How to Define Monochrome Painting

In 1921, the Constructivist artist Alexander Rodchenko exhibited three monochrome paintings – titled Pure Red Color, Pure Blue Color, and Pure Yellow Color – which he deemed the ultimate pictorial statement, and declared painting was dead. If monochrome painting did kill painting then painting has died a thousand deaths. Ancient Chinese artists painted monochromes as did Hindu artists. Rodchenko wasn’t even the first modern Western artist to paint a monochrome. Kazimir Malevich’s White on White tried to kill painting three years earlier. But rather than killing painting, monochromes succeeded in exactly the opposite. They gave it new life.

Monochrome Painting’s True Colors

We learn about color through experience. Any sentient creature capable of noticing different colors is also potentially capable of associating personal thoughts and feelings with them. Thus a single color may evoke a multitude of different reactions depending on the associations various seers connect it with. Aside from being a style of painting that only uses one color, monochrome painting is a transcendental tool. It’s a way for artists to grapple with the phenomenon of color and emotion, color and spirituality, color and the mind. By focusing on a specific hue as the subject of a painting, an artist can explore the range of associations viewers have with that hue.

Many writers, theorists and artists have tried to define the conscious, subconscious, mystical or scientific qualities of the various hues that make up the world of color. But color is woefully subjective. We each see it in subtly different ways, and describe it differently and remember it differently. How we feel about a particular color depends on the contexts in which we have encountered it previously. This is one explanation why monochrome paintings evoke such controversy at times. Regardless of what an artist intends by painting one, a monochrome is never finished until viewers look at it and add to its meaning whatever prejudices and preconceptions they brought with them.

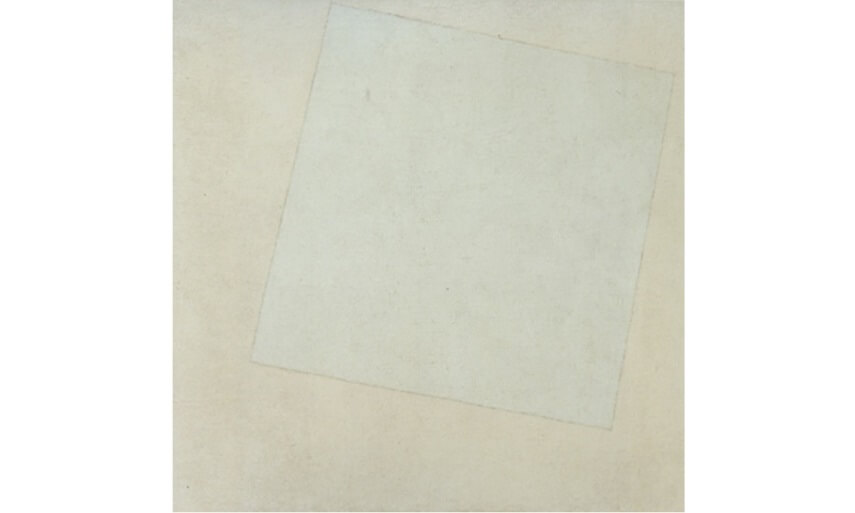

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition, White on White, Oil on Canvas, 1917-1918, 79.4 x 79.4 cm, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition, White on White, Oil on Canvas, 1917-1918, 79.4 x 79.4 cm, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City, NY

Perspective is Everything

Kazimir Malevich and Alexander Rodchenko were Constructivists, a group of artists who believed that the old ways of looking at art, through horizon lines, perspectives, subject matters, etc., were useless in the modern age. They longed for an art that could exist outside of the realm of the personal and could be enjoyed by the entire society. They weren’t trying to kill painting; they were trying to democratize it.

The irony of their effort to make a less personal art is that by simplifying their palette and reducing or even eliminating their vocabulary of forms, they invited more introspection than ever. They created canvases that invited intricate aesthetic appraisals. The depth and complexity of the subtle shades evident in White on White provide careful lookers with infinite hours of contemplative pleasure. And when factors such as lighting and context are considered, entirely new levels of contemplation and interpretation come into play.

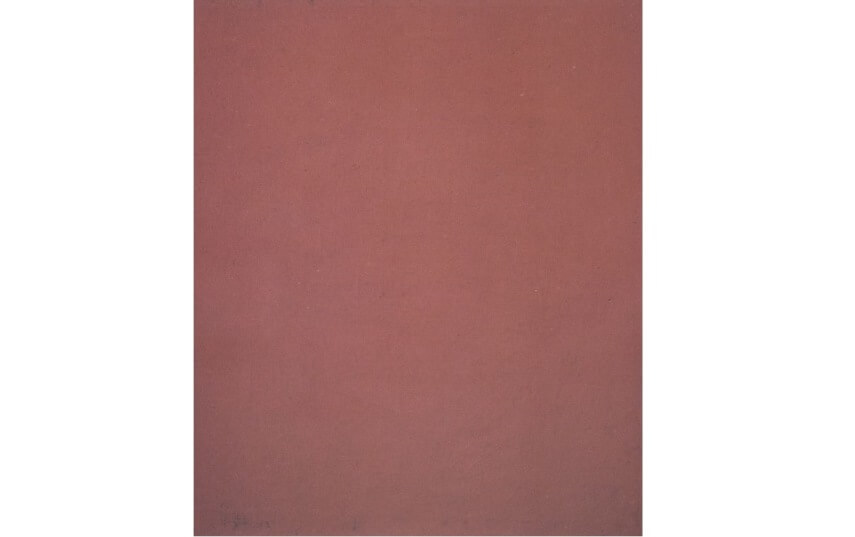

Alexander Rodchenko - Pure Red Color, 1921, Ivanovo Regional Art Museum © A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive / DACS

Alexander Rodchenko - Pure Red Color, 1921, Ivanovo Regional Art Museum © A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive / DACS

Content vs. Context

As early as the 1890s, Claude Monet painted canvases in a single color. But these canvases contained representational content, so the limited palette is easily overlooked in lieu of the houses, trees or ground in the picture. By eliminating all content and focusing solely on color, a monochrome painting forces viewers to contemplate something entirely personal. One viewer might look at a monochromatic red painting and dismiss it entirely. Another might remember something personal about the color red and connect the work with that memory. Another might use the monochrome painting as a spiritual medium through which to connect with something subconscious or universal. Another may simply react to it aesthetically, declaring it beautiful or hideous.

In 1955, the artist Yves Klein exhibited a selection of different colored monochrome paintings. The audiences enjoyed them but interpreted them simply as decoration. In reaction to this misunderstanding, Klein created his own hue of blue and for his next show in 1957 he exhibited 11 identical canvases all painted that exact same color of blue. The color became known as IKB (International Klein Blue), and the effect this exhibition had on audiences was far more profound.

The Void

Klein followed the blue show with a show that was subtitled The Void, in which he removed everything except a cabinet from a gallery space and painted the entire room white. He dyed a curtain IKB and hung it across the entrance to the space. He changed the viewer’s focus from the artistic content of the show to the context in which the art is shown. This shift in perception from content to context dramatically changed the way art could be viewed. And the monochrome painting became the perfect vehicle through which to explore this new perspective.

A monochrome painting can easily become an element through which an environment is enhanced. A monochrome could also become the focal point of an environment, interacting with the context in a way that draws specific attention to itself and nothing else. A monochrome can become the void or it can fill the void. It can reveal the void within the viewer, or a viewer can fill the monochrome’s apparent void with a transferal of experiential content.

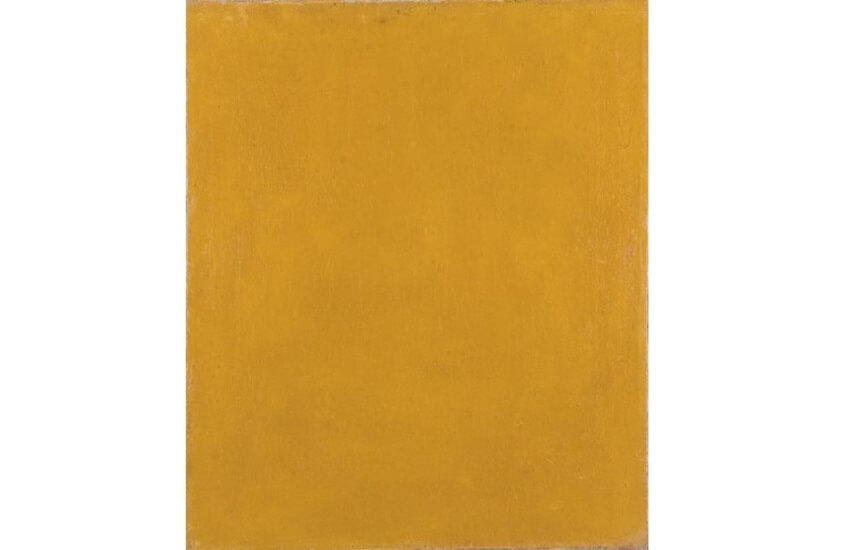

Alexander Rodchenko - Pure Yellow Color, 1921, Ivanovo Regional Art Museum © A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive / DACS

Alexander Rodchenko - Pure Yellow Color, 1921, Ivanovo Regional Art Museum © A. Rodchenko & V. Stepanova Archive / DACS

So What’s a Monochrome?

Simply put, a monochrome’s only defining quality is singularity of color. But a monochrome painting is more than the sum of its components. A monochrome painting is also defined by its ability to transform a viewer or an environment. It communicates something directly, such as, “red,” “blue” or “yellow.” And yet it also communicates nothing. It awaits a seer, a listener, a translator in the mind of a viewer, before settling on what it wants to communicate.

In a way, a monochrome is both the most representational type of painting possible and also the most abstract. It’s a universal totem. It offers us something specific and yet it accepts whatever we have to give.

Featured Image: Yves Klein - Untitled Monochrome Blue (IKB 92), Dry pigment in synthetic resin on canvas, mounted on board, 92.1 x 71.8 cm, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio