Boundless Energy - The Art of Julio Le Parc

The world has rediscovered Julio Le Parc. The Argentinian-born, France-based artist, who is still active in his studio today in his late 80s, helped define kinetic art in the 1960s and was an early advocate for the idea of art as an interactive, democratic experience. But compared to his contemporaries, Le Parc has not exactly gotten his due respect. That is partially his own choice. Back in 1966, he won the Grand Prize in Painting at the 33rd Venice Biennale. Shortly afterward, he was offered a retrospective exhibition at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris. However, according to legend, he let the flip of a coin decide that he should decline the opportunity. That story illustrates his disregard for the art establishment, and his belief that art should first and foremost be for the people. It also largely explains why, despite continuing to make work, or as he calls it, conducting “research enquiries,” he fell into obscurity in the 1970s. In 2013, Le Parc resurfaced with a solo exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. To most people who saw that show, Le Parc was a revelation. The following year, he was given his first major solo exhibition in the UK, at Serpentine Gallery. Then in 2016, hefinally enjoyed his first ever retrospective museum exhibition, at Perez Art Museum Miami. This year so far his work has been featured in a major solo exhibition in New York, and is currently included in two other major exhibitions: a group show with Jesús Rafael Soto at the Palm Springs Art Museum titled Kinesthesia: Latin American Kinetic Art, 1954-1969; and a solo show at Perrotin Paris. And next month another museum retrospective of his work will open at the Tomie Ohtake Institute in São Paulo, Brazil. That show will mark an important historical moment for this artist who left South America for fear he was too revolutionary, but who now returns as a recognized pioneer who grasped more than half a century ago the social and political undertones of abstract art.

Socio-Political Roots

The artworks Julio Le Parc makes are revolutionary. Some are literally so, meaning they are constructed from pieces of reflective metal that revolve as they dangle from threads hanging from the ceiling. But his oeuvre is revolutionary in another sense as well, as it is a statement of independence and liberty. Le Parc was born in the working class city of Mendoza, which is located at the foot of the Andes Mountains, about 1100km (600 miles) from the Argentinian capital of Buenos Aires. Like most everyone else in his hometown at that time, Le Parc started working young. From age 13 to age 18 he had many jobs, including newspaper delivery boy, bicycle repairman, fruit packer, leather-smith, library employee and metal plant worker.

But he had two other interests as a young child as well. He was good at drawing pictures of celerities, and he was interested in the student protests that were occurring as young people were looking for ways to reform authoritarian elements in the government. As early as age 15, Le Parc found a way to merge all three of these factors—the work ethic, the artistic talent, and the interest in social enlightenment—by taking night classes at the School of Fine Arts. It was there that he had the good fortune of being a student of Lucio Fontana, the innovative Modernist artist whose experiments with space made him one of the most important figures in the mid-20th Century global avant-garde. Fontana introduced Le Parc to the emerging, South America Neo-Concrete movement, which inspired him to look toward the future and to take an innovative approach to aesthetics.

Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

Heading to Paris

At age 18, Le Parc left school, and also left his family. For eight years he traveled the country. At age 26, he returned to Buenos Aires with a renewed enthusiasm for his future and enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts. There, he learned to make paintings, sculptures and prints, and became connected with the other young artists of his generation. Together, he and his contemporaries challenged everything from the accepted standards of art to the accepted standards of government and society. At one point, Le Parc participated in a direct political action that resulted in students occupying the three major art schools in Argentina, kicking out the directors and trying to install a student-run school government. Though ultimately that movement was quashed and Le Parc and many of his friends were arrested, it got them thinking about their future as artists.

Le Parc and his friends took a hard look at what they could achieve in Argentina, and decided the only way to truly connect with the international avant-garde was to move to Paris. Though many of his contemporaries would never have a chance to realize that dream, Le Parc won an art contest sponsored by the French Cultural Service and received a grant to move to Paris and study art. He left Argentina in 1958. After arriving in Paris he made immediate friends with several other transplants, such as Jesús Rafael Soto and Francisco Sobrino, who were kindred spirits. He also made the acquaintance of an older generation of artists, led by Victor Vasarely, whose work with kinetics and optical illusions put them at the forefront of the vanguard in the opinion of Le Parc and his friends.

Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

Social Interventions and Utopian Light

What most interested Le Parc about kinetic art is the fact that it changes constantly according to circumstances and who is looking at it. Le Parc deduced that static art has the capacity to be authoritarian, since unchanging objects demand to be considered in a formal way. He saw movement as a way to democratize the experience of looking at art. He surmised that if the work is different every time someone looks at it, no one can ever arrive at an authoritative explanation of it. Kinetic art is therefore open, democratic, and free by nature. Viewers of such artworks are not under the thumb of the academies, institutions and critics who so often behave as though they are a fascist regime controlling the way the public experiences culture.

This core realization was transformative for Le Parc. It led him to make two other major discoveries. The first was that art should be a public experience, not just an institutional one. He put this idea into action when he and his friends instigated a series of public interventions, in which they introduced kinetic aesthetic phenomena into public areas in playful ways, requiring the public to interact with the art. The second major discovery was that one of the most powerful visual forces that can change the way people see a work of art is light. That discovery led him toward a lifelong fascination with light as a kinetic element—an element he has used as an interactive component in many of his most powerful pieces.

Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

A Legacy of Openness

Today, many young artists are interested in social practice in art and are curious about the entitlement spectators claim to define their own aesthetic experience. But many do not recognize Julio Le Parc as a leader in the generation of artists who first brought these issue to the forefront of the avant-garde. As his recent exhibitions reveal, Le Parc deserves an elevated status right alongside artists like Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley, Yves Klein, Alexander Calder, Yaacov Agam, Carlos Cruz-Diez, and of course Jesús Rafael Soto and Francisco Sobrino—artists who pioneered kineticism, optics and social practice art. Le Parc has taken the simple idea of action—of forcing viewers to move and react in order to complete an experience—and turned it into a way to democratize art. His work stands as a radical alternative to the concrete absolutism so often attached to aesthetic things. It is a reminder to keep moving, to stay open, and to embrace a constant willingness to transform.

And his work is also an invitation to remember not to be so serious, and to be willing to play. He reiterated that point in a 2016 interview in the New York Times. While walking around his studio, the interviewer, Emily Nathan, found a work Le Parc made in 1965 called “Ensemble de onze mouvements-surprise” (set of eleven surprise moments). The piece, as the name implies, had eleven different elements made of different materials and activated by motors that the viewer could control. As Nathan obviously wanted to touch it, Le Parc spoke up. He said, “Go ahead and play with it.” She did, and immediately noticed that each moving part also created a sound. A symphony of action and song sprang to life. In a perfect summation of his contribution to the legacy of democratized culture, Le Parc said of the different controls, “They all make different drawings. I might see one thing in them, but every person has permission to see whatever they see.”

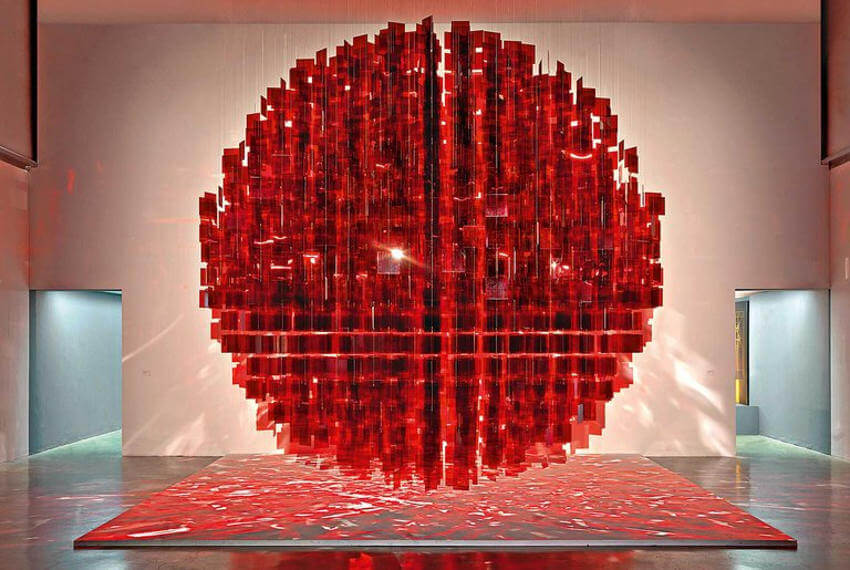

Julio Le Parc - Sphère rouge (Red Sphere), made of plexiglass and nylon. Credit Julio Le Parc © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, Photo: André Morin

Julio Le Parc - Sphère rouge (Red Sphere), made of plexiglass and nylon. Credit Julio Le Parc © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, Photo: André Morin

Featured image: Julio Le Parc - Bifurcations, solo show at Perrotin, Paris, installation view, © Perrotin

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio