MoMA in Paris - Hosted by Fondation Louis Vuitton

A highly touted exhibition of modern art opened in Paris this week, and it is inspiring quite a bit of celebration. But perhaps it should inspire an equal amount of consternation as well. Being Modern: MoMA in Parisfeatures around 200 works from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Held at the Frank Gehry-designed Louis Vuitton Foundation museum, the exhibition marks the first time a substantial selection of work from MoMA has been exhibited in France. It is quite easy to list the multitude of reasons that this exhibition is being heralded as a wonderful thing for France, for MoMA, and for modern art in general. After all, the list of artist and artworks included in the show spans the entire history of the museum, from its founding in 1929 until today. It includes many of the biggest names in art from the last 100 years. So obviously any opportunity to see so many influential and famous works should be seized by everyone who can possibly make it to the venue. But just for a moment, we should also take a serious look at why the show is also causing anxiety: namely, the staggering amount of hyperbolic puffery being spread about the importance of the event. The official press materials, which have been reprinted and quoted ad nauseam by the press, repeatedly call the show a “manifesto exhibition,” and describe MoMA as being called one of the “most important museums” in the world. The show is labeled “innovative,” “comprehensive,” and “unparalleled.” Over and over again the word “mythical” even pops up. And it is that last adjective, “mythical,” that seems the most dangerous, because it is the one sentiment regarding this exhibition that cannot be dismissed as mere exaggeration. Myths are powerful. And when it comes to an exhibition of this magnitude, the myths that it both creates and maintains have the capacity to shape the global narrative about art for generations to come.

Unpack Those Adjectives

The most obviously ridiculous adjective being used to describe Being Modern: MoMA in Paris is “comprehensive.” Specifically, the press kit states that, “Being Modern: MoMA in Paris is thefirst comprehensive exhibition in France of the collection ofthe Museum of Modern Art.” But in truth, while the exhibition is indeed substantial—it features around 200 objects—the current size of the complete MoMA collection is around 200,000 objects. So this exhibition features approximately one one-thousandth of what MoMA owns. It is but a minute glimpse of the full archives. Why call it comprehensive? The answer could be because the selection committee, which included representatives of both Fondation Louis Vuitton and MoMA, believes that the minuscule number of items they chose fully represents the character and substance of the remaining 199,800 objects left behind. But is that even remotely true?

Looking over the list of artists included in MoMA in Paris, it in no way appears to be representative of the entire MoMA collection. More than 75,000 objects from that collection are archived online, so I did a quick text search on that database to look for three artists who are not included in this exhibition, but who I consider to be among the most influential modern artists ever: Louise Bourgeois, Anni Albers and Helen Frankenthaler. It turns out that MoMA possesses hundreds of works by these three artists. But strangely they are not included in this exhibition. I did another search, noting that MoMA in Paris contains work by a handful of male Dadaists. So I checked to see if the MoMA archives has any work by any of the influential female Dadaists. Turns out they have more than a dozen works by Hannah Höch and Sophie Taeuber Arp, but only their better known male counterparts are included in this exhibition. So can we say this exhibition is comprehensive? Hardly. What we can say is the curators handpicked work by big name artists. But that is called a blockbuster, not a comprehensive representation of history or the MoMA collection.

Bruce Nauman – Human/Need/Desire, 1983. Neon tubing and wire with glass tubing suspension frames, 7′ 10 3/8″ x 70 1/2″ x 25 3/4″ (239.8 x 179 x 65.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Emily and Jerry Spiegel, 1991 © 2017 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Bruce Nauman – Human/Need/Desire, 1983. Neon tubing and wire with glass tubing suspension frames, 7′ 10 3/8″ x 70 1/2″ x 25 3/4″ (239.8 x 179 x 65.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Emily and Jerry Spiegel, 1991 © 2017 Bruce Nauman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Difficulty with Innovation

The next adjective from the MoMA in Paris press kit that we need to unpack is “innovative.” This is a meaningful word, and one that rightfully belongs in any conversation about modern art. Innovation implies originality, creativity, experimentation, and sometimes even genius. So is that the right word to use when describing this exhibition? As we already know, the artists were not chosen because they were, or are, the most creative, the most original, the most experimental, or the biggest geniuses. With a small number of exceptions (such as including the Brazilian constructivist Lygia Clark in with the well known Minimalist white boys club of Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella), the artists were chosen largely because of name recognition, or because they fit into the existing narrative of modern art history. But this is nothing new, of course. It is the standard curatorial tactic for sweeping historical retrospectives. And that is fine. But it is not innovative. Then again, perhaps when the word innovative is being used to describe this exhibition, it references not the show itself, but the work.

If that is the case, we should expect to see the most innovative representatives of modernism included in the exhibition. To analyze whether that is the case, look at the list of Abstract Expressionists on view. Jackson Pollock is included, as is Willem de Kooning. But where are the others? Where is Louise Nevelson, easily the most innovative sculptor of that generation? Her work is at the MoMA. Why not include it here? Where is Perle Fine? Or Jay DeFeo? Or frankly, if you are going to include the work of Jackson Pollock, why not include David Alfaro Siqueiros, the famous Mexican muralist who taught the workshop in New York City (which Pollock attended) that first introduced many of the methods that Pollock used for his iconic drip and splatter paintings. Or for that mater, why notinclude Janet Sobel, the female splatter painter who also attended the worksop by Siqueiros, and whose studio Pollock visited before “innovating” his own splatter technique. Works by both Siqueiros and Sobel are in the MoMA collection. Their absence here demonstrates that this exhibition is not about innovation. It is just a reiteration of the standard half-truths that have passed themselves off as history for generations.

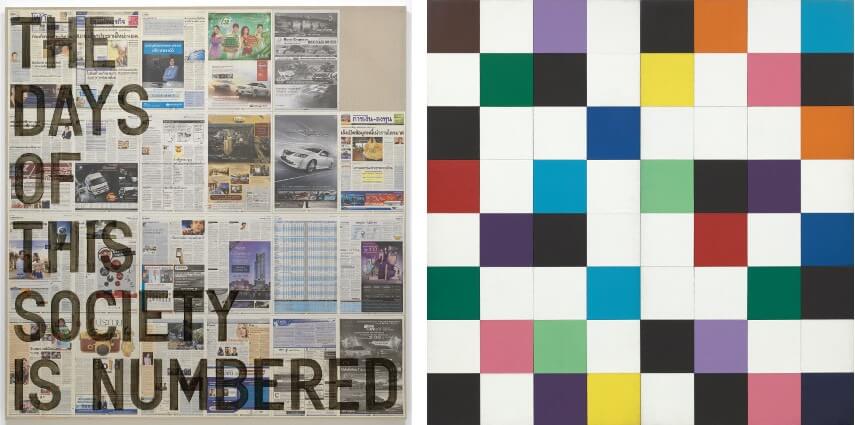

Rirkrit Tiravanija – Untitled (the days of this society is numbered / December 7, 2012), 2014. Synthetic polymer paint and newspaper on linen, 87 x 84 1/2″ (221 x 214.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Drawings and Prints Fund, 2014. © 2017 Rirkrit Tiravanija (Left) and Ellsworth Kelly – Colors for a Large Wall, 1951. Oil on canvas, sixty-four panels, 7′ 10 1/2″ x 7′ 10 1/2″ (240 x 240 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist, 1969. © 2017 Ellsworth Kelly (Right)

Rirkrit Tiravanija – Untitled (the days of this society is numbered / December 7, 2012), 2014. Synthetic polymer paint and newspaper on linen, 87 x 84 1/2″ (221 x 214.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Drawings and Prints Fund, 2014. © 2017 Rirkrit Tiravanija (Left) and Ellsworth Kelly – Colors for a Large Wall, 1951. Oil on canvas, sixty-four panels, 7′ 10 1/2″ x 7′ 10 1/2″ (240 x 240 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist, 1969. © 2017 Ellsworth Kelly (Right)

The Problem with Myths

Overall, the only adjective being used to describe MoMA in Paristhat does not stink of exaggeration is “unparalleled.” This truly is the first time so many works from MoMA have been on view at the same time in France. So okay, by definition this is unparalleled. (Though that does not mean it is not also generic.) And the only puffery-type phrasein the press kit that comes close to being true is that MoMA is one of the “most important museums” in the world. That comment is demonstrably factual. That MoMA is undeniably important can be proven in a multitude of ways. We can measure the influence the institution exerts with its acquisitions on the other major art collections in the world. After all, how many art sellers demonstrate to private collectors the importance of the artists they represent by referencing what museum collections the artist is in? (The answer is all of them.) And we can measure the number of visitors the MoMA receives each year (around two to three million). And we can look at the annual budget of the museum (around $150 million) and the salary of its director ($2.1 million in 2013). All of those metrics indicate that MoMA is indeed massively, globally influential, and therefore important.

And that brings us to the final adjective being used in conjunction with this exhibition: “mythical.” The ultimate measure of power is the ability to affect what people believe is true. MoMA is powerful. It has the power either to keep creating and promulgating myths or to set the record straight. With this exhibition, both the Fondation Louis Vuitton and MoMA have announced their intention to maintain the status quo. Yes, the works on view are full of grandeur. But how much of that grandeur has to do with authentic value, and how much has to do with the persistent marketing effort that for generations has promoted stories about art and history that are exaggerations at best, and outright lies at worst? What would truly be innovative, original, and modern would be to stage an exhibition of this magnitude that attempted to tell the truth about Modernism. Show us who Picasso copied. Show us who Pollock ripped off. Show us the indigenous artists, the female artists, the non-white artists, and the untrained artists whose necks got stepped on by the superstars we all know and love. That would be an “innovative,” “comprehensive,” and truly “unparalleled” “manifesto exhibition” I could get behind.

Featured image: Yayoi Kusama – Accumulation No. 1, 1962. Sewn stuffed fabric, paint, and chair fringe 37 x 39 x 43″ (94 x 99.1 x 109.2 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of William B. Jaffe and Evelyn A. J. Hall (by exchange), 2012. © 2017 Yayoi Kusama

All images courtesy of MoMA and Fondation Louis Vuitton

By Phillip Barcio