Defining Abstract Photography

When you read the words abstract photography how do you react? Do you perk up, fascinated to discover more about this topic? Or do you recoil, annoyed at the very thought of it? Or are you ambivalent? It might surprise you to hear that how you answer this question has little to do with your imagined like or dislike of the topic itself. Rather it has to do with hidden processes in your brain. In recent years, tragically, scientists have learned much about the condition known as TBI, or Traumatic Brain Injury, mostly due to studying victims of explosions in the world’s multiple active conflict zones. One observation that has come out of their work is that victims of TBI often lose the capacity for abstract thought, which originates within a person’s frontal lobe. This realization is far from merely being academic. The ability to think abstractly can determine a human being’s ability to live a happy, successful, independent life. But it also raises fascinating questions about abstract art, and in particular abstract photography. As a medium once considered purely concrete, a debate has long raged about whether photography can also be interpreted as being abstract. Perhaps through a study of the debate the lost capacity for abstract thought could be relearned. Is it possible that we could use something like abstract photography to help someone suffering from TBI? Why not try? But since many claim that it does not even exist, first perhaps we should try to define exactly what abstract photography is.

Abstract vs. Concrete: The Basics

A simple way to understand the difference between concrete and abstract thought is to imagine saying to a child, “Good job! Want a treat?” The child would likely respond positively because it has learned that “good” and “treat” are positive words. That is concrete thinking: the ability to recognize direct associations in the present moment. But what if you said to the same child, “Good job! Would you prefer the short term joy of a food-based reward or the long term satisfaction of knowing you made good choices based on your intrinsic desire to be a responsible family member?” The blank stare you would likely receive might indicate an inability to comprehend abstract concepts such as joy and satisfaction, short and long term, family and responsibility.

When it comes to abstract and concrete concepts in art, we could say that concrete art relates only to itself. For example, a painting of a four-inch blue line titled “Four-Inch Blue Line” could be considered concrete since it objectively represents what it claims to be. But if that same painting were given a different title it might facilitate a contemplative experience for the viewer, thus becoming abstract. For example, titled “Sky” it might inspire a viewer to contemplate the general attributes of the color blue, or the nature of lines as they relate to horizons, or the meaning of words when juxtaposed with seemingly unrelated visual phenomena.

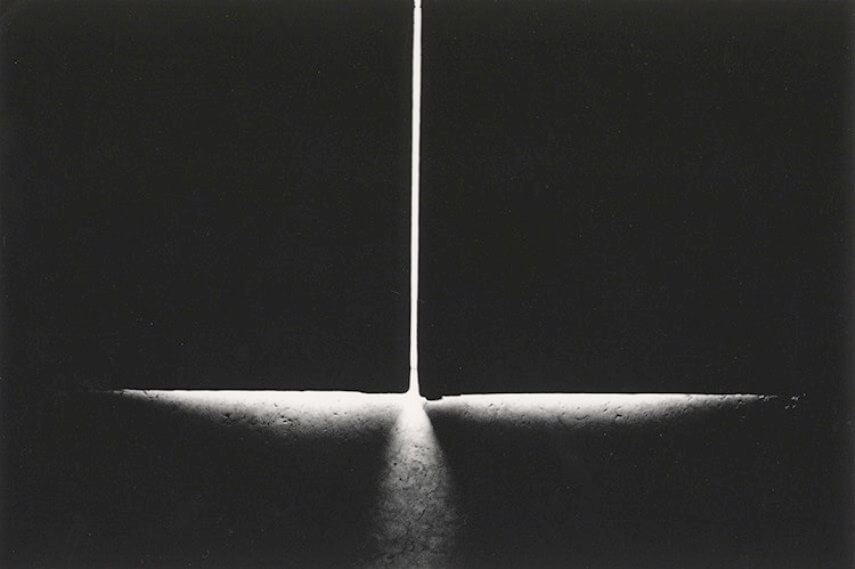

Ray Metzker - Venice, 1960. silver print, printed ca. late 1960s, 5 15/16 x 8 1/7 in. © Ray Metzker

Can Abstract Photography Exist?

Whether or not abstraction can exist in a photograph is a debate that goes back as long as abstract art itself. The debate is based on the perception that photographic technology was developed in order to capture what is plainly visible, and is therefore inherently concrete. But when we deconstruct the photographic process we realize that photography doesn’t truly capture anything. A camera simply allows marks to be made using light. What is the difference if an artist uses paint or light to draw a line?

The contemporary abstract artist Tenesh Webber uses photographic processes to create abstract images, but she does not simply aim a camera at a subject. She creates abstract compositions on Plexiglas plates using markers and string. She then layers the plates and uses them like filters to affect light as it passes through them to expose photographic paper. The resulting abstract images demonstrate that photography is really just another way of marking on a surface.

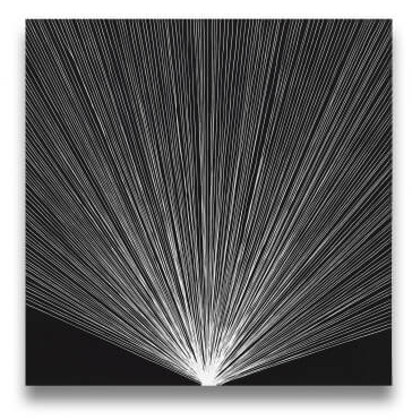

Tenesh Webber - Flash 1, 2009. Black and white photogram. 50.8 x 50.8 cm

Does Any Abstract Art Exist?

Another challenge to defining the nature of abstract photography is that there are some who question whether any art can be abstract. The artist Jean Dubuffet said, “There is no such thing as abstract art, or else all art is abstract, which amounts to the same thing.” But what Dubuffet perhaps failed to consider is what scientists call Domain Specificity. A person’s “domain” consists of their entire universe of understanding at a given moment. Our domains are informed by our experiences, our educations, our jobs, our upbringing and every cognitive phenomenon we ever experience.

Depending on a person’s domain, specificities can evoke generalities, or generalities can evoke specificities. Something concrete can seem abstract, or something abstract can seem concrete. A blue line can just be a blue line, or it can refer to all lines, or everything blue. A bookkeeper may look at a photograph of a pear and think only about what a lovely pear it is. A farmer may look at that same photograph of a pear and because of domain specificity draw larger generalizations about fruit trees, the smell of young blossoms, seasons, the connection between humans and nature, the ephemeral nature of food and subsequently of all life. To that farmer, the pear is an abstraction because of the larger generalization it represents and the undefined feelings it awakens.

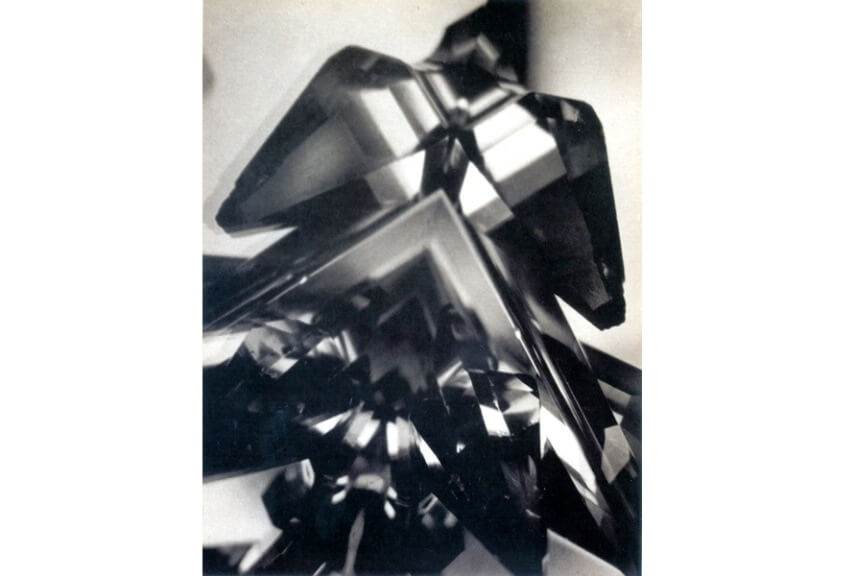

Alvin Langdon Coburn - Vortograph, 1917. Gelatin silver print. 11 1/8 x 8 3/8" (28.2 x 21.2 cm). Thomas Walther Collection. Grace M. Mayer Fund. © George Eastman House

Shadow and Light

The way photography works is through the skillful manipulation of shadow and light. Both elements are also integral to Plato’s allegory of the cave. In the allegory, people are chained to a cave wall facing another blank wall. Behind them is a fire. The people can see shadows on the opposite wall caused by objects passing in front of the fire behind them, but they cannot see what is causing the shadows. So not having seen anything but shadows their whole life they draw abstract conclusions about the nature of the forms that cause them.

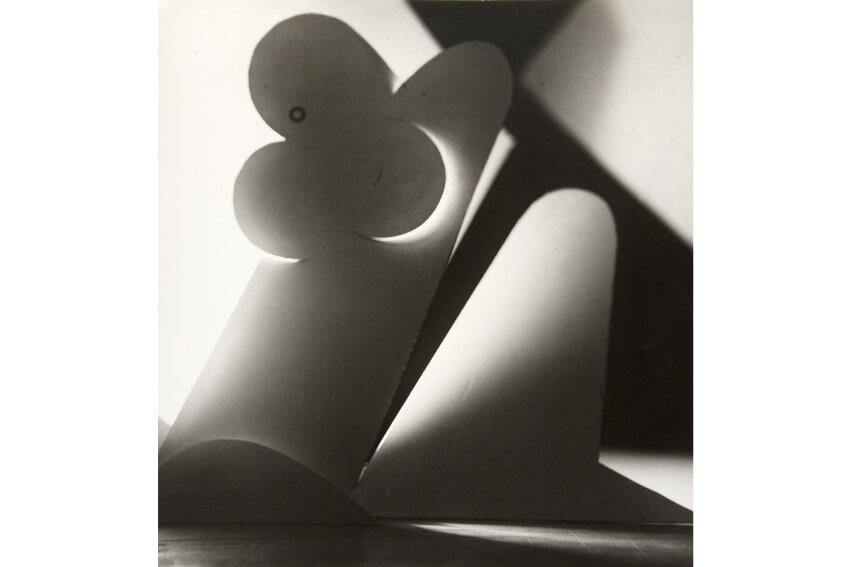

Many photographers have used these same effects to evoke abstract associations in the minds of their viewers. Jaroslav Rössler’s abstract photographs play with shadow and light to create uncanny compositions of forms that question concepts of dimensionality and space. Ray Metzker’s photographs use shadow and light to obfuscate the architecture of urban spaces. Both photographers create images that serve as starting points on an abstract thought process that questions the nature of what is seen and unseen.

Jaroslav Rössler - Akt, 1926. Gelatin silver print. 19 x 20 cm. (7.5 x 7.9 in.) © Jaroslav Rössler

Photo-Geometric Abstraction

One tried and true way to define whether a work of art is abstract is to simply trust the declaration of the artist that made it. In 1917, Alvin Langdon Coburn openly committed himself to creating abstract photography. Insisting, “an artist is a man who tries to express the inexpressible,” he embarked on a journey of creating purely abstract photographs in defiance of an art world that almost uniformly rejected the idea. In his zeal, he invented the Vortograph. Using prisms attached to the camera lens, this device created kaleidoscopic, geometric images reminiscent of Cubism, but totally abstract.

Similarly, the contemporary artist Barbara Kasten also makes what she considers to be purely abstract geometric photographs, but through an entirely different process. She constructs installations of geometric forms and surfaces, often incorporating mirrors. She then photographs the constructions resulting in images that evoke Neo-Plasticism and other abstract Modernist tendencies.

Barbara Kasten - Construct XI-A, 1981, Polaroid, 8 x 10 in. © Barbara Kasten

Larger Generalizations

Obviously from the perspective of some of us, abstract photography exists. The intent of the artist who made it and the perspective of the viewer contemplating it define it. But can it help people who suffer from conditions such as TBI? One insidious consequence of an inability to think abstractly is that it causes people to lose the ability to generalize, or to mentally construct possible chains of events in order to consider likely futures. Someone mired in concrete thinking might get hungry and walk toward the kitchen but get distracted by an ant crawling along the wall and then forget to eat altogether.

In a sense, this phenomenon is a mirror image of what happens to an abstract thinker when confronted with something like Surrealism. Surrealist photographers like Man Ray used dreamlike imagery to exploit people who are capable of making abstract generalizations. Rather than being arrested by the present, such people become arrested by the metaphysical, and the endless possible associations of say, a woman with violin holes on her naked back. Somehow the ability or lack thereof to comprehend abstract thought seems like different manifestations of the same process. If intent and perspective are at the heart of whether a photograph or any other work of art can be considered abstract, perhaps they are also at the heart of the process of retraining an injured brain. The brain is malleable, so why not? Perhaps new connections can be made. If so, as something that began as purely concrete then evolved into something that could be understood as abstract, abstract photography may be the perfect arena in which that education could begin.

Featured Image: Tenesh Webber - Mid Point #3, 2015. Black and White photogram. 11 × 11 in; 28 × 28 cm. Edition 2/5.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio