Fifty Years of Pioneering Art in India - Nalini Malani at Centre Pompidou

A new exhibition at Centre Pompidou, Nalini Malani: The rebellion of the dead, retrospective 1969-2018, offers viewers a comprehensive glimpse at the work of an artist who, perhaps more than any other person on this planet, has the knowledge, wisdom and aesthetic prowess to help us deal with the unique challenges of our time. Humanity has always been divided in its goals and agendas. But today the human race is split not just over things like what language we should speak, where we should live, what we should wear and what we should eat, but over existential fundamentals—over what is true, what is real, what is meaningful, what is important, what is ethical, and what is possible. We tell competing versions of the past and harbor competing visions for the future. But some of us want an alternative path: one that is unified, equitable and free. Enter the work of Nalini Malani. This Indian artist inhabits a unique space in the contemporary art world. Like all of us she is split. Her family roots are divided between modern day Pakistan and India. She has benefited from history, yet feels duty-bound to reveal and expunge its sins. She is respected by her government, yet also feared and despised by many as a revolutionary. She is beloved by art institutions, yet also opposed to the insidious practices of most institutions. And she is also aesthetically split. She uses a visual language rife with figuration and narrative references, and yet it is the abstract elements in her work—the tones, colors, pacing, atmosphere, motion and light—that infuse it with its drama and open it up to myriad interpretations. In short, Malani is complicated, brilliant and well informed. What makes her so perfect for our time is that she is also brave enough to offer an alternative. She is adamant that the patriarchal ways of the past have brought humanity to the brink of collapse, and that if we want to survive we have got to try something new.

Separated at Birth

Nalini Malani was born to Hindu parents in the city of Karachi in February of 1946. It matters what religion her family practiced because almost exactly a year and a half later the Partition of India occurred, separating the Republic of India from the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. Fundamental to the Partition was that all Islamic residents were encouraged to leave their homes and move to what was becoming Pakistani territory, and all non-Islamic residents were expected to leave their homes and move to what was becoming Indian territory. Karachi was on the Pakistan side. So when Malani was just one year old, her parents abandoned all of their belongings and, like roughly 12 million of their fellow citizens, became refugees, starting over unemployed and in complete poverty.

In theory, the partition was a solution to social problems. It was part of the Indian Independence Act, which liberated the country from British rule. But it played into long simmering resentments between religious groups. The very idea of separating India and Pakistan according to religious affiliations failed to take into account the fact that all over the country there were numerous ethnic groups representing multiple religious points of view, many of whom spoke different languages. Violence plagued the Partition and affected all religious groups, ethnic groups and cultures. By some estimates, that violence took more than two million human lives.

Portrait of Nalini Malani in her Bombay studio, Photo © Rafeeq Ellias

Portrait of Nalini Malani in her Bombay studio, Photo © Rafeeq Ellias

Outside Exposure

After years of struggle in their new home the Malani family rebuilt their life, and thanks to the job her father secured with Air India, Nalini was able to travel to other countries for free. She recalls Tokyo being particularly memorable, as were her experiences visiting the great museums of Paris. At age 18, she was able to enroll in the Sir J.J. School of Art, a highly respected art academy named for controversial businessman Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy who made his fortune in the 19th Century Chinese opium trade. While a student there, Malani also acquired a studio space off-campus within a multi-disciplinary artistic environment called the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute, named for Bhulabhai Desai, an influential and controversial political activist.

It was there at the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute that Malani learned the value of collaboration, as she was able to work with singers, dancers, actors, theatrical writers, photographers and filmmakers. The experience showed her that theater and film are the most holistic mediums, since they incorporate so many other aesthetic methods, such as painting, design, sculpture and performance. That realization transformed her personal artistic practice, expanding her work beyond the boundaries of the canvas. As her current retrospective demonstrates, she has become spectacularly innovative in combining multiple elements to create aesthetic deluges in which viewers literally become immersed.

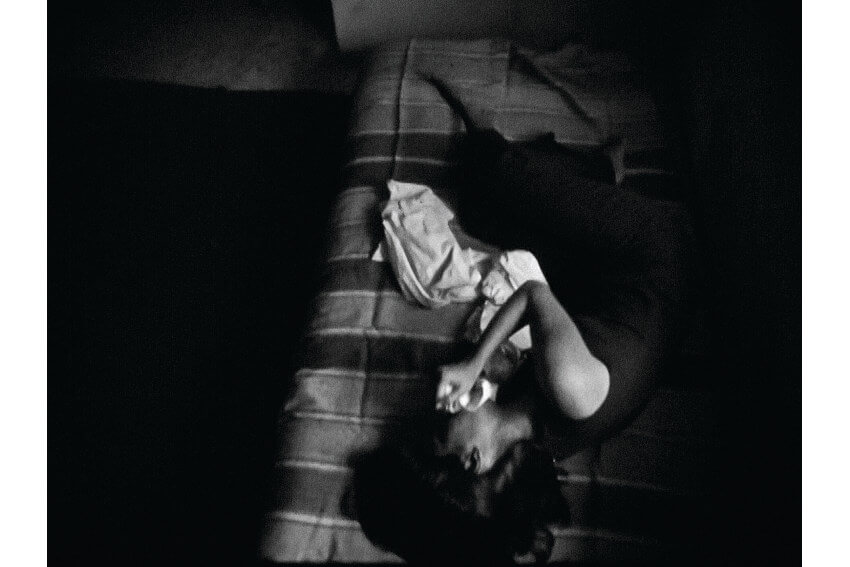

Nalini Malani - Onanism, 1969, Black and white 16 mm film transferred on digital medium, 03:52 min. Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Photo © Nalini Malani

Nalini Malani - Onanism, 1969, Black and white 16 mm film transferred on digital medium, 03:52 min. Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Photo © Nalini Malani

A Complicated Past

Much of the content Malani works with is interpreted figuratively. Herart is called feminist because it presents female imagery in ways that imply empowerment. It is called anti-war because it presents imagery of violence in ways that evoke horror and death. It is called anti-colonial because it often includes text that addresses the exploitation of the third world by first world powers. In fact, the subtitle of the current retrospective at Centre Pompidou, The rebellion of the dead, takes its title from the Heiner Müller play The Order. In that play, the character Sasportas, an allegorical representative of the Third World, gives a speech presaging an oncoming revolution of the oppressed, to wit, “When the living can no longer fight, the dead will. With every heartbeat of the revolution flesh grows back on their bones, blood in their veins, life in heir death. The rebellion of the dead will be the war of the landscapes, our weapons the forests, the mountains, the oceans, the deserts of the world. I will be the forest, mountain, ocean desert. I—that is Africa. I—that is Asia. The two Americas—that is I.”

Malani has often appropriated segments of that quote, such as in a body of prints she created in 2015. The sentiment behind it is that the rulers of the past have caused nothing but death, which has bred a longing for revenge, and which in return will give way to even more violence and more death. This is a sentiment Malani knows much about. She was born into a world full of violence and contradictions, and trained to be an artist in one. She is aware of both the sins of the past and the opportunities they afford us in the present. Her work turns this complicated reality into fodder for imagination. But it is not explicit, but rather suggestive. For example, hovering in the background of all of the images that take their names from the above quote are the faces of soulful, empowered, empathic women. The meaning is abstract, but these faces seem to be harbingers of a new day.

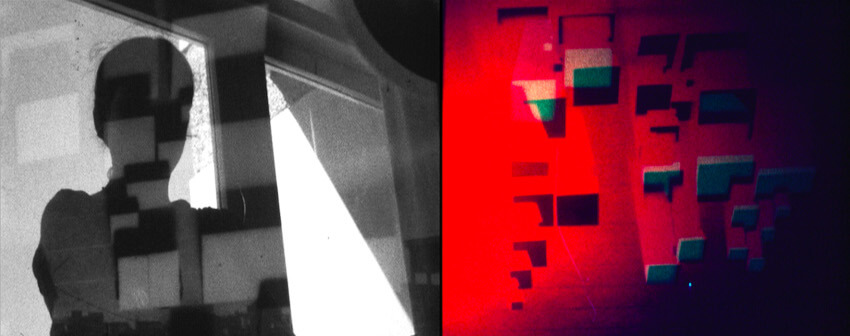

Nalini Malani - Utopia, 1969-1976, 16 mm black and white film and 8 mm colour stop-motion animation film, transferred on digital medium, double video projection, 3:49 min, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Photo © Nalini Malani

Nalini Malani - Utopia, 1969-1976, 16 mm black and white film and 8 mm colour stop-motion animation film, transferred on digital medium, double video projection, 3:49 min, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Photo © Nalini Malani

A Feminine Future

The new day Nalini Malani strives for is one in which the feminine side of human nature will become more influential. As she said in her interview with Sophie Duplaix, curator at Centre Pompidou, “Over the years, women in selective societies have acquired a degree of equality with men, but still today there is too much left wanting. For me understanding the world from a feminist perspective is an essential device for a more hopeful future, if we want to achieve something like human progress. It is clear that we have followed for too long a linear patriarchy that is coming to an end, but stubbornly wants to assert, 'it is still the only way.' Or, if I wanted to state it more dramatically, I think that we desperately need to replace the alpha male with matriarchal societies, if humankind wants to survive the twenty-first century.”

Malani is a living representation of this hope. She was the first female artist to receive the Fukuoka Asian Art Prize, and she also organized the first ever all female art exhibition in India. But perhaps her most hopeful act was in the 1970s when she studied art in Paris for three years. She was given the opportunity to stay and build a successful career based in Europe. But she declined. Despite all of the pain and complications of her life in the new country of India, she dedicated herself to its future. She believed she had the power to be a force for positive change, and ever since she has lived that belief through action. The work that has come out of her decision is a beacon for all who long for a less divisive world and a more equitable future, not only for India but for the human race. Nalini Malani: The rebellion of the dead, retrospective 1969-2018 is on at Centre Pompidou through 8 January 2018 after which it travels to Castello di Rivoli, near Turin, Italy, from 27 March through 22 July 2018.

Nalini Malani - Remembering Mad Meg, 2007-2011, Three-channel video/shadow play, sixteen light projections, eight reverse painted rotating Lexan cylinders, sound, Variable dimensions for the installation, Exhibition view of Paris-Delhi-Bombay, Centre Pompidou, 2011, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Photo © Payal Kapadia

Nalini Malani - Remembering Mad Meg, 2007-2011, Three-channel video/shadow play, sixteen light projections, eight reverse painted rotating Lexan cylinders, sound, Variable dimensions for the installation, Exhibition view of Paris-Delhi-Bombay, Centre Pompidou, 2011, Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris, Photo © Payal Kapadia

Featured image: Nalini Malani - All We Imagine as Light, 2016, Six reverse painted tondi (detail : I am Everything You Lost, 2016), Ø 122 cm, Arario Museum, Seoul, Photo : © Anil Rane

All images courtesy Centre Pompidou, Paris

By Phillip Barcio