How Analytical Cubism Prefigured Pure Abstraction

What seem like opposite forces in the world actually compliment each other. So it was in the turn of the 20th Century between two major, simultaneous trends in the world of art: analytical cubism and pure abstraction. On the one side were the artists associated with analytical cubism, famous names such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, geniuses dedicated to discovering a conceptually hyper-realistic way of making art. On the other side were the artists associated with pure abstraction; folks such as Wassily Kandinsky, who were dedicated to discovering a completely non-representational art. Though apparently diametrically opposed, these two different approaches to art making were inextricably linked. By breaking apart objective reality in order to present it more fully, the analytical cubists helped pure abstraction find its voice.

What Was Analytical Cubism?

When art critics and art historians talk about analytical cubism, they’re referring to a tendency in painting that arose between 1908 and 1912. Prior to that time, paintings had been seen as either two-dimensional (if lacking depth) or three-dimensional (if given a sense of depth through techniques like shading). During that time, a small group of artists led by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque engaged in revolutionary aesthetic experiments intended to take painting into the fourth dimension.

The old ways of painting relied on an artist working from a single perspective. While that was suitable to show a momentary image of a subject, it did not achieve what Picasso considered to be reality, which was perceived from multiple perspectives at once. In order to achieve a sense of movement and time passing (the 4th dimension), Picasso and his colleague Braque abandoned the use of the single perspective. Their argument was that in real like we perceive objects from a multitude of different perspectives. We see something from different points of view at different times of day in different lighting, sometimes moving and sometimes standing still. Their experiments endeavored to show their subject matter in this more realistic way, from a multitude of different viewpoints all at the same time.

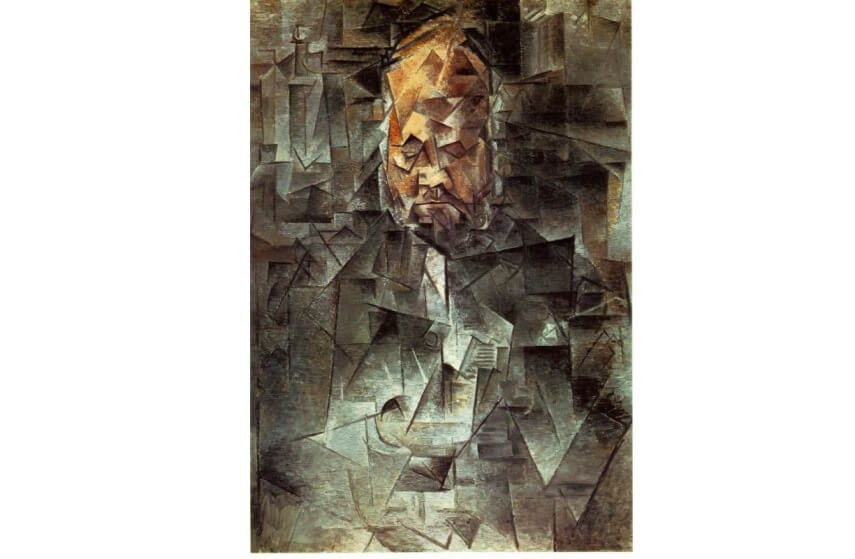

Pablo Picasso - Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, 1910, Oil on canvas. 93 x 66 cm, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow, © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Simultaneity

Their word for this type of multiple perspective painting was simultaneity. They painted bits of their subject matter from different points of view and in different lighting and at different times of day and then combined those bits onto a single plane, showing all of the different view points at once and without giving special preference to any of them. In order to heighten this effect, they kept their color palette simple and avoided shading or any other technique that would add depth to the picture. The result was a flattened, multi-view image seemingly composed of simplified geometric shapes.

To a casual observer, an analytical cubist painting might seem abstracted. But truly analytical cubism was not abstraction; it was rather a form of heightened realism. The result of Picasso and Braque’s experiments was, in their mind, a more realistic representation of their subject matter, at least from a conceptual standpoint if not a literal one. One of the earliest examples of what we now call analytical cubism is Picasso’s Portrait of Ambroise Vollard, painted in 1909. In it, we can clearly see that the subject matter is intended to be representational, while the different points of view, different lighting and different planes give us a sense of movement and simultaneity that heighten our understanding of the subject’s presence.

Wassily Kandinsky - The Cow, 1910, Oil on canvas, 95.5 cm x 105 cm

Meanwhile in Munich

The same year Picasso painted his Portrait of Ambroise Vollard in Paris, Wassily Kandinsky, the artist who would soon be credited with the invention of pure abstraction, was in Germany conducting his own aesthetic experiments. Kandinsky was also working with the idea of flatness and simplification of the aesthetic vocabulary, but for different reasons than Picasso and Braque. Kandinsky was on a mission to create completely abstract paintings. He believed that, as with instrumental music, visual art could have the capacity to communicate deeper emotions and perhaps a sense of spirituality by communicating on a purely abstract level.

Kandinsky’s experiments were an extension and culmination of many different trends that had been occurring in art since the mid-1800s. He was breaking down painting into its essential elements, such as color, line and form, and learning what each of those elements might communicate on its own. He believed that these elements might be compared to different musical notes, keys or tempos in the sense of the effect they could have on the human psyche. An example of Kandinsky’s work from this time is his painting The Cow, which, although clearly representational, achieves a flattening of space and a radical deconstruction of the aesthetic elements of the picture.

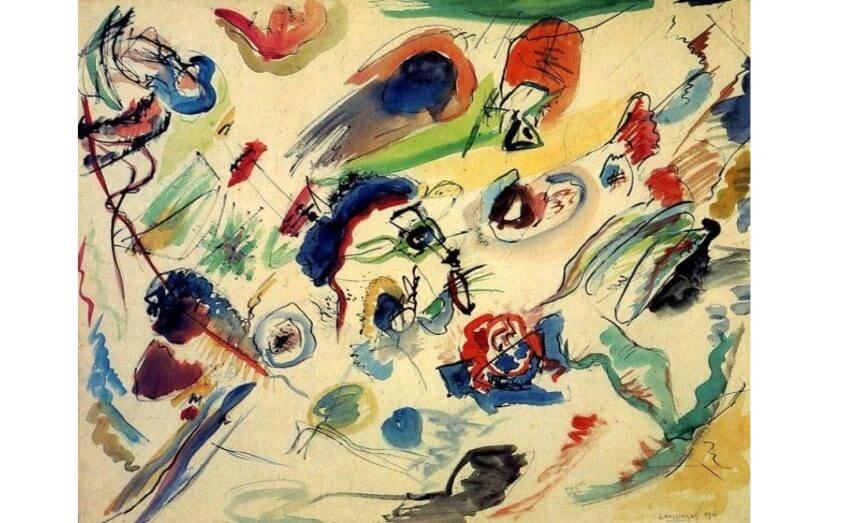

Wassily Kandinsky - Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor), 1910, Watercolor and Indian ink and pencil on paper, 49.6 × 64.8 cm, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

Worlds Combine

So in France, Picasso and Braque were flattening their images and reducing their aesthetic vocabulary, so that they could effectively portray their subject in a simplified way from multiple different vantage points. And in Germany, Kandinsky was also striving for flatness and two-dimensionality, and was also simplifying his imagery, but for a different reason. Rather than using geometric shapes to enhance a viewer’s understanding of a painting’s subject, Kandinsky and others of his mindset to explore what meanings may be gleaned from geometric shapes if used independently of representative subject matter.

Someone who was unaware of the purpose of the artists’ different experiments might see one or the other of their paintings and come away with a much different concept than that which was actually intended. But these two different schools of thought were nonetheless quite opposite in their intent. The same year that he painted The Cow, Kandinsky had a break through. He combined his own theories about instinct, spirituality and color with the analytical cubists theories about flatness and geometric simplification and created what most historians now consider to be the first purely abstract painting: Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor).

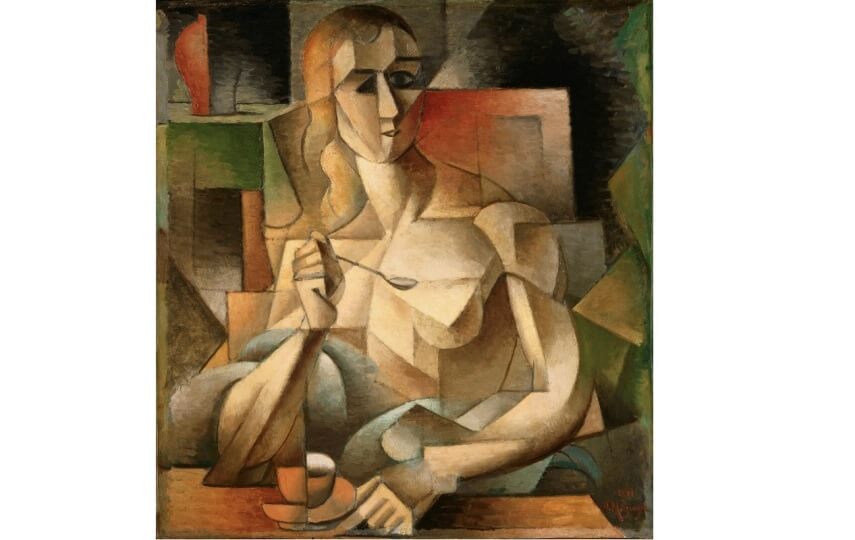

Jean Metzinger - Tea Time, 1911, Oil on cardboard, 75.9 x 70.2 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection, 1950, Philadelphia

Multiple Contemporaneous Simultaneities

It’s funny today to imagine the stir caused by Kandinsky’s Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor) and Picasso and Braque’s analytical cubist paintings, and the feeling so many painters must have had that they needed to take sides. For the next couple of years, a slew of other painters took up analytical cubism, and along with Picasso and Braque continued to explore the fourth dimension in their works. In some cases, their paintings became more and more simplified, demonstrating a clear vision of precisely what analytical cubism was all about. For example, the painter Jean Metzinger’s Tea Time, which is considered to be a particularly direct, perhaps rather obvious example of analytical cubism’s intent. It demonstrates simultaneity effectively while relying on a limited number of different perspectives.

Other analytical cubists were making work that went the other direction, becoming more dense and more complex, making it increasingly difficult to make out the subject matter. One example is Pablo Picasso’s Accordionist, painted in 1911. Though Picasso was not intending for this to be an abstract painting, many viewers to this day misunderstand this work and consider it to be abstract simply because it’s hard to make out what’s being represented; especially in light of so many other painters who intentionally were trying to make abstract work at the same time.

Pablo Picasso Accordionist, 1911, Oil on canvas, 130.2 x 89.5 cm,Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Does Intention Really Matter?

It has often been noted that when reading a poem, the effect changes if you happen to personally know the poet. The same could easily be said about a painting, or a piece of music, or perhaps any work of art. Even though the analytical cubists were not intending to contribute to the rise of purely abstract art, the casual viewer who did not know them personally, and who knew nothing of the theory behind their work, no doubt had reactions to the work that had no correlation with the artists’ intentions.

Whether it was their intent or not, the analytical cubists helped the pure abstractionists by preparing the public, including critics and historians, to accept experimentation with structure and perspective. Their work seemed non-representational, though it nonetheless contained subject matter, so in addition to whatever the analytical cubists intended for viewers to feel, they also felt other things, on a subconscious level. That contribution of helping viewers to contextualize subconscious emotional reactions to seemingly non-representational imagery was the most vital contribution analytical cubism made to the evolution of pure abstraction.

Yes, analytical cubism and pure abstraction were opposite forces in terms of intention. But by challenging the pictorial plane and distorting the public’s sense of representational reality, analytical cubism complemented pure abstraction and helped it gain acceptance in the public realm. Though seemingly opposed, these two radically different ways of approaching art contributed much to each other’s success.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio