Developing the Optical Abstraction or How Victor Vasarely Found His Own Style

It is sometimes assumed that when we talk about “arts and sciences” we are talking about distinctly different things. Science is about studying things, after all, whereas art is about creating things. But don’t scientists also create and artists also study? And isn’t imagination integral to both? Victor Vasarely was both a scientist and an artist. The father of a Modernist abstract art movement known as Op-Art, he comfortably inhabited both worlds. Initially trained in medicine, Vasarely approached art from a systematic perspective. He analyzed the formal qualities of what constituted an aesthetic object. He studied nature in search of the building blocks of the visual universe. And he analyzed the way viewers perceived the visual universe in search of how art could help reveal fundamental truths. From the 1920s when he conducted his earliest aesthetic experiments, through the 1960s when he revealed his ultimate creation, the “Alphabet Plastique,” till the end of his life at age 90, Vasarely approached his art from a viewpoint that simultaneously included creativity and analyses. Along the way he altered how humans view two-dimensional space and created a body of work that even decades after his death continues to inspire artists, art lovers, designers and scientists alike.

Victor Vasarely the Scientist

In 1906, when Victor Vasarely was born, artists and scientists were equally respected. In Budapest, where Vasarely went to university, it wouldn’t have been unusual for members of both fields to interact with each other, especially in the bustling cafés along the banks of the Danube, which were centers of the European intellectual scene. When Vasarely first entered university, it was to study to become a doctor at the University of Budapest’s School of Medicine. But two years in to the program he abruptly changed direction and decided to devote himself to studying art.

But though his subject matter changed, his approach to learning did not. In 1927, at the age of 21, Vasarely enrolled in a private art school where he received formal training as a painter. He excelled as an art student, and while honing his aesthetic skills he also continued reading books by the leading scientists at the time. One of his favorite authors to read at this time of his life was Niels Bohr, who in 1922 received the Nobel Price for his study of atomic structure. In quantum physics, the Bohr model depicts the structure of an atom as being similar to that of the structure of the solar system. Visually, it resembles a circle surrounded by larger circles, a pattern Vasarely would explore repeatedly in his art.

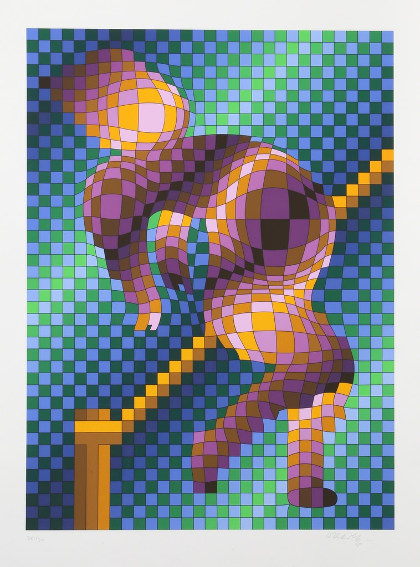

Victor Vasarely - Harlequin Sportif, ca. 1988. Screenprint. 38 1/2 × 28 1/2 in; 97.8 × 72.4 cm. Edition of 300. RoGallery. © Victor Vasarely

Building his Case

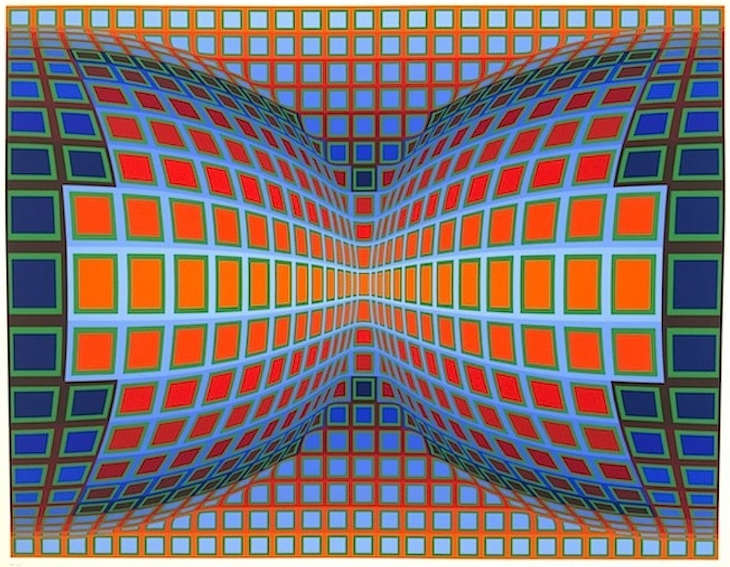

Through his dual study of art and science Vasarely began to formulate a theory that the two modes of thought intersected in a way that when perceived together could, as he said, “form an imaginary construct that is in accord with our sensibility and contemporary knowledge.” In 1929, he enrolled at Budapest’s Muhely Academy, which at the time was Hungary’s equivalent of the Bauhaus. His studies there focused on the concept of a total art based on geometry. He experimented with geometric abstraction and began to understand how optical illusions could be created through the arrangement of geometric shapes and colors on a two-dimensional surface. A comparison of one of his Muhely Academy paintings titled Etudes Bauhaus C to a painting he made in 1975 titled Vonal-Stri demonstrates Vasarely’s life-long and single-minded focus on the possibilities of geometry to express the intersection of science and art.

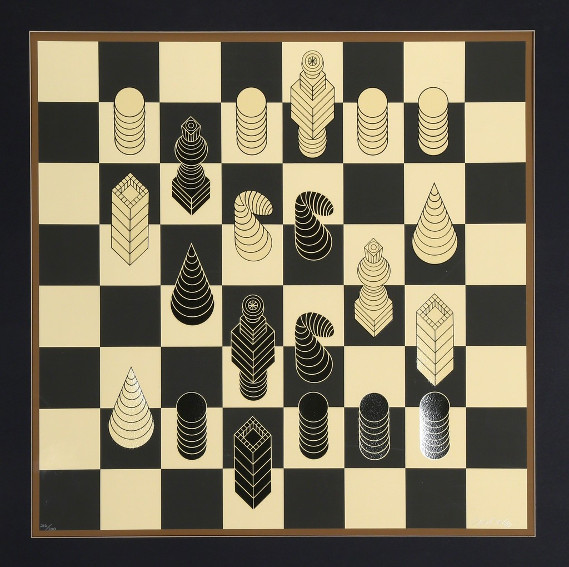

After leaving the Muhely Academy, Vasarely moved to Paris, got married and had two children. He supported his family as a graphic artist, pursuing his art at night. Whereas his day job required a clean, precise style, his art practice was open to his imagination. He developed a personal style steeped in both. It manifested in his “Zebra” and “Harlequin” paintings, series that he returned to throughout his life, and in paintings like “The Chessboard.”

Victor Vasarely - Chessboard, 1975. Silkscreen. 31 1/2 × 30 in; 80 × 76.2 cm. Edition of 300. RoGallery. © Victor Vasarely

The Wrong Path

After 14 years working on dual careers in Paris, Vasarely finally received his first major exhibition. It was well enough received that he was convinced that he could commit full time to being an artist. It was around this time that he took a departure from the visual style he had been creating. While vacationing on an island in Brittany, he took notice of the way waves affected the landscape, especially how they altered the coastline and shaped the stones. This observation led him down a path toward a sort of biomorphic geometric abstraction as he attempted to connect with a visual manifestation of the natural geometry of the organic world.

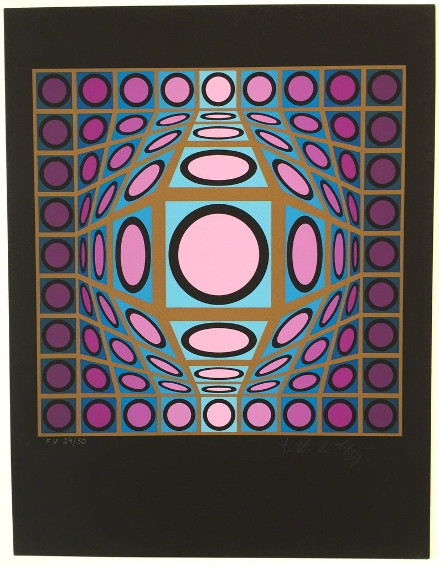

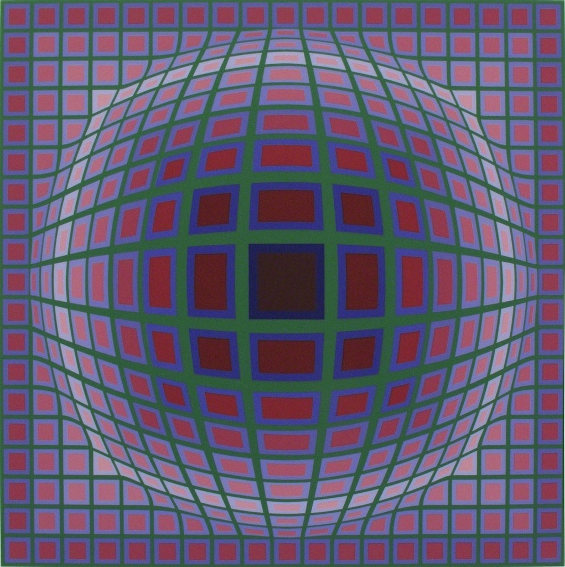

Although Vasarely later referred to this time in his life as “the wrong path,” it resulted in an important evolution in his work. It added more rounded elements to his paintings. When he returned to his previous geometric style it was with the inclusion of dynamic rounded forms that seemed to bulge outward from the painting or collapse inward from the surface. The way these forms tricked the eye it seemed as though the image was moving. That kinetic illusion, combined with the three-dimensionality of the images on Vasarely’s canvases, became the foundation for iconic aesthetic we now call Op-Art.

Victor Vasarely - Untitled #8 (pink and turquoise sphere). Screenprint. 13 × 10 in; 33 × 25.4 cm. Edition of 50. Gregg Shienbaum Fine Art. © Victor Vasarely

The Yellow Manifesto

In 1955, Vasarely exhibited some of his work in an exhibition of kinetic art called “Le Movement” in Paris. To accompany his work he published an essay called Notes for a Manifesto. Printed on yellow paper, the essay has since come to be known as The Yellow Manifesto. In it Vasarely declared, “We are at the dawn of a great age.” He insisted that labels such as painting and sculpture were outdated since artists such as Arp, Kandinsky, Mondrian and Calder had destroyed the artificial separations between the plastic arts. He declared that since all aesthetic phenomena are manifestations of the same impulse, it was time to regard all artistic achievements as part of “a single plastic sensibility in different spaces.”

Vasarely’s contribution to this “great age” is clear when looking at the paintings he made during this time in his life. His work completely redefined the viewer experience of a two-dimensional work of art. He created the perception that space existed where space did not exist. The viewer experience was transformed to exist entirely within the viewer’s mind. The forms that reside on one of Vasarely’s canvases are formal and scientific, and yet when interpreted by the eye they assume qualities that seem to defy the scientific facts of spatial reality.

Victor Vasarely - Papillon, 1981. Silkscreen on Arches paper. 30 7/8 × 37 7/8 in; 78.4 × 96.2 cm. Edition of 250. © Victor Vasarely

The Plastic Alphabet

At the height of his popularity in the 1960s, Vasarely created what would represent the culmination of his life’s work. He described what he called the Plastic Alphabet, a symbolic visual language based on geometric forms and colors. There were 15 forms in the alphabet, all based on variations of the circle, the triangle and the square, and each of the forms existed in a range of 20 different hues. Each form was portrayed within a square frame, and the shape and its surrounding frame were presented in different hues. The Plastic Alphabet could be arranged into a seemingly infinite assortment of combinations and utilized to create an evidently endless array of images.

The concept that Vasarely explicitly implied with his Plastic Alphabet was that through its implementation, the creative act could be conducted through a purely scientific process. On one hand it was dehumanizing, as it represented a form of programming, like a proto-artificial intelligence that could take over the process of making art. On the other hand it was humanizing, as it democratized and demystified the creative process, allowing anyone to engage in a creative aesthetic activity.

Victor Vasarely - Titan A, 1985. Screenprint. 22 × 23 1/2 in; 55.9 × 59.7 cm. Edition of 300. Gregg Shienbaum Fine Art. © Victor Vasarely

Art For All

It is fitting that the contribution for which Vasarely is most remembered is a form of disruption. Not only did his visual work distort the surface of two-dimensional art, but his ideas and his Plastic Alphabet also distorted the surface of the culture. Vasarely’s friends, colleagues and followers enthusiastically recall that one of his mottos was “art for all.” He was thrilled to see his art included on clothing, postcards, commercial products and advertisements. He foresaw that in the future the only way art could remain relevant was if every human being could participate in its enjoyment.

Not only can we see echoes of Vasarely’s art in the products of contemporary art and design, we also see echoes of his philosophy in the digital community and the global culture to which it has contributed. By creating a style of fine art that could have universal appeal across artificial social divisions, Vasarely created something unique: a sincere and joyful aesthetic experience that, although abstract, can easily be enjoyed by anyone who can see. And perhaps more valuable still he shared a vision of a future in which art and science work together toward a more interesting and equitable world.

Featured Image: Victor Vasarely - Zebra, 1938. 52 x 60 cm. © Victor Vasarely

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio