Abstraction in Photography of László Moholy-Nagy

Today, photography is ubiquitous. Cameras are imbedded in billions of electronic devices, and it is hard to imagine any subject that has not been thoroughly explored ad nauseam in photographs. But what is the status of photography as abstract art? In 1925, the Hungarian artist and Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy complained that, although photography had existed for more than 100 years at the time, artists used it for little more than the reproduction of reality. He said, “the total result to date amounts to little more than a visual encyclopedic achievement.” He called most photographs nothing but an “arrested moment from the moving display.” Now, nearly 100 years later, we still primarily use photography for reproduction, not production. In Painting, Photography, Film, his seminal book on the topic, Moholy-Nagy pontificated at length on the multitude of other possibilities photography might promise to artists willing to pursue its abstract potential. Foremost among those possibilities in his opinion was the potential for photography to create “new relationships between the known and the as yet unknown.”Moholy-Nagy believed that we are at our best when all of our biological systems are working in synthesis with eachother,and that integral to that state of total functionality is the incorporation of a regular flow of novel sensations. For artists, that means the greatest contribution one can make to the elevation of the human race is to offer new sensory experiences; not by simply imitating, or photographing, what already exists but rather by offering perspectives on how to see the world anew.

The Personal and the Universal

Art is not a topic to easily generalizeabout,because nearly every artist strives for originality. Outside of those moments when a group of artists signs a manifesto describing exactly what they are doing, it is almost impossible to lump artists into a movement or a particular point of view. Nonetheless, it is occasionally accurate to say that a common tendency was or is being adopted by a particular group of artists, and to talk in a general way about what that tendency seems to be. (If that sounds like a caveat, that is because it is.) Two of the most commonly generalized tendencies that seem to occur within abstract art are the tendency toward aesthetic expressions that are personal, and the tendency toward aesthetic expressions that are universal.

Personal expressions are generally somewhat subjective, or ambiguous; universal expressions are generally objective, or unambiguous. These two tendencies manifested in a distinct way among many of the early Modernist abstract artists. On one side were artists like Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian who espoused a geometric, objective sensibility. On the other side were artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee who sought to express their personal quest for the spiritual. This is an oversimplification, but one way to put it is that one side was emotional, and the other side was practical. But all were hoping to achieve something universally valuable, though their perspectives were quite different, and their approaches often diametrically opposed.

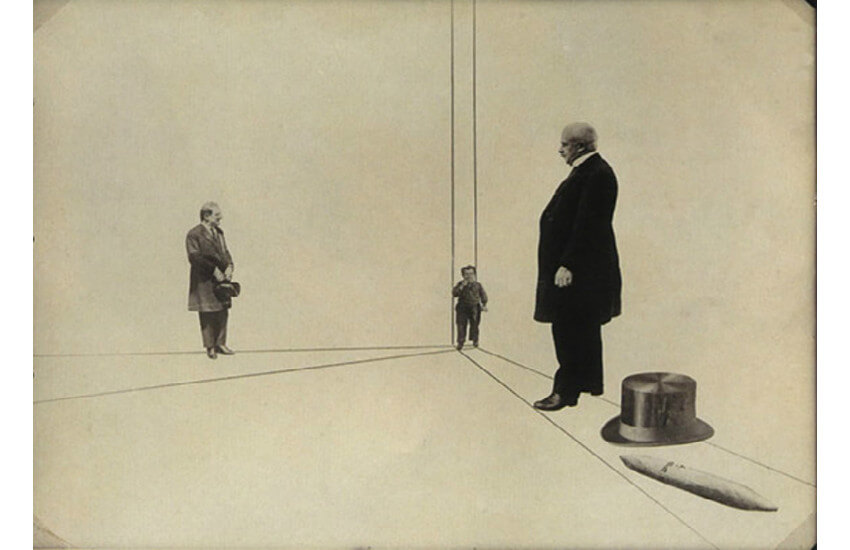

László Moholy-Nagy- Unsere Grossen, 1927. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

László Moholy-Nagy- Unsere Grossen, 1927. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

Black and White

Until he was nearly on his deathbed, László Moholy-Nagy was firmly on the side of the practical artists. One story about him claims that nearing death he renounced his disdain for emotional art, and announced the importance of subjectivity. But when he was the most influential, while he was at the Bauhaus and while he was engaged in photography, he was as unambiguous as they come. His frame of mind was that artists should use photography in accordance to its objective function as a medium. That function, as he put it, is the ability to convey chiaroscuro.

Chiaroscuro is the portrayal of the qualities of lightness and darkness in a painting. Paintings with extreme differences between shadow and light are said to contain a high degree of chiaroscuro. László Moholy-Nagy perceived photography as a medium primarily concerned with light, and thus considered it the ultimate medium through which to portray chiaroscuro. He saw this as the highest use of the medium, and many of his earliest abstract photographs were intended as pure, formal compositions of white, black and shades ofgrey. These images become abstract when we focus on thechiaroscuro,because we acknowledge that the object being photographed is not the subject, but that the subject is an idea, in thiscasethe idea of lightness and darkness.

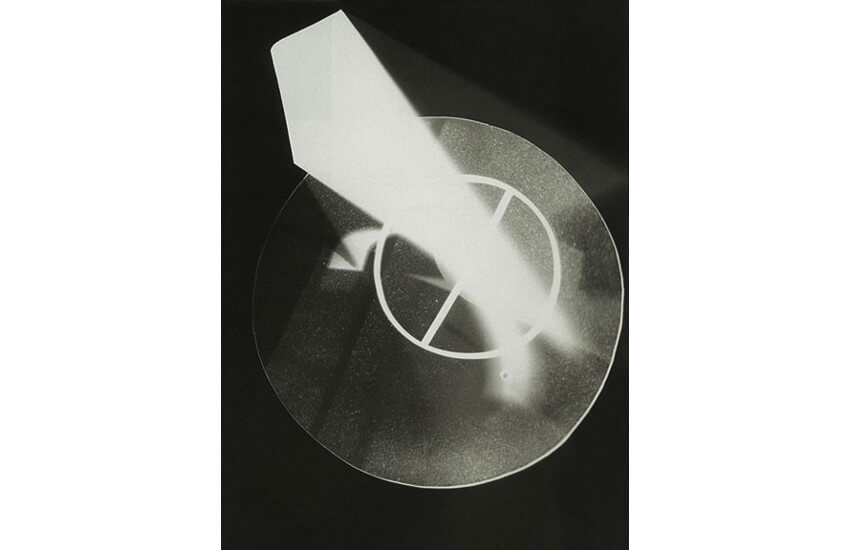

László Moholy-Nagy - Untitled, Photogram, Dessau, 1925-8. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

László Moholy-Nagy - Untitled, Photogram, Dessau, 1925-8. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

The Mystic Mundane

In addition to chiaroscuro, László Moholy-Nagy also identified several other unique abstract qualities he believed were inherent to photography, all of which he sought to express in his work. One is the ability to transform something mundane into something magical through the manipulation of formal elements like exposure and composition. All around us, imagery exists that, if we were able to see it from a certain perspective we would appreciate its surreal, dreamlike, or even mystical aesthetic properties. But our true experience of the world limits our perspective and inhibits us from selecting what we see and how we see it.

A camera inherently sees reality from an edited point of view. It can freeze a moment and extend it forever in time. Photography also exploits the fact that the human mind instinctively perceives anything the eye sees in a photograph as reality. Even though a photograph shows us only a partial view of the world, one that has been manipulated by the artist, our mind still interprets it as true. This can cause something familiar to seem unfamiliar, or viceversa,and that uncanny experience can create a sense that what we are seeing somehow transcends the natural.

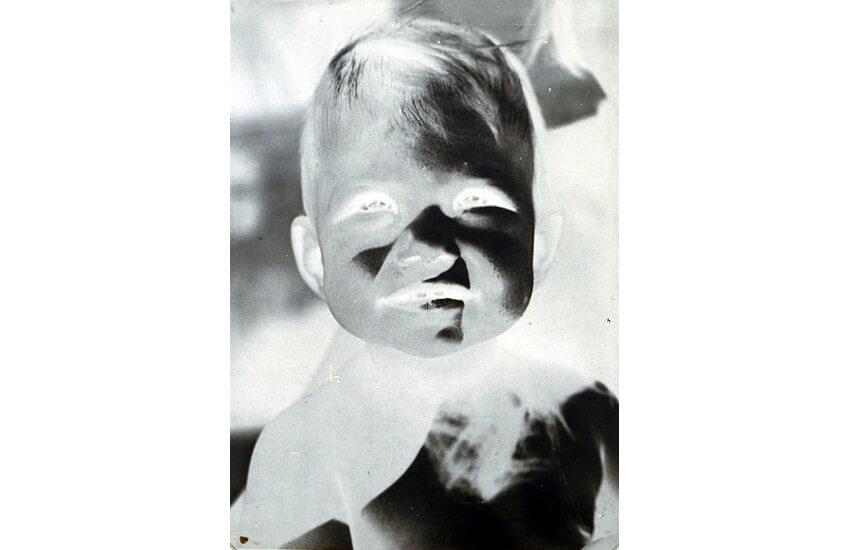

László Moholy-Nagy - Portrait of a Child, 1928. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

László Moholy-Nagy - Portrait of a Child, 1928. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

Mindful Multiplicity

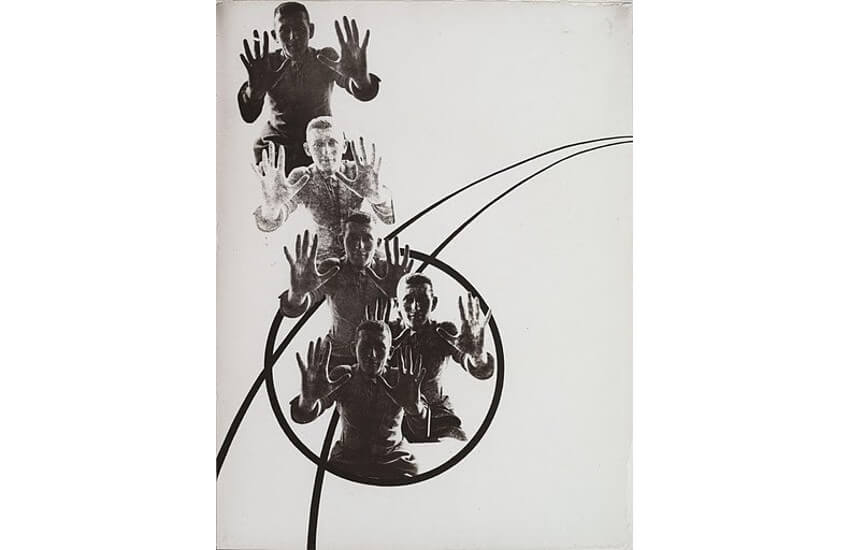

Another potentially abstract quality in photography is the ability the artist has to use the medium to create multiplicity. László Moholy-Nagy accomplished multiples in various ways in his photographs. Sometimes he exposed a negative multiple times, creating compositions that contained simultaneous different perspectives on a single subject; much like a Cubist painting. Other times he made a print that featured multiples of the same image, resulting in strange compositions of repeating identical objects.

While looking at these images our mind struggles to identify what it should consider as the subject matter. Is the subject the recognizable image of a person or an object? Should we ignore the fact of multiple images or multiple perspectives? Or is the subject matter the idea of repetition? In truth, the subject matter is the fact that we do not know the subject matter. It is the abstract representation of the as yet unknown.

László Moholy-Nagy - The Law of Series, 1925. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

László Moholy-Nagy - The Law of Series, 1925. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

Truth Through Distortion

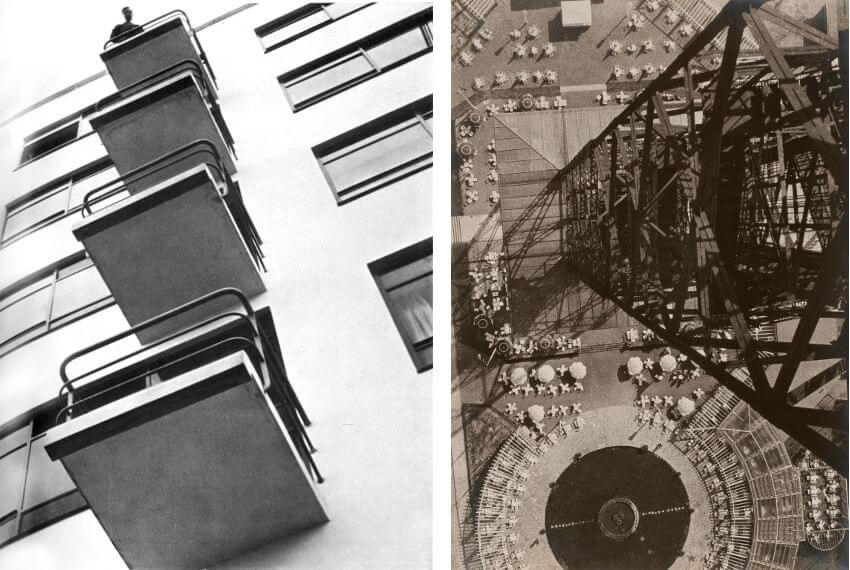

Perspective may be the most powerful abstract tool a photographer possesses. A photograph allows the whole world to see whatever a single camera can see. In one sense, perspective heightens the ability of a photograph to show us reality. For example, in his famous photograph Balconies, Moholy-Nagy gives us a new perspective on the harmonious composition of objects in the real world by capturing the geometric composition of architecture in the sunlight. This is the visual truth of our ordered, geometric environment, as our limited eyesight will not allow us to see it.

In another sense, perspective heightens the ability of a photograph to distort reality. In his photograph called Berlin Radio Tower, Moholy-Nagy shows us a point of view so subjective that it is almost kitschy. This is our world as we will likely never see it in real life, or need to see it. This isreality, but not our everyday reality. We can appreciate the photograph purely according to its objective subjectmater, or we can appreciate its compositional elements, removed from any personal responsibilitytothe content. Or we can interpret the subject matter as the abstract notion of our usual inability to see a wider perspective on our world.

László Moholy-Nagy - Balconies (Left), and László Moholy-Nagy - Berlin Radio Tower (Right). © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

László Moholy-Nagy - Balconies (Left), and László Moholy-Nagy - Berlin Radio Tower (Right). © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

New Ways to See

Many of the photographs László Moholy-Nagy created seem distorted, obscured or intentionally abstracted. But he did not define them according to those properties. He saw the camera as a tool through which a heightened, universal reality could be expressed. But in order to express that heightened reality he believed the camera had to be used “in conformity with its own laws and its own distinctive character.”

He defined the distinctive character of photography as something simultaneously objective and abstract. Photography capturesreality,but does not always limit its subject matter to the reality it captures. Instead, the subject matter revolves around notions of lightness and darkness, the mystery of perspective, the ability to freeze motion and the power to extend time. Through his work, Moholy-Nagy demonstrated how abstract photographs are not necessarily distortions, but rather in the hands of a visionary artist can be, “An invitation to re-evaluate our way of seeing.”

Featured image: László Moholy-Nagy - Composition Z VIII, 1924. © László Moholy-Nagy Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio