Bridget Riley and the Philosophy of Stripes

Our sensory experiences connect us to a world of emotion. When we see something, that sense, in itself, is a sort of feeling. But then we also feel things based on what we see. Those feelings are what British artist Bridget Riley has spent the last six decades examining. In the 1960s, Riley became famous for her contributions to an artistic movement known as Op Art, so named for the optical illusions viewers often perceive in the work. Op Art rose to global prominence after the success of an exhibition called The Responsive Eye at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1965. Several paintings by Bridget Riley were included in that exhibition. They featured a sparse black and white palette and repeating patterns that created a sense of dynamism that made viewers feel unstable, or off balance. The patterns in her paintings seemed to move. But the work of Bridget Riley is about much more than simply fooling the eye with an optical illusion. It is about perception. It is about how carefully we look, how precious we believe our gift of vision to be, and how our emotions can be affected by the way we see our world.

The Young Bridget Riley

As a young artist, Bridget Riley was often frustrated. She had cherished being able to freely explore the environment around her various childhood homes in London, Lincolnshire and Cornwall. She had an innate curiosity and a desire to experiment. But in her 20s, while studying at the Royal Academy of Art, she found her curiosity and experimental spirit discouraged by her professors. She graduated unsure of herself. And her lack of direction was quickly exacerbated when her father was soon after hospitalized after a car accident, and she became responsible for his care. The combined stresses led her to suffer a complete breakdown.

The turning point towards recovery came for Riley was when she visited an exhibition of the Abstract Expressionists at the Tate in London in 1956. Their work validated her desire to experiment and to explore her true vision, and she soon began painting again. She found work teaching art to young girls and took a job as a commercial illustrator. Then she signed up for a summer class with Harry Thubron, who was known for espousing the power of elements like spatial relationships, forms and patterns.

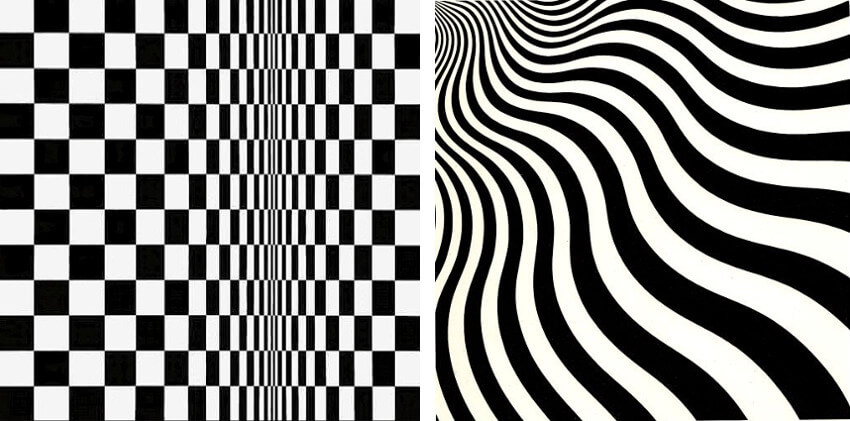

Bridget Riley - Movement in Squares, 1961. Tempera on hardboard. 123.2 x 121.2cm. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © 2019 Bridget Riley (Left) / Bridget Riley - Intake, 1964. Acrylic on canvas. 178.5 x 178.5 cm. © 2019 Bridget Riley (Right)

Bridget Riley - Movement in Squares, 1961. Tempera on hardboard. 123.2 x 121.2cm. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. © 2019 Bridget Riley (Left) / Bridget Riley - Intake, 1964. Acrylic on canvas. 178.5 x 178.5 cm. © 2019 Bridget Riley (Right)

Optical Realities

In her study with Harry Thubron of the formal elements of aesthetics, especially in how the eye perceived forms in space, Riley became rededicated to finding her authentic voice. She moved to Italy in 1960 and studied the works of the Futurists. Inspired by their exploration of movement she went on to study the ideas of the Divisionists, especially Georges Seurat. The sum of these studies led her to develop a singular approach to painting: one in which she explored ways to transform a two-dimensional surface in order to affect visual perception.

She knew that in order to challenge the way viewers looked at a painting, she would have to eliminate all representational content. Representational images would only distract from her primary ideas. So she simplified her visual language to utilize only black and white and the elements of line, shape and form. In the catalogue for The Responsive Eye, curator William C. Seitz called work like what Riley was making “the new perceptual art.” Seitz raised the bar of expectation for what this art could accomplish far beyond the realm of something purely aesthetic. He asked, “Can such works, that refer to nothing outside themselves, replace with psychic effectiveness the content that has been abandoned? Can an advanced understanding and application of functional images open a new path from retinal excitation to emotions and ideas?” These were exactly the types of questions Riley was asking herself.

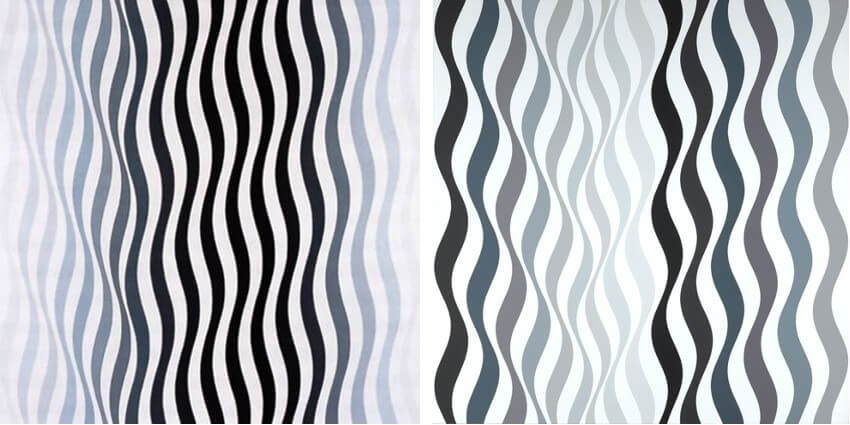

Bridget Riley - Arrest 1, 1965. Emulsion on Canvas, 70 x 68 1/4 in. © 2019 Bridget Riley (Left) / Bridget Riley - Arrest 2, 1965. Acrylic on linen. Unframed: 6 feet 4 3/4 inches x 6 feet 3 inches (194.95 x 190.5 cm). Framed: 6 feet 7 3/8 inches x 6 feet 5 3/4 inches x 2 3/4 inches (201.61 x 197.49 x 6.99 cm). The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art Collection. Acquired through the generosity of the William T. Kemper Foundation - Commerce Bank, Trustee. © Bridget Riley. All rights reserved, courtesy Karsten Schubert, London (Right)

Bridget Riley - Arrest 1, 1965. Emulsion on Canvas, 70 x 68 1/4 in. © 2019 Bridget Riley (Left) / Bridget Riley - Arrest 2, 1965. Acrylic on linen. Unframed: 6 feet 4 3/4 inches x 6 feet 3 inches (194.95 x 190.5 cm). Framed: 6 feet 7 3/8 inches x 6 feet 5 3/4 inches x 2 3/4 inches (201.61 x 197.49 x 6.99 cm). The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art Collection. Acquired through the generosity of the William T. Kemper Foundation - Commerce Bank, Trustee. © Bridget Riley. All rights reserved, courtesy Karsten Schubert, London (Right)

The Responsive Public

The public response to The Responsive Eye was ecstatic. The mesmerizing, illusory effects of the imagery in the show drove viewers wild. Designers quickly appropriated the black and white patterns and used them on every conceivable product, from dresses to eyeglasses to lunchboxes to cars. But that wow factor held little appeal for Riley, who was more interested in the deeper meanings of her work. Yes, it looked cool. But she wanted to discover the mental processes at work underneath surface appearances.

In 1966, just as her black and white style had gained international appeal, Riley embarked on an effort to dig deeper into her vision by adding color to her work. She spent two years studying and repeatedly copying the Georges Seurat Pointillist painting Bridge of Courbevoie. In it, she saw a mastery of linear structures and patterns. She also saw a mastery of color combinations, a demonstration of how different colors placed beside each other in thoughtful ways create a sense of motion when perceived by the human eye.

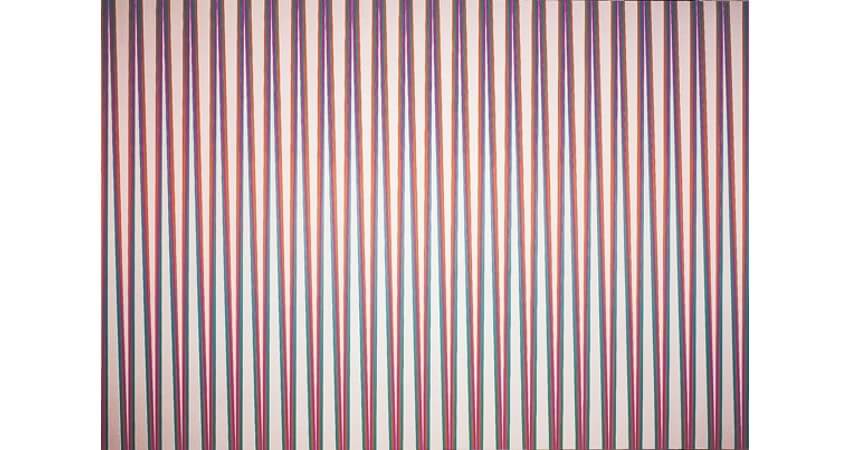

Bridget Riley - Orient IV, 1970. Acrylic on canvas. 223.5 x 323 cm. © Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley - Orient IV, 1970. Acrylic on canvas. 223.5 x 323 cm. © Bridget Riley

Stripes Forever

While complicating the color palette she was using, Riley simultaneously simplified her language of forms. She all but eliminated squares, triangles and circles, and focused largely on stripes throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Stripes lend themselves easily to a study of repetition, which Riley perceived as essential to getting people to really look at an image with intention. The form of a stripe is also fundamentally stable. That stability, she discovered, is vital to the study of color because color is fundamentally unstable, since perception of it depends on other factors like light and surrounding colors.

Riley used a combination of straight and wavy horizontal and vertical stripes. She began each piece on small strips of paper, testing color combinations and patterns. Once she arrived at a color combination and stripe pattern that seemed to move, she transferred it to a large canvas that she then hand painted. Each stripe in her colorful stripe paintings incorporates within it an evolution of different colors melding into each other in precise ways, so that the eye, when looking at each stripe, perceives a hint of the next color. That evolution creates the sense of motion as the eye travels across the surface.

The Sight of Music

While the stability of stripes was vital for her discovery of color, ultimately the color was what helped her achieve her aesthetic vision. She said, “The music of colour, that’s what I want.” As so many other artists, from Seurat to Giacomo Balla to Sonia Delaunay to Josef Albers, had realized, every color is capable of evoking an emotional response. And when used together, various colors seem to vibrate, creating unpredictable emotional responses in viewers. That unpredictability helped Riley to achieve her ideal goal for a painting, which she said must “offer an experience; offer a possibility.”

The aesthetic discoveries Riley has made through her colored, striped paintings came about because she is a precise experimenter. She keeps rigorous notes of each color combination and pattern that she tries, so that it can be repeated if necessary. But though her experiments with colors and stripes seem scientific, they are not, at least not in the sense that they were trying to prove a hypothesis. Rather they are artistic, in the sense that they seek to discover an unknown and to manifest it.

Bridget Riley - Carnival, 2000. Screenprint in colors, on wove paper, with full margins. 28 3/5 × 35 9/10 in. 72.7 × 91.1 cm. Edition 55/75 + 10AP. © 2019 Bridget Riley

Bridget Riley - Carnival, 2000. Screenprint in colors, on wove paper, with full margins. 28 3/5 × 35 9/10 in. 72.7 × 91.1 cm. Edition 55/75 + 10AP. © 2019 Bridget Riley

Primary Objectives

Today, in her mid-80s, Riley continues to paint. She now explores a mixture of geometric forms, wavy forms and diagonals. The patterns of her newer paintings are far wider, creating a much different impression, and evoking much different feelings. Her striped paintings of decades past stand as powerful manifestations of her life long inquisition into perception. They go far beyond merely tricking the eye into a realm of deep, subjective perception.

What is important about these works is that they challenge not only our way of seeing them, but also our way of seeing everything. The stripes Riley uses are as simple, perhaps, as forms can be. Yet the metamorphoses that become apparent while examining them seem limitless. Riley once said, “Repetition acts as a sort of amplifier of visual events which seen singly, would hardly be visible.” Her stripes demonstrate that philosophy: that complexity lurks beneath the seeming simplicity of our visual world, if we only take the time to really notice. They implore us to look carefully and closely, and to fully appreciate the precious gift of seeing.

Featured image: Bridget Riley - Conversation (detail), 1992. Oil on linen. 92 x 126cm. Abbot Hall Art Collection. Purchased in 1996. © Bridget Riley

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio