Becca Albee’s Innovative Way of Evoking Overlooked History

Nov 6, 2017

A traveling installation by Brooklyn-based artist Becca Albee has got me thinking about unintended connections—those misunderstandings that come from our interactions with art, some of which are inspiring, others of which are baffling. The installation is titled Prismataria, and it has so far appeared in Los Angeles, San Francisco and New York City. Basically, it occupies a single room and consists of four elements: painted walls, images hung on those walls, a rotating color-wheel ceiling light, and a custom scent filling the air. Aesthetically, it is undeniably compelling. There is a lot to look at in a small space, and much that begs to be contemplated. For example, the colors, the wall paintings, the lights and the aroma all seem abstract, and yet several of the objects hanging on the walls convey clear messages. Going in cold, one could easily get lost in contemplative bliss. But therein the baffling part of this installation lies. It is almost impossible to go into it cold. The three venues in which Prismataria has so far manifested are experimental project spaces far off the beaten path in their respective cities. That means if you know about this show and you know how to get to the space, chances are you read about it in one of the many articles that have been written about the piece online. And in every one of those articles, Albee explains the origin story behind every element of the installation. She tells the backstory on the light, the colors, the wall paintings and everything hanging on the walls. So by the time you see the show, there is no mystery, except one: what point Albee is making with the work.

Works Progress

Before we go further, please allow me a caveat: I do not believe artists have to make points, nor that art needs to have a point. The only reason I am asking what point Becca Albee is making with Prismataria is because she has gone to some lengths to explain the backstory about the work. I feel that entitles me dig deeper, because whenever artists attempt to exert this kind of control over how their work is encountered, that means they definitely have a serious point to make. So what point is Albee making? To find the answer, we should start by considering the explanations she has provided for the various elements of the show. Here is what she has said: The color, the light and the painted walls all speak to the ideas of Hilaire Hiler (1898-1966). Hiler was a painter, costume designer and color theorist who believed color was a psychological problem, not a mathematical one. He also had a gender-specific color theory that posited that women and men experience color differently. Specifically, he considered women more sensitive to color and thus more easily affected by their surroundings.

Becca Albee - arwork

Becca Albee - arwork

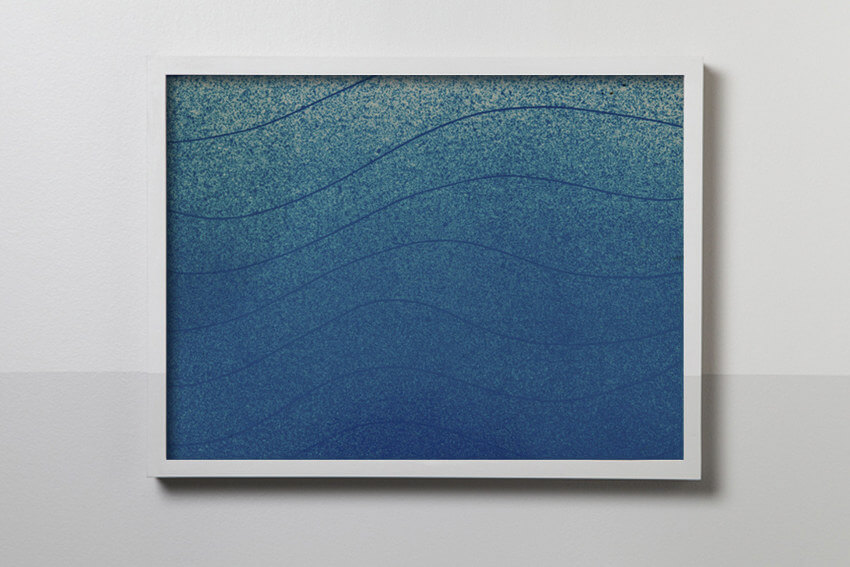

That might sound bonkers today, but during his lifetime Hiler was quite respected. During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration contracted him to design the San Francisco Maritime Museum. As part of that project, he painted two murals. One was an undersea tableau referencing Atlantis. The other was a recreation of his color wheel painted on the ceiling of a lounge intended to be used by women. That mural is called The Prismatarium. It still exists, and is the basis for the title of this installation by Albee. After seeing the mural, Albee learned that Hiler had originally planned to include a rotating color wheel light fixture for the room, but never completed it. So the light fixture in her installation is intended to be the realization of that unfulfilled plan. And the walls in Prismataria are also a nod to Hiler. They are painted gradations of grey because Hiler preached that the eye must look at grey first in order to prepare itself to properly receive color—sort of like cleansing the visual palate.

Becca Albee - arwork

Becca Albee - arwork

Radical Theories

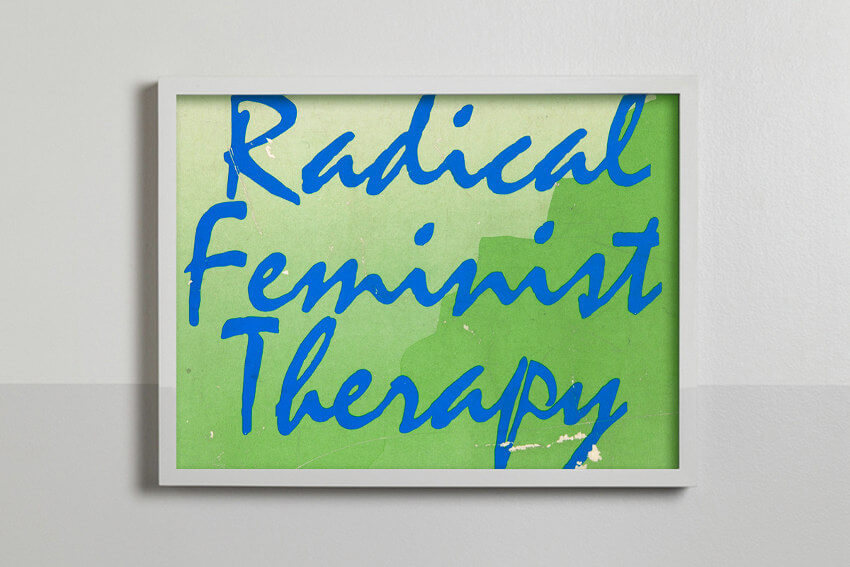

Over time, the theories Hiler professed, especially those about gender and color, were discredited as non-scientific mumbo jumbo. Which brings us to the picturesAlbee chooses to hang on the wallsin Prismataria. Some show the original Hiler mural in its decaying condition; others reference serious feminist texts, such as Radical Feminist Therapy by Canadian feminist academician and anti-psychiatry activist Bonnie Burstow; others reference the gimmicky commercial operation Color Me Beautiful, which tells women the “right colors” to use for their makeup. If I did not know anything about Hilaire Hiler and his bogus color theories, I could interpret these pictures as an abstract, conceptual conversation about identity. But since Albee has taught us about Hiler, it begs the question, “What point is she really trying to make?”

Becca Albee - arwork

Becca Albee - arwork

It seemed to me at first like Albee is honoring this man. But could that really be true? Is Albee bathing serious feminist theory in the light of pseudoscience? Is she giving it equal billing with the cosmetic industrial complex? Why? It is so baffling. But then the more I thought about this work and its ramifications, the more I realized that its baffling nature is the point. Albee is finishing the work of a fraudulent misogynist then using that work as a pretext to fetishize vanity while simultaneously diminishing the value of progressive philosophy. She is not doing it to be conceptual. That is an accurate description of how it often feels to be a woman. Women are coerced by invisible forces like history into propping up the accomplishments of unreliable men, while struggling in a confined social space to as certain whether they should resist public expectations or give in to them. Prismataria only feels baffling if you look at it like it is abstract. If you look at it like it is an image of the real world, it makes perfect sense.

Becca Albee - arwork

Becca Albee - arwork

Featured image: Becca Albee - Prismataria, 2-17, installation shot, image © Becca Albee, courtesy beccaalbee.com

All image © the artist

By Philip Barcio