A Feminine Edge: Abstract Sculpture at The Tate Britain

Oct 13, 2015

At Tate Britain, all attention is turned towards feminine abstraction. After so much recent speculation on the role of female artists in the art world, Tate Britain is presenting the first retrospective in 50 years celebrating the work of British sculptor Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975). The exhibition, entitled “Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World”, is showcasing an extensive body of her work and will run until 25 October 2015.

An Artist Not Defined by Her Sex

Although some members of the art market remain close-minded and stuck in the past, believing that female artists are mere shadows of their male counterparts, Barbara Hepworth’s success blows their misogyny out of the water. She says, “I rarely draw what I see, I draw what I feel in my body,” a statement that can be clearly seen in the organic fluidity and natural undulations of her colossal sculptures. Hepworth was part of a select group of sculptors practicing direct carving, a club that included the likes of Henry Moore. She has never sought to be pinned down and confined to the box of ‘female artist’ stamping her feminist mark on the art world. She rejects any suggestion that she sees herself in competition with male artists. When asked by the Feminist Art Journal, Brooklyn, whether her work was confined by domestic concerns, she replied that that was natural for women and that she “hadn’t much patience with women artists trying to be women artists. […] I believe art is anonymous.”

Barbara Hepworth - Pelagos, 1946. Elm and strings on oak base. 43 × 46 × 38.5 cm, 15.2 kg. Tate Collection

Carving a Unique Style

However, there the artist seems to have failed, as her work is anything but anonymous. She started out in the 1940s, producing a series of wooden sculptures painted inside and embellished with a single piece of string stretching from one point to many points. This symbolic cord was almost like a bridge between a sort of utopian spirituality, her state of mind when in nature, and the banal reality. Penelope Curtis, former director and exhibition curator at the Tate Britain, believes that ““What is special about Barbara Hepworth, is that she was, maybe in the United Kingdom, the first artist to really find a properly abstract style and to link it to real organic materials. Her work is very abstract yet very human. She did not use man-made material, she only used natural materials.”

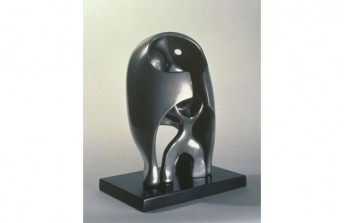

Barbara Hepworth - Curved Form (Trevalgan), 1956. Bronze on wooden base. 90.2 × 59.7 × 67.3 cm. Tate Collection. © Bowness

Photography

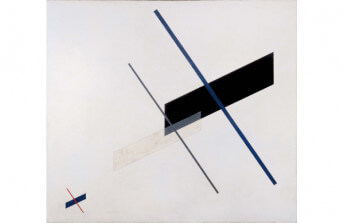

From early on, Hepworth has taken an interest in the perception and reception of her work. Wanting to conserve and capture the image of her works to be published in magazines, journals and books; she began in the 1930s to photograph them. She dappled in various photographic methods, wanting to conserve the three-dimensionality of her sculptures in the two-dimensional images, and so stumbled across the photogram. This process, used by the likes of Hungarian László Moholy-Nagy, involved placing an object on photosensitive paper and exposing it to light. However, for Barbara Hepworth, photography was more a means of documentation than an art form in and of itself, and in the 1950s she abandoned the photogram for video. Penelope Curtis remembers that “She wanted to control her image and the manner in which she was presented. I’m not sure it did any service maybe it made her less popular. She was very sure about the way she wanted her work to be shown, down to the layout of the magazine. I think it just showed how talented she was in positioning the placement, the context in which her work was shown.”

Barbara Hepworth - Discs in Echelon, 1935, cast 1959. Bronze. 34.3 × 50.8 × 27.3 cm, 100 kg. Tate Collection. Presented by the executors of the artist's estate 1980. © Bowness

A National Treasure

According to The Guardian, the odds are at 12:1 for Hepworth to be chosen as the next face to appear on the £20 note, as the British Central Bank has expressed its desire to have an artist on the next note. This time round, there will be a chance for the public to vote, following the uproar of 2013 when Elizabeth Fry was unceremoniously erased from the £5 note in favour of Winston Churchill. The results will be revealed in Spring 2016, although it is clear that she is a well-deserving candidate, having represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1950, an honour which only five female artists have achieved, namely Bridget Riley (1968), Rachel Whiteread (1997), Tracey Emin (2007), and Sarah Lucas this year. However, Penelope Curtis does not count her appearance in Venice as her “favourite display of her work. I think she is a great sculptor but I think she’s done better.”

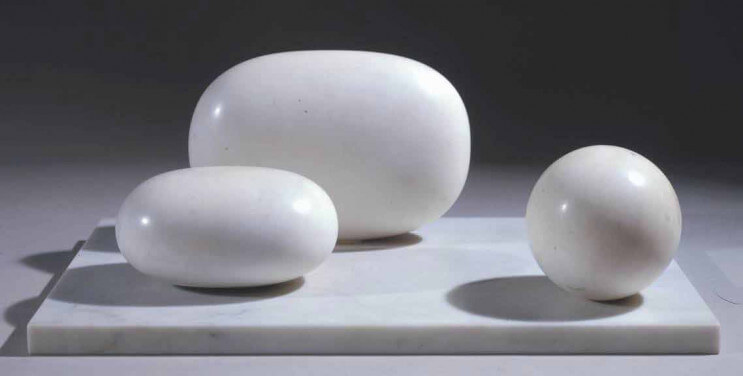

Featured image: Barbara Hepworth - Three Forms, 1935. Serravezza marble on marble base. 21 × 53.2 × 34.3 cm, 23 kg. Tate Collection. © Bowness

All images used for illustrative purposes only