How Alma Thomas Fought Many Wars To Establish Herself

In 1972, at the age of 80, Alma Thomas earned the distinction of becoming the first African American woman to have a solo retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Her colorful, abstract unlike anything being done at the time by her contemporaries, and were received by the public as a revelation. In his review of the exhibition in The New Yorker, famed art critic Harold Rosenberg wrote that Thomas brought joy to the 70s. Amazingly, Thomas had only been a full time artist for 12 years when he work was featured in that exhibition, and she had only been painting in her signature abstract style for eight. She had fought many battles to arrive at this wondrously unexpected position: socio-political battles of racial segregation and gender biases in education; aesthetic battles between two and three-dimensional art, figuration and abstraction; the battle of educating and guiding the younger generation, both at her job as a teacher and as an active member of her community; and not least of all, she had fought the battle of her own aging body after delaying her professional goals until her retirement after 35 years of teaching at Shaw Junior High School, a public school in Washington, DC. Ironically, it was that last battle, the one with her aging body, that led Thomas to discover her mature aesthetic voice. For decades while teaching, she had been dabbling in architecture, sculpture, and figurative painting. After retiring, she began exploring abstraction, but had trouble arriving at a position of comfort with her abstract method. In 1964, after she suffered a debilitating bout of arthritis, she set out to develop a new method. Sitting down in front of a window in her two-story brick town-home and looking out at a tree, she instinctively transformed what she saw into dashes of colorful pigment, creating a style that is now instantly recognizable as that of the late blooming genius, Alma Thomas.

Fighting for Love

When Alma Thomas was born in Columbus, Georgia, on the border of eastern Alabama, in 1891, it was the heart of the segregated American south. Throughout her youth, she found herself torn between two simultaneous realities. At home, her parents raised her to read classic literature, study languages, and pursue knowledge of the arts. Meanwhile, all around her in the public, the dominant, racist, white culture treated her as if it was only by its grace alone that she was even allowed to exist. In the midst of this confusing dichotomy, Thomas fought for moments of peace and harmony. She most frequently found such moments in nature. Her grandfather co-owned a massive plantation in Alabama with his white half-brother. On visits there, Thomas absorbed powerful lessons about the beauty of the land, and about the love that can exist between people of all backgrounds when we work together.

Alma Thomas - Atmospheric Effects II, 1971. Watercolor on paper. 22 1/8 x 30 1/4 in (56.2 x 76.8 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of Vincent Melzac, 1976.140.4

Ultimately, her parents moved Thomas and her siblings north to Washington, DC, where Thomas was able to enroll at Howard University, a historically black college. Although her race was no longer holding her back, she still had to fight another battle—against gender biases. Thomas wanted to study architecture, but was discouraged because she was a woman. She enrolled in home economics classes, but was soon asked by James Herring, the founder of the new art department, to enroll in his classes. Thomas switched her major to art, and in 1924 became the first student to graduate from the Howard Fine Arts Department. Even though she may not have originally wanted to pursue the life of an artist, or a teacher, she found in that profession a true calling. As she told Eleanor Munro in an interview for the Washington Post just months before Thomas died, “Even after I retired in 1960, I devoted my time to the children who lived nearby. Rounding my neighborhood were the slums of the world. On Sundays those children would be running up and down the alley. So I got them to clean up and come to my house and we made marionettes and put on plays.”

Alma Thomas - Yellow and Blue, 1959. Oil on canvas. 28" x 40". Michael Rosenfeld Gallery.

Fighting for Style

Like many female artists, and many artists of color, Thomas frequently found herself being described not as an artist, but as a female artist, or a Black artist. She resented this distinction, because she felt it diminished her. She had left segregation behind, and rejected any insinuation that somehow her accomplishments need to be judged separately from those of her white and male colleagues. Thomas also rejected the notion that she had to paint subject matter that was specific to her personal identity. She sought to understand what about her vision was universal. She recalled being a child and digging up samples of the multi-colored clay from a river on that Alabama plantation her grandfather owned. When she looked at the trees outside the window of her town-home window, the colors were there again. When she watched the astronauts on television traveling into the heavens, she saw the colors again in the explosions of fuel beneath their rockets.

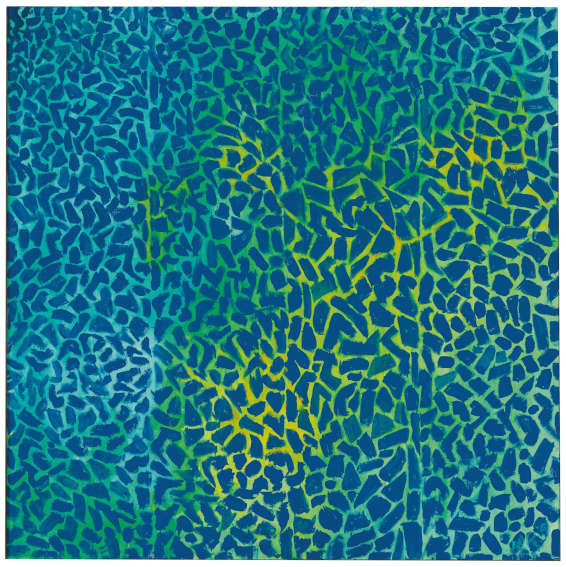

Alma Thomas - Lake Reflecting Advent of Spring, 1973. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 45 in (114.3 x 114.3 cm). Estate of Joseph H. Hirshhorn, New York and Washington, D.C. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, gifted from the above. Acquired from the above by the present owner, 1996.

She saw color and light everywhere, and recognized in their ubiquitous beauty a source of meaning to all humans. “Through color,” she said, “I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness.” This aspirational decision was not without controversy, however, as it is still not without controversy now. But Thomas believed firmly that in the universal aspects of abstract art, the deepest truths of the human condition may be revealed. The lasting legacy of her paintings is evidence enough that Thomas was correct. More than 40 years after her death, her colorful canvases declare they were created by a careful, thoughtful, experienced visionary. They are luminous, offering an enduring light against the ignorance Thomas fought against throughout her life. They are beautiful, and in their beauty present a battlecry against any who would deny abstraction. Most importantly, they are masterful, and in their mastery present an undeniable tribute to the wisdom and the triumph of her being.

Featured image: Alma Thomas - Untitled, 1968. Acrylic and pressure-sensitive tape on cut-and-stapled paper. 19 1/8 x 51 1/2" (48.6 x 130.8 cm). Gift of Donald B. Marron. MoMA Collection.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio