmann, Hans (1880-1966) © ARS, NY

Hans Hofmann - Rising Moon, 1965, Oil on canvas, Private Collection, Art Resource, NY / Hofmann, Hans (1880-1966) © ARS, NY

Will the Real First Abstractor Please Stand Up?

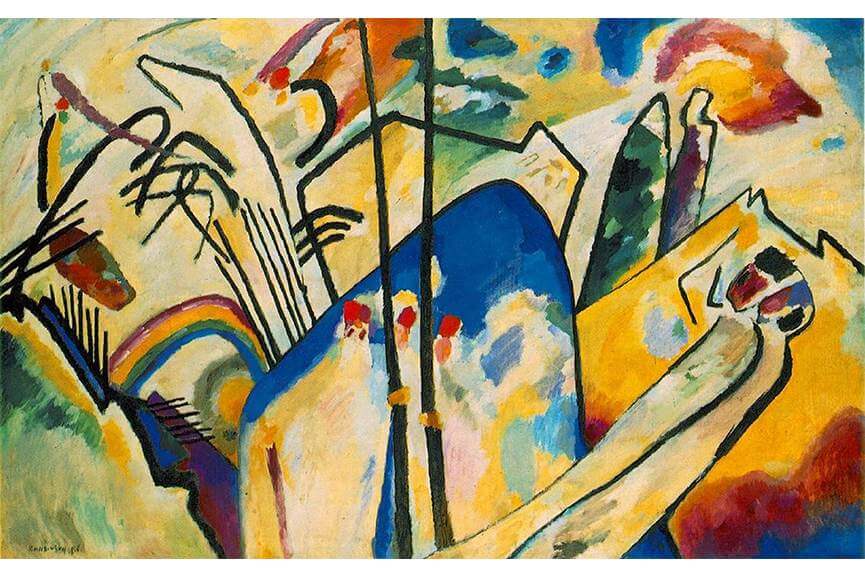

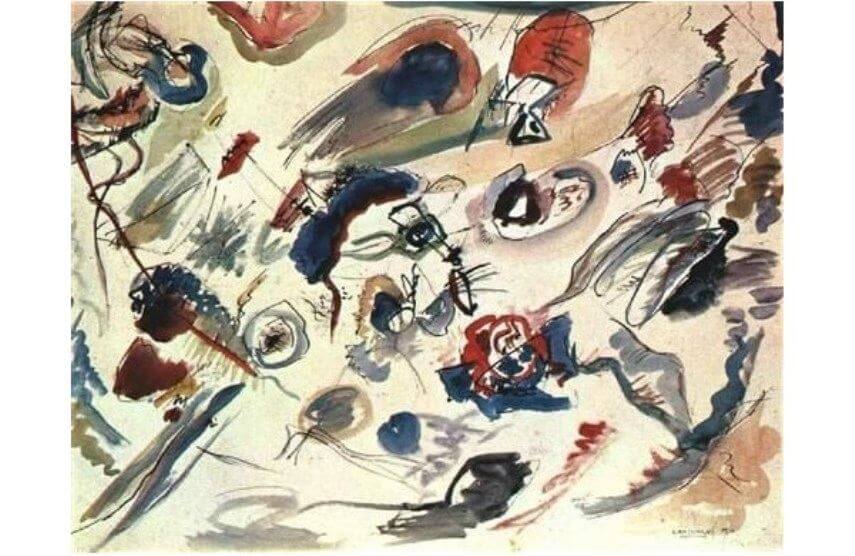

Almost all historians agree that the first abstract painting was Wassily Kandinsky’s Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor),painted in 1910. Consisting of vibrantly colored splotches, circles, lines, squiggles and color fields assembled in a seemingly haphazard way, the work in no way references pre-existing visual elements of the physical world. Conspiratorially, we could, just for fun, postulate that Kandinsky’s Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor) was not the first purely abstract painting. A year earlier, in 1909, the French avant-garde painter Francis Picabia painted Caoutchouc, a proto-cubist work featuring unrecognizable geometric shapes enveloped in seemingly unrelated color fields. This work seems in no way to represent objective visual reality. However, the word Caoutchouc loosely means natural rubber sap, a reference to the raw material for making vulcanized rubber. Having never analyzed the visual elements of unvulcanized rubber, we can’t say, but maybe this painting is representational. Who knows? What we do know is that Kandinsky was an avid art theorist and prolific art writer. He wrote enthusiastically about his pursuit to create the world’s first purely abstract work of art. He talked openly of both his intention of becoming the founder of abstract art, and his success in achieving it. No one can deny it was his intention to be the first, regardless of whether anyone predating him accidentally beat him to the punch.

Hans Hofmann - Veluti in Speculum, 1962, Oil on canvas, 85 1/4 x 73 1/2 in (216.5 x 186.7 cm), © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Hans Hofmann - Veluti in Speculum, 1962, Oil on canvas, 85 1/4 x 73 1/2 in (216.5 x 186.7 cm), © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

What Kandinsky Definitely Did

By openly announcing his intent to make pure abstract art, Kandinsky freed artists from their dependence upon references to the observable world. He divorced art from its former logic. He opened up the field to profound and rapid experimentation. He brought to its maturity the promise of the Romantics, that, as Caspar David Friedrich, the German Romantic artist said, “The Artist’s feeling is his law.”

Wassilly Kandinsky - Composition IV, 1911, oil on canvas, 250.5 x 159.5 cm, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany

The World at War

Throughout the following decades, artists experimented wildly with abstraction. Many new styles came into existence, influenced by abstraction’s call to freedom, and also by the horrors of World War I and the rise of the mechanical age. Cubism influenced artists to reduce their visual language to its most basic building blocks. Futurism demonstrated the vitality and power in the line. Dadaism challenged the meaning of art, reasserting art’s freedom from and rejection of the bourgeois. In the 1920s, Surrealism opened artists’ minds to the power of the subconscious. With its focus on dreamlike imagery and its rejection of conscious logic, it profoundly influenced abstract artists to experiment more with techniques, mediums, and methods that might connect them more directly to their unconscious selves.

Wassiliy Kandinsky - Composition 6, 1913, Oil on canvas, 76 2/5 × 115 7/10 in, 194 × 294 cm, © Wassily Kandinsky / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Erich Lessing / Art Resource, NY

Make it New!

In the 1930s, the German-born American painter Hans Hofmann is credited with spreading to America the essential philosophies of what came to be known as Modernism, the latest iteration of the rejection of the modes and methods of the past. Himself an abstract painter, Hofmann encouraged his students from California to New York to adopt new methods of image-making, in search of ways to confront and express the anxieties and wonders of rapidly industrializing society. In 1934, the poet Ezra Pound summed up the attitude of the Modernists, with his now famous call to artists: “Make it new!” Pound was a controversial figure, ultimate moving to Italy, where he supported the leading fascist figures of World War II. Nonetheless, his enthusiastic rejection of the old took root in the minds of abstract artists, leading to powerful changes on the near horizon.

Wasilly Kandinsky - Black Spot I (detail), 1912, Oil on canvas. 39.4 × 51.2in (100.0 × 130.0 cm), The Russian Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia

A New Purity

After two world wars, a global depression, famines, atrocities and two nuclear attacks on populated cities, the extent to which the average human being was experiencing anxiety in the mid-1940s cannot be overstated. This anxiety gave rise to new and widespread interest in the relatively young field of psychoanalysis. Among the many millions of people who turned to psychoanalyses during this time was Jackson Pollock , one of the leading members of a group of artists known as the Abstract Expressionists. Pollock was exposed to psychoanalyses while in rehab. It opened his mind to the world of primeval knowledge locked up within his subconscious. Many of his contemporaries were seeking new ways of connecting to the hidden essence of their humanity, working to express raw, primal emotion through their paintings. Pollock sought hidden imagery, hoping he could connect to something deep within himself, something more pure than had yet been expressed by abstract art. Around 1947, Pollock pioneered his now iconic drip technique. This technique involved the application of paint to a surface using forces such as gravity and momentum, rather than through direct contact with tools to a canvas. Embracing this new level of physicality, and utterly rejecting all sense of recognizable form, Pollock entered a new realm of pure abstraction based entirely on subconscious intent, color, movement, power and force.

Wassily Kandinsky - Kandinsky's first abstract watercolor, 1910, Watercolor and Indian ink and pencil on paper, 19.5 × 25.5in, (49.6 × 64.8 cm), Paris, Centre Georges Pompidou

The End of the Beginning

Pollock’s work in many ways fulfilled the promise of abstraction: the total freeing of the artist from the constraints of aesthetic expectation. Perhaps also, his efforts led to abstraction’s logical end. Pollock brought into sharp focus the importance of texture, materiality, process and the idea of seeing an artwork not as a surface on which to convey art, but as itself a unified form. Though reflected in a primal sense in Pollock’s work, these concepts are integral to the work of the Minimalists , who would replace the abstract expressionists as the most influential artists of the 1960s. As was Kandinsky, the leading member of the Minimalist movement, Donald Clarence Judd, was an avid art theorist and writer. Though he rejected the Minimalist label, Judd became representative of its ideas of paring down the visual language, and purifying the concepts of form and space. Rather than rejecting recognizable visual references and objective reality, Minimalist artists like Judd, Sol LeWitt, Anne Truitt and Frank Stella focused on form, the use of vibrant and pure color, hard-edged line, minimal texture and modern materiality. Rather than abstracting reality, the Minimalists manifested the shapes, colors, forms and lines often explored in abstract art, inhabiting them in physical space in a representational way.

Jackson Pollock - Convergence, 1952, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, USA

Jackson Pollock - Convergence, 1952, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, USA

The New New

The history of abstract art is the history of artists’ quest for freedom. What that means today is that artists are free to express themselves in whatever manner they choose, exploring whatever method compels them. The beauty of today’s open-ended style is that an artist can use whatever style, medium or method works best for the realization of an idea. Though Minimalism may have sidelined abstract art in the 1970s, abstraction has returned to the forefront of many artists’ practices. Contemporary abstract painters benefit from the open-minded mentality of their predecessors. Abstraction continues to connect us to something that objective reality cannot explain; something deep within us that extends beyond visible reality.

Featured image: Wassily Kandinsky - Kandinsky's first abstract watercolor, 1910, photo via Wikipedia

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio