100 Years of Art and Abstract Photography at Tate

The conversation around abstract photography has gotten quite interesting in recent decades as digital photography and photo manipulation has become ubiquitous. Now a new exhibition opening in May of 2018 at the Tate promises to expand that conversation even further. Shape of Light: 100 years of Photography and Abstract Art will feature more than 300 works by more than 100 artists. It will examine the history of abstract photography in conjunction with the development of abstraction in painting and sculpture. Pure abstraction manifested widely in Western painting and sculpture around the first decade of the 20th Century. But photography was a little farther behind. Though it had nearly a century in which to develop by that time, it was still not considered really a fine art. Its sole use was perceived as a way of showing reality—a frozen moment of time burned into silver nitrate. But some of the more philosophical early photographers realized that rather than capturing images, what the photographic process really captures is light. They saw that photographers could potentially make purely abstract compositions, same as a painter or a sculptor could, using light instead of paint, wood, graphite or stone. As various photographers have experimented with different methods of achieving abstraction over the decades, they have spurred many fruitful debates about what defines a photograph, and what exactly makes any image abstract. By juxtaposing the fruits of those debates along side advancements in other types of abstract art, Shape of Light presents a fascinating opportunity to discover how at time abstract photography followed in the footsteps of painting and sculpture, and how at other times it blazed the trail.

Enter the Vortograph

One of the key turning points in the history of abstract photography occurred around the turn of the century, when two groups of photographers—known as Photo Succession and the Linked Ring—began making the case for the acceptance of photography as a fine art. Alvin Langdon Coburn was a key member of both groups. Coburn will be featured prominently in Shape of Light, because he is considered the inventor of the Vortograph—the first type of purely abstract photo. The first Vortographs were taken when Coburn attached three mirrors to the front of his camera in a triangular formation. Essentially, the mirrors acted as a kaleidoscope. The resulting photographs show a fractured reality, full of strong diagonal lines and triangular shapes. That language of line and shape led Ezra Pound to call the images Vortographs, because they resemble Vorticist paintings.

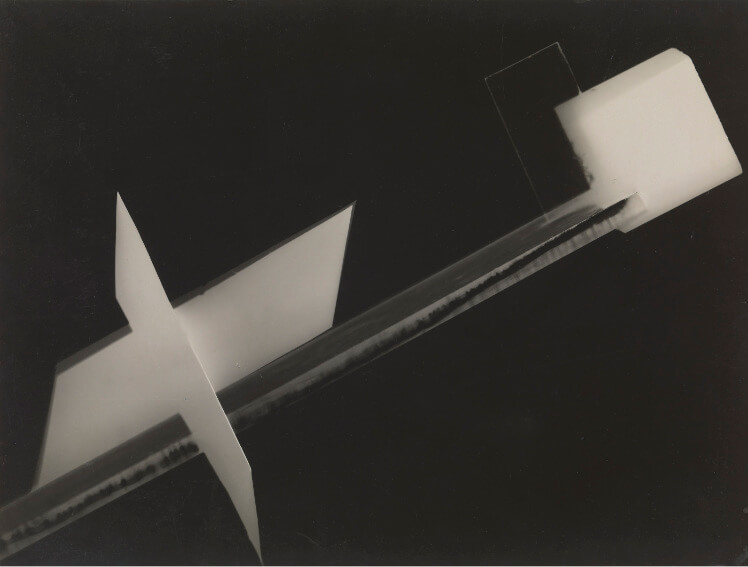

László Moholy-Nagy - Photogram, c.1925, Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper, 181 x 238 mm, Jack Kirkland Collection, Nottingham

The Tate will exhibit Vorticist paintings by artists like Wyndham Lewis along side Vortographs by Coburn. They will also be juxtaposed with works by Cubist painters, such as Georges Braque. The comparison to Cubism may already be clear, as both Cubism and Vortographs divide visual space into multiple simultaneous perspectives. But the comparison to Vorticist paintings may be a little more unclear. Vorticism was an amalgam of Cubism and Futurism. It was a purely formal attempt to combine the looks of the two. When he invented the Vortograph, Coburn was doing something wholly unique. He was not attempting to mimic trends. He was trying to prove that photography could be used to capture something other than objective reality. For this reason, Shape of Light elucidates how Coburn was much more of an innovator than his Vorticist colleagues, illuminating one way in which abstract photography lays claim to distinctive roots.

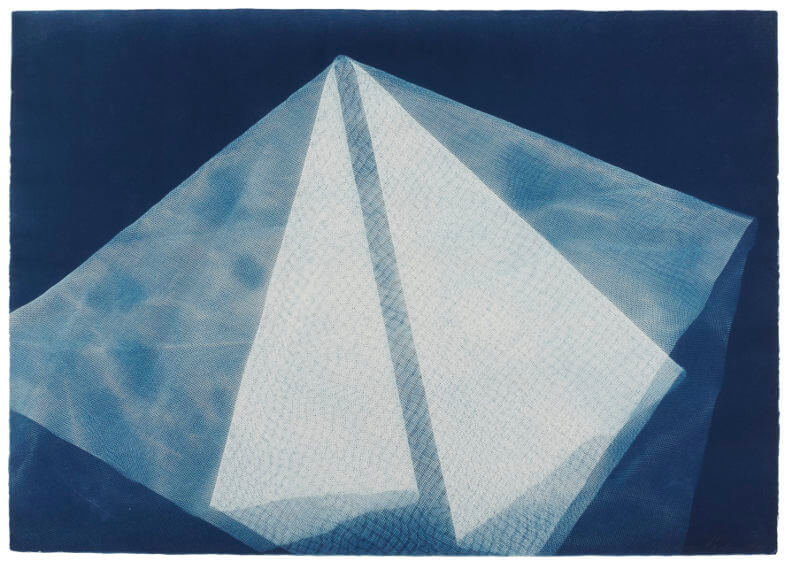

Barbara Kasten - Photogenic Painting, Untitled 74/13 (ID187), 1974, Photograph, salted paper print, 558 x 762 mm, Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Bortolami Gallery, New York, © Barbara Kasten

Abstract Photography Through the Decades

Another fascinating juxtaposition that will be offered in Shape of Light is the placement of photographs by AndreÌ Kertesz in context with the works of Surrealist painters. In 1933, Kertesz created a series of photographs called Distortions, in which mirrors were used to create twisted, elongated and biomorphic images of human bodies. The photographs share a great deal in common with the Surrealist human forms in paintings by Picasso, Miro, and others. Since the Distortions were created more than a decade into the Surrealist movement, it might seem that Kertesz was copying the Surrealists. But the first time Kertesz published a distorted photograph was actually all the way back in 1917. Titled Underwater Swimmer, that image shows a wavy, stretched out human form in an uncanny landscape. It would fit naturally in a painting by Salvador Dali. Dated three years before the start of Surrealism, it again raises questions about whether, and how, photography was actually responsible for influencing the trajectory of abstract art in general.

Shape of Light also juxtaposes the works of two Mid-Century artists: Otto Steinert and Jackson Pollock. Steinert created a diverse legacy within the world of photography, but one of his most important contributions was when he organized a group of touring exhibitions in the 1950s called Subjective Photography. The idea of the Subjective Photography exhibitions was to demonstrate that rather than capturing the outside world, a photograph was capable of expressing the inner world of the photographer. By exhibiting Luminograms by Steinert from the 1950s alongside splatter and drip paintings by Jackson Pollock, Shape of Light will demonstrate the link between the philosophy and aesthetic of Abstract Expressionism, and that of Subjective Photography. And there is much more in this exhibition as well. In addition to studying Modernist legends like László Moholy-Nagy, Bill Brandt, Guy Bourdin and Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé, it also examines many contemporary abstract photographers such as Barbara Kasten and James Welling. Showing these diverse artists in conjunction with each other is a visionary idea. It offers us not only a chance to either acquaint ourselves with, or re-examine, the history of abstract photography. It also offers a chance to shatter our pre-existing notions about what photography is, what defines abstraction, and which artists were and are truly responsible for shaping the history of abstract art.

Shape of Light: 100 years of Photography and Abstract Art will run from 2 May through 14 October 2018 at the Tate Modern, London.

Featured image: Otto Steinert - Luminogram II, 1952, Photograph, gelatin silver print on paper, 302 x 401 mm, Jack Kirkland Collection Nottingham, © Estate Otto Steinert, Museum Folkwang, Essen

By Phillip Barcio