Why Do Abstract Art Images Make us Feel so Good?

When you look at abstract art images, how do they make you feel? Do you find that they tend to cause you to have a visceral emotional response? Does abstract art make you feel happy? Does it make you feel sad? Does it make you angry? Does it cause you to feel at peace? In 2016, Nobel prize winning American-Austrian neuroscientist Eric Kandel wrote a book titled Reductionism in Art and Brain Science, which postulated that several links could be drawn between the process of creating abstract art and the process of studying brain science. His theory was founded on the idea of reductionism, or simplification. Kandel believes that by reducing a problem to its simplest elements it can be more widely and more easily understood. His book explores the way reductionism is essential to science and was also essential to the great advancements in 20th Century abstract art. By reducing aesthetic principles to their most essential state, Kandel suggested that great abstract artists create images that connect more directly with viewers in ways that manifest in heightened emotional responses. The topic definitely has us wondering: why does abstract art make us feel so good?

The Way To Be Happy

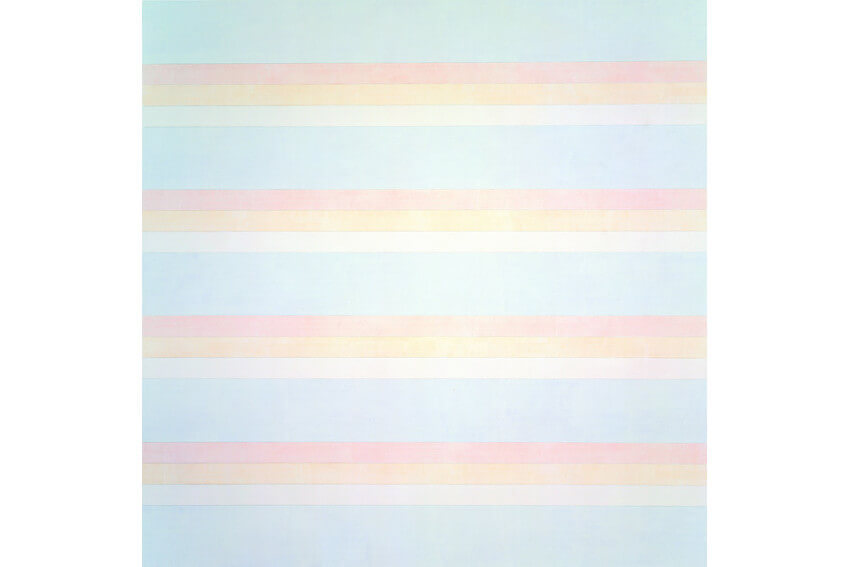

The abstract painter Agnes Martin talked a lot about happiness. She professed that it was her goal to make paintings that communicate a sense of joy. About happiness specifically, she once said, “There are so many people who don’t know what they want. And I think that, in this world, that’s the only thing you have to know — exactly what you want. … Doing what you were born to do … That’s the way to be happy.” It is no surprise that Martin described herself as being happy, since she was undoubtably doing exactly what she was born to do. But we are curious about exactly how and why she thought her paintings would make the rest of us feel happy or joyful when we look at them.

Going back to what Eric Kandel suggests in his book, reductionism might have something to do with the answer to this question. Agnes Martin was known for taking a reductionist approach to painting. She once described her grid paintings as being reduced images of rows of trees, which for her represented a vision of joy. But it is highly unlikely that the average viewer, when looking at an Agnes Martin grid painting, would identify such imagery with trees. It is also unlikely that the average viewer would associate trees with joy, necessarily. Nonetheless, over and again people have indeed reported feeling a sense of joy, happiness, peace and calmness when looking at Agnes Martin Paintings. Maybe the reason why has something to do with the idea that looking at abstract art gives our brain a chance to do what it was born to do.

Agnes Martin - Untitled #2, 1992. Acrylic and graphite on canvas. 72 × 72 in. 182.9 × 182.9 cm. © 2019 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Agnes Martin - Untitled #2, 1992. Acrylic and graphite on canvas. 72 × 72 in. 182.9 × 182.9 cm. © 2019 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

What We Were Born To Do

Depending on who you ask you are likely to hear a lot of different responses to the question of what exactly humans were born to do. Some may think we were just born to reproduce. Others way think we were born to lead spiritual existences. Others may think we were born to fulfill our animal instincts. But in the opinion of brain scientists like Eric Kandel, we were born to think and we were born to feel. And if that is indeed the case then it would make sense that looking at abstract art images would be something that is satisfying and may ultimately result in happiness, because it engages us on both levels: thinking and feeling.

When we look at an abstract image, we do not have the benefit of objective imagery to help us recognize objects or narratives. We do not have human figures to connect with or any sense of a storyline to follow. We only have the essential formal elements of the image: we have lines, shapes, colors, forms, textures, lightness, darkness, etc. We are left to confront these elements without any prior knowledge of what exactly they mean. Where as a figurative work of art might allow every viewer to engage with it on the same level by referencing some aspect of history or life with which we are all familiar, an abstract artwork requires that every viewer that sees it begins anew, using their thoughts and feelings to arrive at some conclusion about what it could possibly mean.

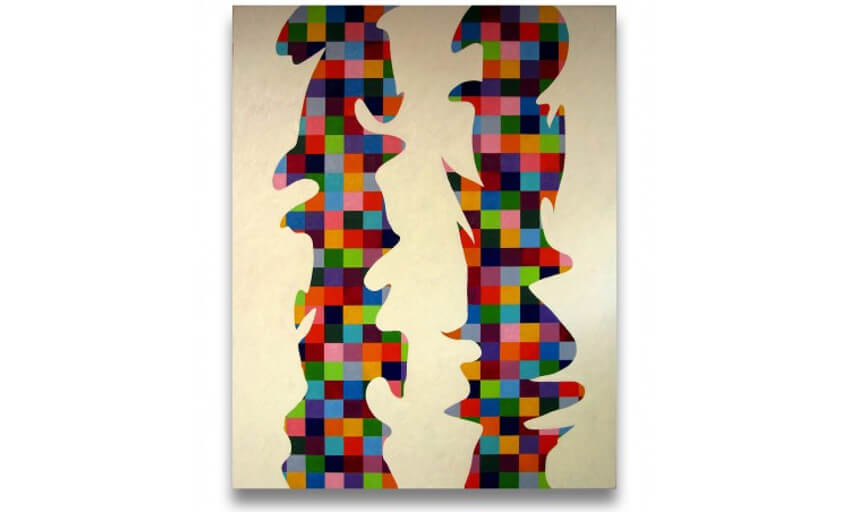

Dana Gordon - Endless Painting 2, 2014. Oil on canvas. 78 x 59.8 in

Dana Gordon - Endless Painting 2, 2014. Oil on canvas. 78 x 59.8 in

Out Of Our Minds

The American philosopher and cognitive scientist Dan Dennett once offered the following advice to those seeking to experience happiness: “Find something more important than you are and dedicate your life to it.” It would be hard to make the case that an abstract work of art is more important than the person viewing it. But there is something about what Dennett said that nonetheless seems to apply to the process of looking at abstract art. When we look at a painting that reminds us of ourselves, we remain stuck in our normal state of self-interest. But when we look at an artwork that has no physical resemblance to us, we are immediately transported out of our typical mindset.

It is universally pleasurable to forget about normal concerns. Any welcome distraction from our routine makes us feel good. An abstract artwork offers a chance to make something outside of ourselves temporarily more important than whatever we were previously thinking about. We now have a chance to look at this image or object and think about what it is, what it might reference, what it might mean, and what its importance might be to us and to the rest of the world. If you have ever heard someone say that abstract art drives them out of their mind, they may have literally been telling the truth. It pulls us out of our usual mental state, offering us a chance of at least momentary transcendence.

Joanne Freeman - Covers 13 - Black A, 2014. Gouache on handmade Khadi paper. 13 x 13 in

Joanne Freeman - Covers 13 - Black A, 2014. Gouache on handmade Khadi paper. 13 x 13 in

Our Definition of Self

Going back to what Agnes Martin said about doing what we were born to do, we can see another possible reason why abstract art images might make someone feel good. It has to do with how we define ourselves in a social sense. One of the most common ways humans have always defined themselves has to do with who their friends are and who their enemies might be. If we belong to a religion, a social class, a club or a nation, we define ourselves in that way and that makes us feel secure. But by defining what we are we are also explicitly defining what we are not. If we are American, we are not Canadian or Australian. If we are Jewish, we are not Shinto or Buddhist. Thus by declaring our loyalty we also declare our opposition, which helps us understand our purpose.

Abstract art gives many people a handy enemy. By positioning themselves in opposition to a particular image, a particular artist, a particular movement, or to abstract art in general, a person can be defined according to that opposition. “I am not that,” they can say, and then they know, conversely, what they therefore are. Their purpose is to oppose their enemy: abstract art images. But then to others abstract art can also be an ally. It can be a friend. Some look at it and relate to it, either because they feel that they understand it or because they feel that its lack of obviousness, lack of content, lack of narrative, and lack of easy explanation is something to which they simply, for some reason, feel a kindred.

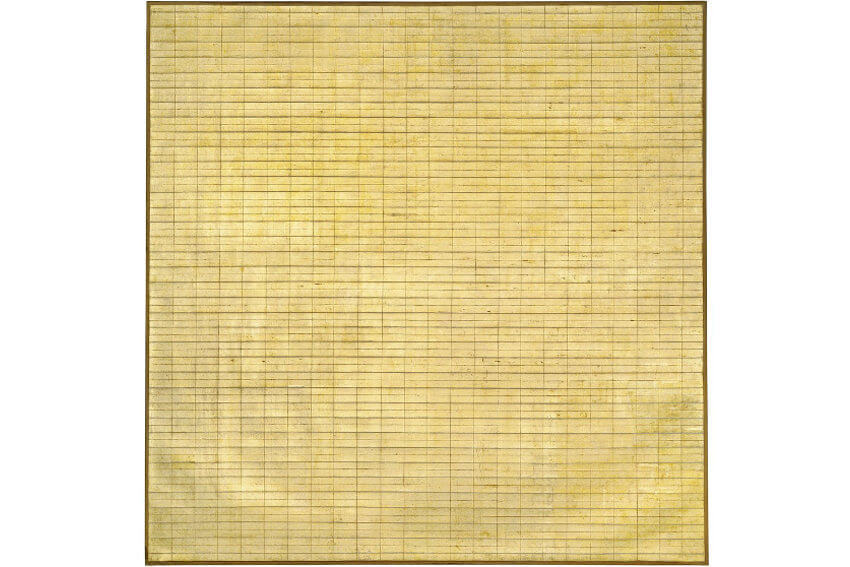

Agnes Martin - Friendship, 1963. Incised gold leaf and gesso on canvas. © 2019 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Agnes Martin - Friendship, 1963. Incised gold leaf and gesso on canvas. © 2019 Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Simplify, Simplify

The American philosopher and author Henry David Thoreau once wrote his own advice on how to be happy. He said, “Simplify, simplify.” Abstract art is an excellent exploration of the validity of his humble advice. As Eric Kandel discovered in his research, the history of Western abstract art has been a process dedicated to simplification. Rather than being bogged down in the complexities of the human drama, abstract artists seek some other aesthetic realm. They dwell in a world of shapes and forms and other objective aesthetic elements, or they simplify the realistic world through a process of paring it down to its base elements, as Agnes Martin did by abstracting trees into horizontal lines.

Whether by simplifying the visual world, by simplifying the aesthetic components of a particular image, or by simplifying the content they are hoping to address, abstract artists offer a more direct, less complicated alternative to realism. And while it could be argued that academics, historians and critics are guilty of complicating abstract art by attempting to explain it, nonetheless, the art itself is not complicated. It is visceral and self-explanatory. For those of us seeking opportunities to get a break from ourselves, to get out of our minds for a moment, to define ourselves, or to connect in some way with what we were born to do, abstract art is great at helping us feel good.

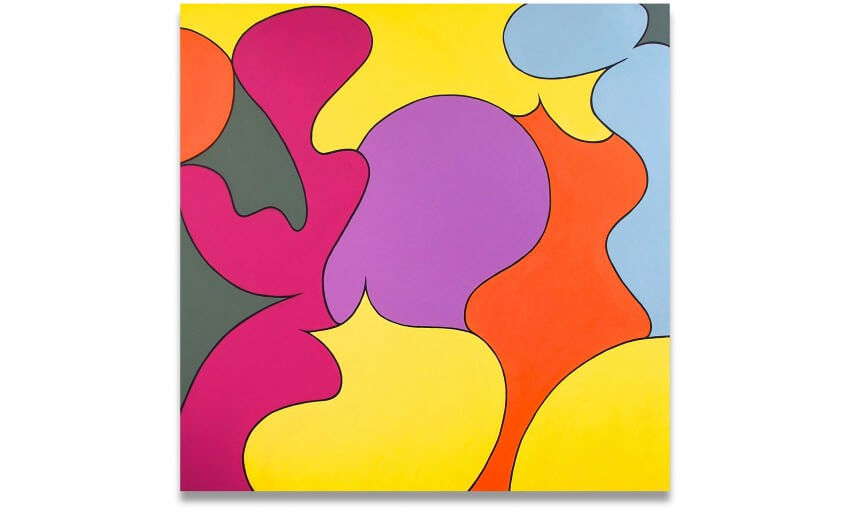

Jessica Snow - Six Color Theorum, 2013. Acrylic on canvas. 48 x 48 in

Jessica Snow - Six Color Theorum, 2013. Acrylic on canvas. 48 x 48 in

Featured image: Agnes Martin -