Remembering the Great Robert Ryman

Feb 15, 2019

The American painter Robert Ryman has died at age 88. His death was announced in a statement from his gallery. A self-taught artist, Ryman created a vast oeuvre that has intrigued, delighted, and baffled viewers for more than 50 years. The vast majority of his paintings were mostly white. Ryman was always quick to point out, however, that they were not intended to be “white paintings.” Rather, he described them as paintings on which the color white was utilized as a way to make other things become visible. He was not trying to reveal things himself. He had no social, political, or intellectual agenda. Rather, he was creating situations in which the paintings might be able to reveal themselves. White, he believed, was more revelatory than other colors. He likened the effect to spilling coffee on a white shirt. “You can see the coffee very clearly,” he said. “If you spill it on a dark shirt, you don’t see it as well.” As for the question of what things were revealed by the whiteness in his paintings, Ryman generously left that up to the viewers. He said, “What painting is, is exactly what people see.” Over the decades, people have reported seeing all kinds of things, and non-things, in his paintings. Some say they see cotton balls or cloud formations. Others report seeing conceptual expressions of the technical processes of painting. Many described what they see as abstract. Ryman, however, did not consider himself an abstract painter. He considered his paintings self-referential objects. “There is no symbolism or story that I need to tell,” he said. His soft spoken insistence on this point made him the perfect ambassador for the eternal relevance of painting. By making hundreds of beautiful paintings, while barely deviating from his use of a single color, Ryman proved undeniably that an endless variety of paintings still wait to be made.

Paintings, Not Pictures

Robert Ryman was born in Nashville, Tennessee in 1930. After graduating from college he served in the US Army as a musician, playing in an Army Reserve band during the Korean War. When he moved to New York City in 1953, he did so with the intention of becoming a jazz musician, not a painter. He had never even taken an art class before. His main ambition was just to find a job in the city with as little responsibility possible so he could focus entirely on his creative life. Ryman accepted a position as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art. It was there that he saw his first paintings. At first, he did not realize that what he was looking at were paintings, per se. He saw the things hanging on the walls of the museum as pictures. He saw their surfaces and materials as secondary to the subject matter the pictures were intended to convey.

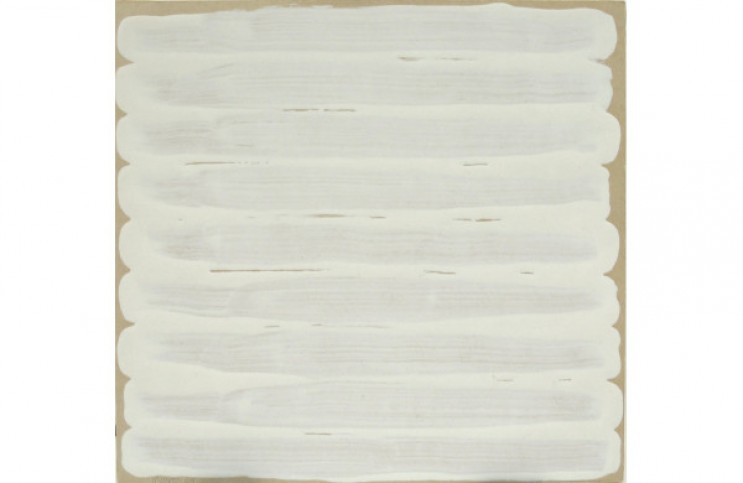

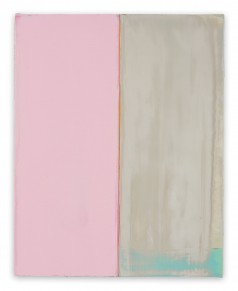

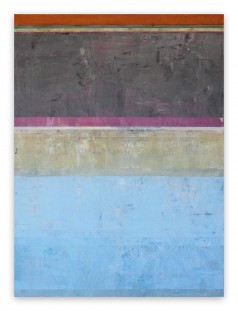

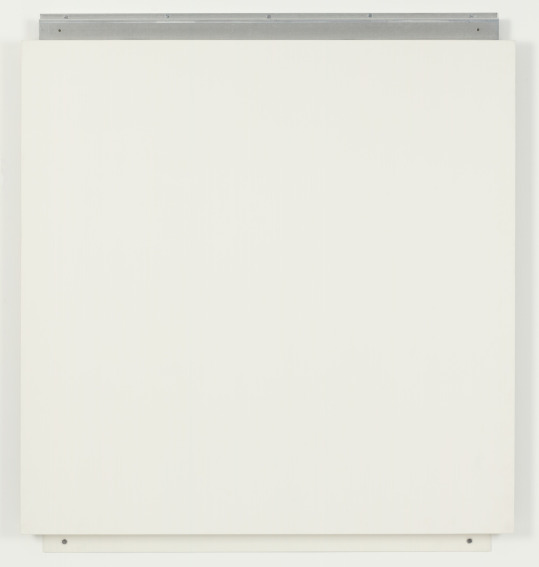

Robert Ryman - Attendant, 1984. Oil on fiberglass with aluminum, bolts and screws. 51 7/8 x 47 x 2 1/8" (131.8 x 119.4 x 5.4 cm). Anne and Sid Bass Fund. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Robert Ryman

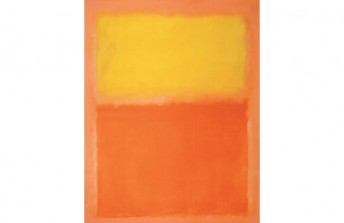

His mind changed the first time he saw a painting by Mark Rothko. Said Ryman, “I’d never seen a painting that way before. I’d been looking at pictures all the time, and here was something that had a totally different feeling to it.” Rothko did not perceive of his paintings as pictures. He considered them to be transcendental gateways. He intended the surface, the paint, the colors, the textures, the light, and the physical surroundings of the painting to all be part of the same experience. He wanted viewers not to look “at” the paintings, but to become immersed within the experience of them. Through the contemplation of his paintings, Rothko hoped viewers would enter a contemplative state—that was the real point of his work. “I did not know what he was doing,” said Ryman. But Ryman was at least aware from that point on of the essential difference between paintings and pictures. Inspired by this revelation, he headed out to the hardware store and for the first time in his life bought paints and a surface to paint on.

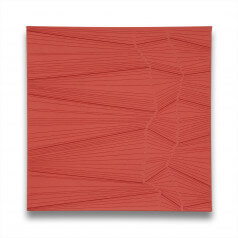

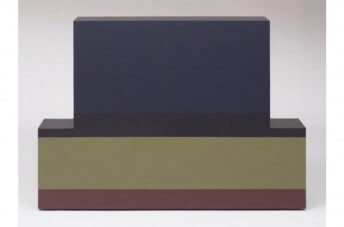

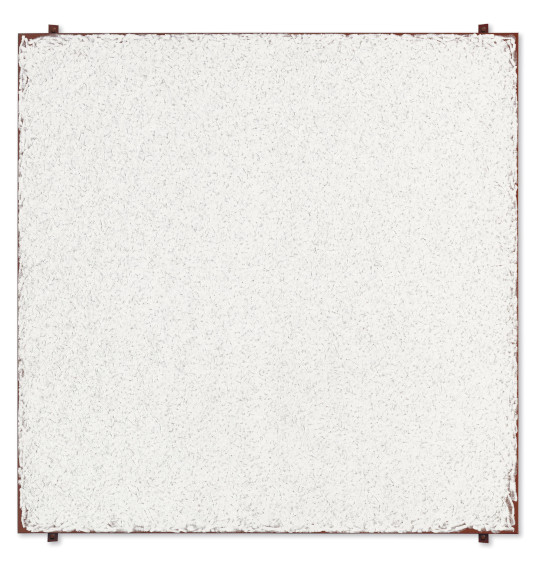

Robert Ryman - Bridge, 1980. Oil and rust preventative paint on canvas with four painted metal fasteners and square bolts. 75 1/2 x 72 in. (191.7 x 182.8 cm). Konrad Fischer, Dusseldorf, Thomas Ammann, Zurich, Acquired from the above by the present owner. © 2019 Robert Ryman

Never Stop Experimenting

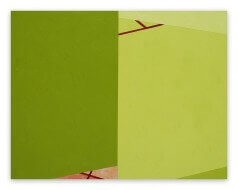

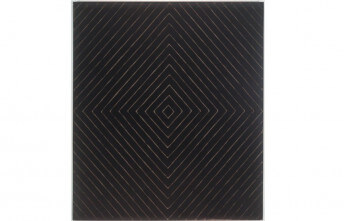

Having never participated in the academic art world, Ryman was unburdened by any biases that might have challenged his understanding of how to make a painting. He opened himself up to every possibility, and allowed himself the pleasure of simply enjoying the process of applying paint to surfaces. He fascinated himself with the feeling of his various tools, the ways they interacted with various mediums, and the ways those mediums transformed various surfaces. His first paintings were nearly monochromatic—mostly green, or orange. But the dominant color was not the only color. “Untitled (Orange Painting)” (1959) is splotched with yellows and reds and greens and blues. Orange might be the first thing a viewer sees, but soon after, the eye, and then the mind, is drawn to the contradictions in the work.

Robert Ryman - Untitled (Orange Painting), 1955 and 1959. Oil on canvas. 28 1/8 x 28 1/8" (71.4 x 71.4 cm). Fractional and promised gift of Jo Carole and Ronald S. Lauder in honor of David Rockefeller on his 100th birthday. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Robert Ryman

Those contradictions are what eventually attracted Ryman to the color white, because it provided such stark contrasts. Yet, despite relying so heavily on the color white, Ryman never lost the sense of experimentation that informed his earliest works. He was living proof of the idea that limitation breeds creativity. He stuck to white, but used dozens of mediums. He stuck to a square format, but varied the size, from paintings as small as a few inches square to one that is essentially a square wall. He found variety in the types of surfaces he painted on, and experimented with how his paintings were attached to walls. The only thing he did not vary was the circumstances in which his paintings were shown. In order for his paintings to function properly, he believed they needed to be displayed on the walls of clean, white-walled galleries with standard lighting. His exhibition traditionalism was grounded in his belief that every painting has something of its own that it wants to express. “The painting needs a certain reverent atmosphere to be complete,” Ryman once told Art21. “It has to be in a situation so it can reveal itself.”

Featured image: Robert Ryman - Untitled, 1965. Enamel on bristol board. 7 3/4 x 8 1/8" (19.7 x 20.6 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2019 Robert Ryman

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio