A New Book Celebrates Alice Trumbull Mason, Pioneer of American Abstraction

Alice Trumbull Mason was a rarity in the art field: a die hard practitioner motivated entirely by the desire to learn. Mason died in 1971, at age 67, leaving behind hundreds of paintings and prints that place her among the most prescient and talented artists of her time. Immune to trends, and unceasingly devoted to experimentation, she created a body of work that transcends time. A major monograph documenting more than 150 of her paintings, and featuring insightful essays about Mason by contemporary art writers such as Elisa Wouk Almino of Hyperallergic, is forthcoming from Rizzoli Electa publishers in New York (it can be pre-ordered now). The most complete assessment of her career to date, it will be prized for its beautiful, full-page reproductions of so many of her works. Yet, the reception the book is already getting is a bit strange. The strangeness is embodied by the headline of a recent review written by Roberta Smith for the New York Times, which calls Mason a “Forgotten Modernist.” That claim, that Mason was not appreciated during her time, or has been ignored since her death, is less fact, and more hyperbole to feed the art market appetite for works and artists that have supposedly been “overlooked.” I reject it as a theory in this case only because I know too many actual artists who exist in the real art field. Most artists would love to have the career Alice Trumbull Mason had. Over four decades, she had six solo shows in New York City, co-founded American Abstract Artists, befriended and learned from several of the most highly regarded artists of her time, and sold works to some of the most influential figures in the art world, including Hilla Rebay and Peggy Guggenheim. In a reality where the overwhelming majority of artists never have a single New York solo show, and never sell any paintings at all, Mason was a smashing success. Rather than letting the art market warp her legacy to fit its corrupt narrative, we should pay respect to what Mason actually did.

A Personal History of Art

One testament to the kind of artist Alice Trumbull Mason was can be found in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, where her personal papers were donated. The collection includes a notebook, on the cover of which Mason hand wrote “History of Art.” Inside its pages (which are available to browse online) are personal reflections about the lives and artworks of a couple dozen classical masters. Instead of reading and regurgitating art history, Mason went to Europe and personally visited influential works, taking time to also learn about the humans who made them. Her personal art history book includes both plastic observations and insights about the inner lives of the artists. Both are equally revealing. For example, she notes that Michelangelo did not want to paint the Sistine Chapel, and that he resented many of his other patrons as well. The fact that he became one of the most famous artists ever was irrelevant to Mason—she was more interested in the fact that he was unhappy because he did not have the freedom to paint what he wanted.

Alice Trumbull Mason - #1 Towards a Paradox, 1969. Oil on canvas. 19 x 22 in (48.3 x 55.9 cm). Washburn Gallery, New York.

On the subject of the plasticity of art, Mason takes note of a quote by the Renaissance sculptor Donatello, who said, “You lose the substance for the shadow.” In his case, Donatello was speaking about the effects of bold changes in lightness and darkness, known as chiaroscuro. Though the details of a figure may be lost when light hits the folds of a sculpted fabric, or the ridges of sculpted muscles, drama and realism emerge from the perceived sense of depth the shadow creates. Mason read something even more profound in his words. She saw in this quote a reference to the potentiality of abstraction. The shadow became a metaphor for the unknown. Just as the unknown made a sculpture seem real to Donatello, the unknown represented what was most real for Mason. She considered abstract art to be the most representative kind of art—it was the unknown, instead of the known, that she was working to represent.

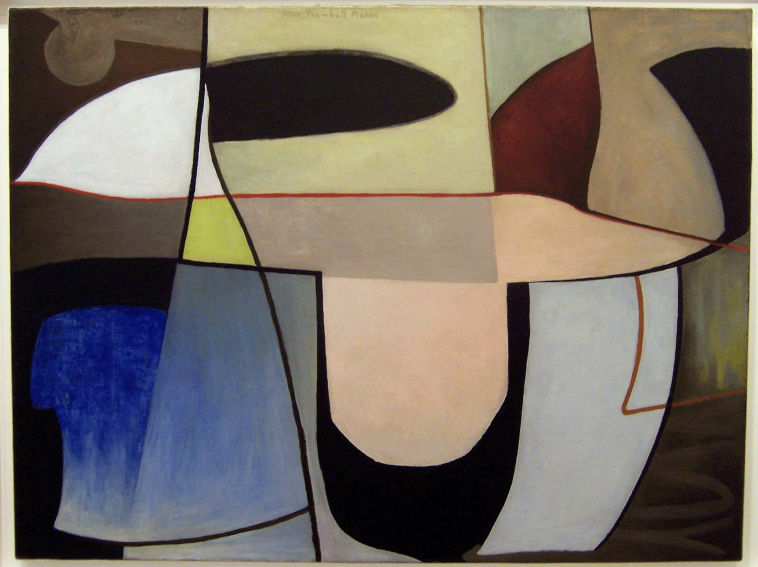

Alice Trumbull Mason - Untitled, ca. 1939. Oil on canvas. 30 x 40 in (76.2 x 101.6 cm). Washburn Gallery, New York.

A Total Pioneer

The title of the forthcoming Mason monograph—Alice Trumbull Mason: Pioneer of American Abstraction—could not be more fitting. For me, it recalls the old American adage from the early days of western expansion: “Pioneers get slaughtered; settlers get rich.” Art may never have made Mason a fortune, but what you find within the pages of this monograph is evidence of an artist who never settled. As early as 1929, when she was 25 years old, Mason was devoted to the secular spiritual possibilities contained with abstract art. She happily studied conflicting theories, fluctuating between the lyrical biomorphism of artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Joan Miro, and one of her personal mentors, Arshile Gorky, and the geometric, plastic purity of artists like Piet Mondrian. She oscillated between these two positions throughout her life. In 1945, when Hilla Rebay mounted The Kandinsky Memorial Exhibition, which featured 227 paintings, Mason wrote a personal letter to Rebay thanking her for providing her the chance “to study so fully” so much of his work in person. Yet, only one year later, Mason was already adding rectangles, and what she called “architectural” structure, to her compositions in the Neo-Plastic spirit of Mondrian.

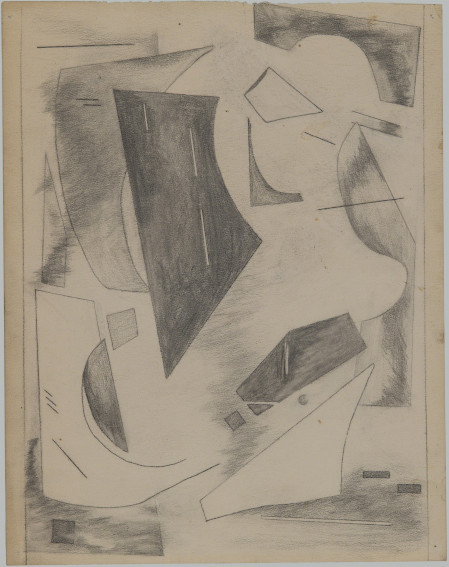

Alice Trumbull Mason - Drawing for "Colorstructive Abstraction", 1947. Oil on masonite. 26 1/2 x 23 in (67.3 x 58.4 cm). Washburn Gallery, New York.

Ultimately, Mason held true to two guiding principles in her work that over shadowed any superficial concerns about content. The first was her belief—whether she was making paintings or prints, biomorphic compositions or geometric ones—in the importance of personal freedom when it comes to what art to create, and how to create it. And the second was her awareness that the medium itself the most important and expressive element of abstract art. Like all great artists, the magic of her work is not in her exhibition CV, nor her auction prices, nor in how many contemporary collectors now know her name—it is in the ekphrastic plasticity of the paint itself.

Featured image: Alice Trumbull Mason - Staff, Distaff and Rod, 1952. Oil on canvas. 34 3/8 x 42 in (87.3 x 106.7 cm). Washburn Gallery, New York.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio