UK's First Major Retrospective of Alberto Giacometti at Tate

Among contemporary artists, Alberto Giacometti is one of the most revered masters of all time. Though the sculptor, painter and draughtsman lived his entire life in the 20th Century, he created a body of work that is truly timeless. Alberto Giacometti sculptures pare down their subjects to the bare essentials, and yet through that simplification a sense of the vastness of their spirit is revealed. The work of few other artists is so instantaneously recognizable. And yet the opportunity to encounter a large number of Giacometti works in one place at one time is still rare. It has been two decades since there was a major Giacometti retrospective in the United Kingdom. But finally that has been corrected, as a monumental exhibition of Giacometti opened recently at the Tate Modern in London. Alberto Giacometti at the Tate Modern brings together an astonishing selection of more than 250 works, including paintings, drawings and of course sculptures, many of which have never been publicly exhibited before.

An Internationally Beloved Artist

Alberto Giacometti was born in 1901 in Borgonovo, a town in the canton of Graubünden, a region in southeastern Switzerland near the Italian border. His first art teachers were his father and his godfather, both painters, and his first artworks were portraits of his families. He is said to have completed his first oil painting at age 12, and to have made his first sculpture, of his brother Diego, at age 14. His first organized art education came at age 18 at various schools in Geneva. But in 1922, he decided to move to Paris. And that is where he would first make his name among the leading Modernist artists of his generation.

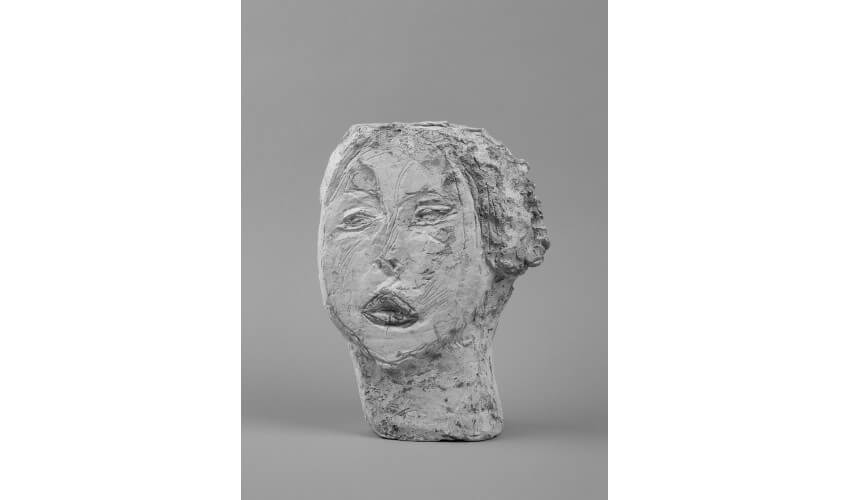

His transformation into the master we know today began while Giacometti was attending classes at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière in Paris. He studied there diligently for three years, but eventually became worn down by the exhaustion of having to copy reality. He felt drawn toward something else, and in 1925, after exhibiting for the first time at the Salon de Tuileries, he began deriving inspiration from indigenous art and movements like Cubism. So rather than copying the world, he freed himself to work from his emotions and his imagination instead. One of the first bodies of work that grew out of this change in direction was his so-called “flat sculptures,” busts with flattened forms and primitive-looking features. Some of these transformative early works, like his 1926 work Head of a Woman [Flora Mayo], are included in the current retrospective at the Tate Modern.

Alberto Giacometti - Head of Woman [Flora Mayo], 1926. Painted plaster, 31.2 x 23.2 x 8.4 cm, From the Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

Alberto Giacometti - Head of Woman [Flora Mayo], 1926. Painted plaster, 31.2 x 23.2 x 8.4 cm, From the Collection Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, Paris © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

From Surrealism to Matchboxes

Throughout the 1930s, Giacometti maintained an on-again, off-again relationship with the Surrealists. His work seemed to fit in with the Surrealist viewpoint and aesthetic, but Giacometti was never satisfied with the narrow point of view of that, or really any other organized group of artists. Nonetheless, many of the works he made during this decade that are exhibited in the current Tate retrospective, such as Woman with her Throat Cut from 1932, do evoke the mysteries of nightmares and subconscious abstraction, and speak in fascinating aesthetic conversation with Surrealist imagery.

As the 1930s wore on, Giacometti suffered a series of tragedies, including the death of his father in 1933 and the death of his sister in childbirth in 1937. Then in 1938, Giacometti was hit by a car, which gave him a limp for the rest of his life. The worst of his emotional struggle came at the start of World War II. He attempted to fight, but was turned away because of his injury. So after fleeing the German invasion of Paris in 1940 then briefly returning to the city, he finally decided to return home to Switzerland, where he remained for the rest of the war. And that is where his final transformation as an artist began. He started working on minute sculptures, so small that he was able to carry them back to paris with him after the war in matchboxes. Then, once he was back in Paris, he had an artistic epiphany inspired by his miniature sculptures and a new, entirely personal way of perceiving the human form.

Alberto Giacometti - Woman with her Throat Cut, 1932. Bronze (cast 1949), 22 x 75 x 58 cm, From the National Galleries of Scotland © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

Alberto Giacometti - Woman with her Throat Cut, 1932. Bronze (cast 1949), 22 x 75 x 58 cm, From the National Galleries of Scotland © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

The Tall and the Skinny

As could be expected, the bulk of Giacometti at the Tate Modern focuses on the extraordinary work Giacometti made after the war, after having his epiphany. For it was then that he developed his signature style of sculpting tall, elongated, skinny human forms. These remarkable figures are the culmination of a lifetime struggling to negotiate a balance between the concrete and abstract worlds. They offer a perfect figurative sentiment of the reduction of humanity felt in the aftermath of the war, and yet they contain a solidity, a concreteness, a dignity, and an agelessness that speak confidently to the eternal strength and tenacity of the spirit.

So fragile and exhausted were these figures Giacometti was creating. So powerful in their presence they were, and yet so delicate. In 1948, Giacometti had his art exhibited in the United States for the first time, at the Pierre Matisse Gallery, which was owned by the youngest son of the artist Henri Matisse. The catalogue essay for the exhibition, which was titled A Quest for the Absolute, was written by a French writer whom Giacometti had befriended just before the war, named Jean-Paul Sartre. Over the next decade and a half, the public fascination with these astonishing works brought Giacometti international fame. He exhibited multiple times at the Venice Biennale, as a representative of France, was included in exhibitions throughout Europe, as well as in his home country, and was given retrospectives in Germany, the United States and England.

A Return to the Tate

Giacometti died in 1966, in the Alpine city of Chur, in the same region where he was born. And he is buried in his hometown cemetery. There is no question that he is revered by the people of his home country. But at the same time he is most often associated with France, where he lived when he did much of his most important work. Just before his death he was even honored by the nation of France with the National Arts Award, a testament to the impact on that country of his life and his art. Nonetheless, it is also worth mentioning that the last retrospective Giacometti had while he was still alive was actually in England, and like the current retrospective also happened to be at the Tate, then called the Tate Gallery. That exhibition, which was held in 1965, also traveled to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Louisiana Museum in Humlebaek, Denmark.

Annette Giacometti, the wife and frequent model of Alberto, lived another 27 years after her husband died, and devoted en enormous amount of her time and energy to preserving the legacy of her husband. She set up a foundation to document and collect his works, and was instrumental in ensuring good scholarship of his life. In fact, it is through a previously unequalled access to the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti in Paris that this current Giacometti exhibition at the Tate modern is able to bring together such an extraordinary collection of rarely seen, and never-before seen works. Alberto Giacometti at the Tate Modern in London will be on view until 10 September 2017. The exhibition is curated by Frances Morris, Director of the Tate Modern in conjunction with Catherine Grenier, Director and Chief Curator of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti in Paris, along with Lena Fritsch, Assistant Curator at the Tate Modern and Mathilde Lecuyer, Associate Curator of the Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti. Accompanying the exhibition is a complete catalogue produced by Tate Publishing, which is co-edited by the curators Frances Morris, Lena Fritsch, Catherine Grenier and Mathilde Lecuyer.

Alberto Giacometti - The Hand, 1947. Bronze (cast 1947-49), 57 x 72 x 3.5 cm, from the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

Alberto Giacometti - The Hand, 1947. Bronze (cast 1947-49), 57 x 72 x 3.5 cm, from the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich, Alberto Giacometti Stiftung © Alberto Giacometti Estate, ACS/DACS, 2017

Featured image: Alberto Giacometti and his sculptures at the Venice Biennale, 1956, from the Archives of the Giacometti Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio