On Abstract Illusionism - Taking Reality Out Of Illusion

Thanks to the spread of COVID-19, the art field has entered a strange time of extreme flatness as every exhibition in the world is re-imagined in digital form. That makes this the perfect time to look back at the under appreciated, and misunderstood movement called Abstract Illusionism, the whole purpose of which was to reclaim the element of depth. Chances are you have never even heard about this movement, because it is almost never taught in art history classes today. Why not? My guess is because it was too successful for its own good. It was so popular that it spread beyond the art world, into every aspect of visual culture, where it was thus reduced to a gimmick. Abstract Illusionism is basically an amalgam of trompe l’oeil (a French term meaning “deceive the eye”) with mid-20th century abstract art tendencies like Abstract Expressionism and Geometric Abstraction. Trompe l’oeil painters trick viewers into thinking they are actually looking at reality, fooling the eye through hyper-realistic textures, tones and colors, inviting viewers to walk into the illusionistic frame and disappear into the painted world. Most artists consider abstraction to be the opposite of trompe l’oeil. The Abstract Illusionists, however, found inspiration in the trompe l’oeil idea that a painting could become a surrogate for reality. Instead of using this idea to replicate reality, however, they used it to make formal abstract elements like lines, brush strokes and shapes—which have no meaning or relationship to representational reality—seem to exist, by protruding them outwards towards us, seemingly as part of our actual environment. The artists associated with this movement were so good at what they did that by the 1980s, when the movement was at its height, their techniques were being deployed by every graphic designer on the planet. When you look back at the visual language of that decade today, everything from video game graphics to album covers borrows the lessons of Abstract Illusionism—a disappointing legacy for a movement that was so successful that it was beaten into the ground by the public that adored it.

Impossible Perspectives

Despite the awful fate they ultimately suffered, the Abstract Illusionists are at least in good company. They are joined by a laundry list of other artists who became too popular for the art world to love. One in particular who comes to mind is Maurits Cornelis (M. C.) Escher, a Dutch artist who specialized in creating complex woodcuts of scenes that showed seemingly impossible spatial realities. His most famous images are the staircases that seem to go up, down and sideways at the same time, and his picture of two hands drawing each other into existence. Despite being one of the most accomplished, and most cunning, drawers in human history, he was all but ignored by art world insiders, who considered his work to be kitsch. Escher was 70 years old before his work was given a proper retrospective. Yet, the work of pioneering (and much more famous and respected) Op Artists like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley absolutely rely on the techniques that Escher perfected.

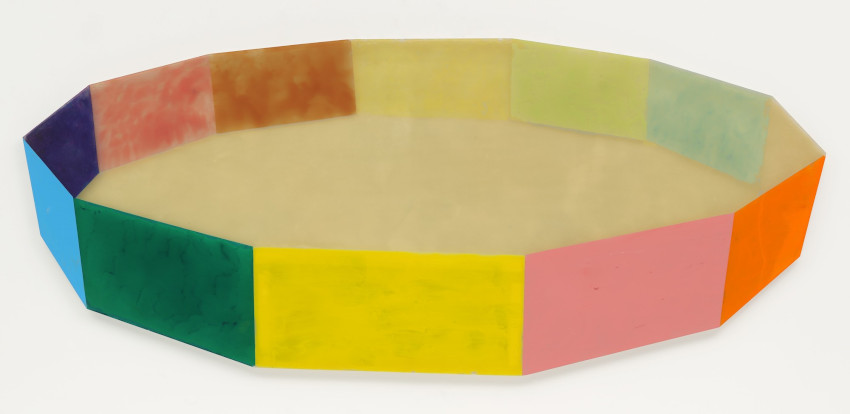

Ron Davis - Ring, 1968. Polyester resin and fiberglass. 56 1/2" x 11' 4" (143.4 x 345.6 cm). MoMA Collection. Mr. and Mrs. Samuel C. Dretzin Fund. © 2020 Ron Davis

Abstract Illusionism not only suffered this same fate, but the artists who pioneered it also drew directly from the techniques and theories that Escher developed. The things in their paintings are not real; they cannot be real; and yet when we look at them our minds become convinced of their realness. When we look at a Jackson Pollock painting, we have a choice to become lost in its intricacies, or to admire the tactile qualities of its impasto layers. But when an Abstract Illusionist creates a splatter painting, our mind is endlessly pestered by the illusion that the brush strokes and splatters are floating in space. Transcendence becomes impossible while our eyes and brain fight to reconcile the illusion. If we know what we are seeing is just patterns, brush marks, and colors, we can address the work on that formal level. By making these elements seem to exist in real space independent of intent or meaning or subject matter, the Abstract Illusionists force us to considere them as actual objects, things with a right to exist in the same world as rocks and dust bunnies and bananas, things with a role to play in our experiential ecosystem.

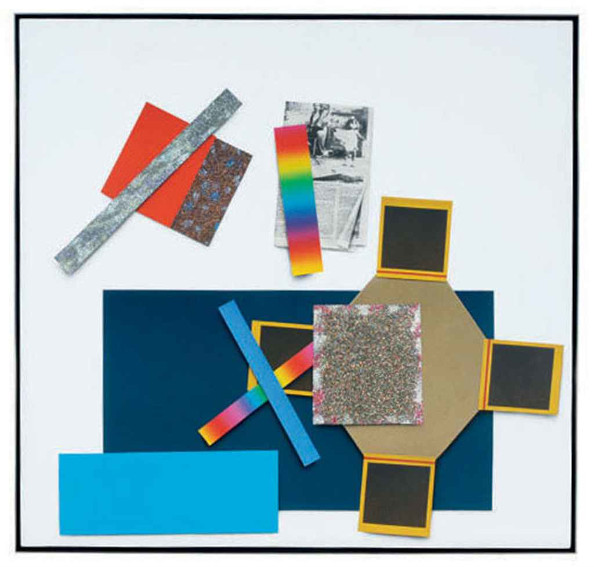

Paul Sarkisian - #6,1981. Acrylic, glitter and silkscreen on canvas. 43 x 45 in. (109.2 x 114.3 cm). © Paul Sarkisian

The Reality of Illusion

If trompe l’oeil is the illusion of reality, and abstraction is the expansion of reality, Abstract Illusionism could be thought of as the expansion of the reality of illusion. In 1979, the Denver Art Museum solidified the legacy of the movement with an exhibition titled exactly that: Reality of Illusion. The exhibition canonized a small group of artist who are now considered the pioneers of Abstract Illusionism, including Joe Doyle, James Havard, and Jack Reilly. Doyle combined geometry and expressionism, making whimsical, colorful paintings that make it seem like circles, triangles and squiggles are floating in illusionist space above flat surfaces painted with splatters, drips and brush marks.

James Havard - Airkara Bear's Belly, 1976. Acrylic, pastel and graphite on paper mounted on board. 40 x 31 7/8 in. (101.6 x 80.9 cm). Marian Locks Gallery, Philadelphia. Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1976. © James Havard

Reilly, too, embraced a sort of playful visual language in his work, creating sculptural paintings that seem to fly forth into space like bursts of energy in a comic book, or exploding parts of an imaginary machine dreamt up by Francis Picabia. Of these three Abstract Illusionists, Havard was the most subdued. He created somber compositions that, while still embracing the use of shadows and perspective to make it seem that elements were floating in space, also updated historic aesthetic positions like Cubism and Art Brut in contemplative ways. Looking back today at the work of these and the other protagonists of this misunderstood movement, it is easy to dismiss their efforts, since the remnants of Abstract Illusionism are scattered liberally throughout the frequently hideous popular culture of a generation ago. Call their work gimmicky, or cheesy, or trippy, or pedestrian. Call it whatever you like, but it remains legit. They were trying to re-claim depth as a formal element in painting: a serious pursuit, and one that especially in the age of COVID-19, and an overload of digital exhibitions, still has plenty of meaning for us today.

Featured image: James Havard - Flat Head River, 1976, acrylic on canvas, 72 x 96 inches. Louis K. Meisel Gallery.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio