The Week in Abstract Art - What You Perceive, You Can Believe

Jun 29, 2016

Do words matter? Sorry, was that the most rhetorical question ever? We were just wondering, does the word abstract really mean what we think it means? What got us on this train of thought is the subject of abstract photography. This weekend, on 3 July, an exhibition of the photography of Paul Strand closes at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. In the early 20th Century, Strand became one of the first photographers to embrace the concept of abstract photography. His work was championed by the famous Alfred Stieglitz in New York. Strand photographed objective phenomena in such a way that highlighted the geometric elements of his subjects, but the subject matter itself is often unrecognizable or “abstracted.” But calling his work abstract is challenging from a perceptual point of view. If something exists in the physical world, and we can touch it and look at it and photograph it, what about it is abstract? But then again, black squares existed before Malevich. Squiggles exist prior to Cy Twombly, and grids before Agnes Martin? So is there really any such thing as abstract art at all?

It’s Not a Lie If You Believe It

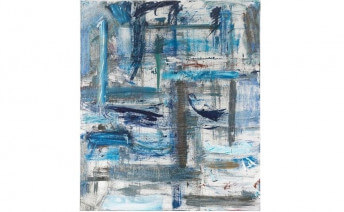

Speaking of abstract photography, on view now through 14 August at the Art Institute of Chicago is an exhibition of 100 of Aaron Siskind’s abstract photographs from the mid-20th Century. In the 1950s, Siskind pioneered a type of “abstract” photography that is extremely common today on almost everyone’s Instagram feed. He took close-up photographs of industrial and urban elements, examining the qualities of surface, composition, line and form inherent in their often-decaying appearance. The images convey much of the same emotion, drama and primal energy of Abstract Expressionist paintings. So if possible, see this exhibition for yourself and answer this question: Were Siskind’s images less abstract than those of the Abstract Expressionists?

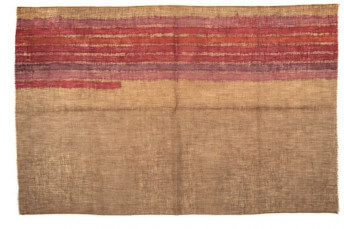

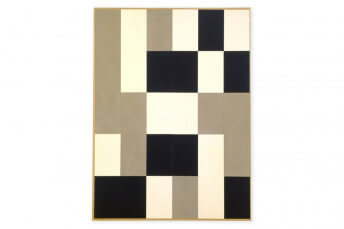

Even the most inventive abstract painting, whether if it references anything that previously existed or not, upon being painted immediately references itself. That’s the unavoidable linguistic paradox of the word abstract. Once something exists, it’s objective. Take for example the work of Sean Scully. Closing this week on 1 July at Cheim & Read gallery in Queens, New York, is an exhibition of Scully’s layered, patterned paintings from the 1970s. These works feature grids on top of grids covered in more layers of grids. They’re called abstract, but they were painted in a time when grids were commonplace in abstraction. But whatever they’re called, they’re hypnotic. Each painting pulls the eye deep into an exhilarating world of depth, color and space. They aren’t endeavoring to create something new, or even to abstract something old. They simply exist. They’re open. Whether you would call them abstract or not is irrelevant.

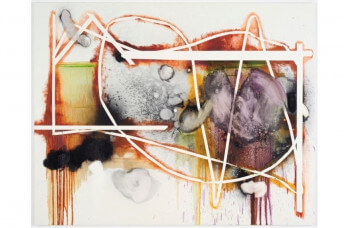

Maybe as art lovers, art collectors and art makers, what should truly matter isn’t whether something references reality or not, because when pressed we would all probably find it tough to even define what exactly reality is. Consider the work of the contemporary Chinese painter Mao Lizi, whose Ambiguous Flower oil paintings are on view at Hong Kong’s Pékin Fine Arts through 10 August 2016. The gallery’s announcement for Lizi’s exhibition, titled A Dream of Idleness, carries with it this poetic sentiment: My heart lives a roaming dream, and the rest evaporates in the autumn wind. This perhaps best sums up our attempt at unraveling whether abstraction, reality, or anything else truly exists, or whether it’s all just part of a futile attempt to qualify and quantify the ungraspable essence of our existence. Lizi calls his flowers not abstract, but ambiguous. Maybe that’s a better word. Abstract art is ambiguous art. Any attempt to define it, to restrict it or to confine it evaporates in the wind.

Featured Image: Mao Lizi - Ambigious Flower Series No.5, 2015