Arthur Dove, One of America’s Greatest Painters

Oct 24, 2018

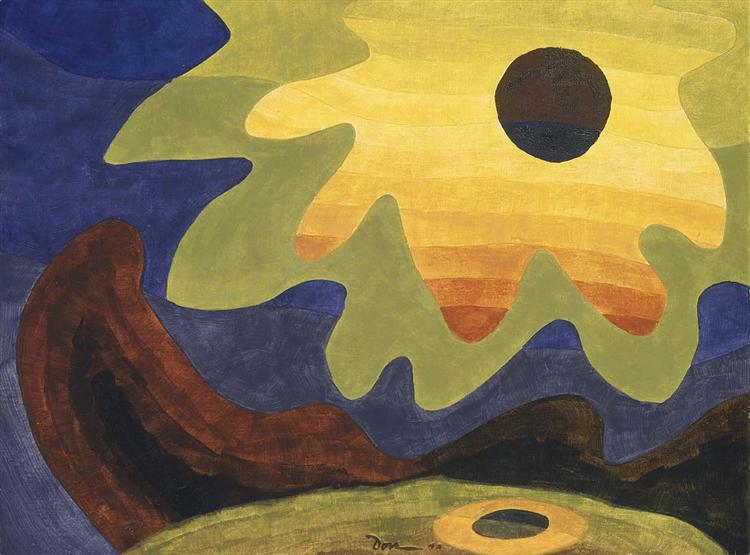

The name Arthur Dove may not be as well known today as the name Georgia O’Keeffe, but the two painters and their oeuvres share a great deal in common. Both were on the forefront of early 20th Century American abstraction, and both were championed by Alfred Steiglitz, owner of the famous 291 Gallery in New York. The earliest abstract works O’Keeffe made date to around 1915. For that reason, Dove often receives the credit for being the “first” American abstract painter. He had his first exhibition of what he described as abstract works in 1912. However, there is some question today whether those works should truly be considered abstract. The exhibition, titled “The Ten Commandments,” featured paintings that by contemporary standards of were probably figurative. They were titled after real world subject matter and the content clearly referenced objective reality. For example, one of the most well-known paintings from the show, “Sails” (1911), clearly features forms that look exactly like boat sails. On the contrary, the charcoal abstractions O’Keeffe made a few years later were what could more accurately be called “pure abstraction,” meaning they did not reference something concrete. In any case, the real take-away here is not whether Dove or O’Keeffe deserve bragging rights for being the “first” American abstract artist. Whatever you call his work, the point is Dove deserves more recognition than he currently receives. He was a true American abstract pioneer, if for no other reason than the fact that he saw abstraction as more than just a style—he saw it as a process.

Extraction, Not Abstraction

If you refer to his own words, it seems that perhaps Dove himself was not exactly sure if he was an abstract painter or not. He once said, “I look at nature, I see myself. Paintings are mirrors, so is nature.” This quote indicates that he was trying to convey something truthful and accurate about what he saw in the natural world. Yet he also once said, “I would like to make something that is real in itself that does not remind anyone of any other things, and that does not have to be explained.” This idea sounds much more like that of an artist who is striving for abstraction. Ultimately, Dove found his comfort zone in a middle ground theory he called “extraction.” Whereas abstraction could be seen as a path towards non-objective painting, Dove viewed “extraction” as a way of extracting the essence of his real-world subjects and translating it into a reduced world of forms, colors, shapes and line.

Arthur Dove - Nature Symbolized, 1911

One way of thinking about “extraction abstraction” is in the context of the philosophies of the transcendentalist movement. Like the author Henry David Thoreau, Dove was troubled by the industrial growth that the world was experiencing during his lifetime. He sought solace in nature, but also like Thoreau he did not want to simply imitate the artistic techniques of the past—he wanted to do something modern. Dove finally found inspiration in 1907 when he had the chance to live for two years in France. There, he discovered the works of the fauvist painters, which helped him understand how non-objective techniques could be used to reveal the truth. He saw that although Fauvist colors were not realistic, they conveyed perhaps an even more accurate feeling about the subject of the painting. When he returned to the United States in 1909, Dove was armed with the sense that he could use non-objective techniques to extract the truth of the things he wanted to paint.

Arthur Dove - Goat, 1934

What Makes An American

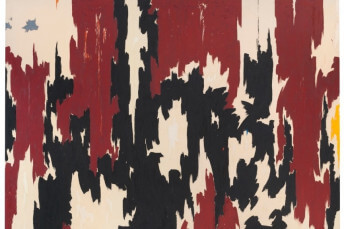

Considering the poetic, bohemian attitude Dove had, it is a surprise to many people when they find out that he was actually born into a wealthy family. In fact, he was given an Ivy League education in hopes that he would follow his father into the business world. Instead, he followed in the footsteps of a family friend from childhood—an older painter who let him take his canvas scraps to paint on when he was a child. In college, Dove took illustration classes, and found work after graduation in New York illustrating magazines like The Saturday Evening Post. His parents were furious and cut him off financially. To make matters worse, Dove became bored with illustrating and gave it up in order to pursue his artistic ideal. It was his relationship with Steiglitz that saved him. Not only did the emotional support of a believer encourage the painter, but Steiglitz also introduced the work of Dove to the wealthy collector Duncan Phillips, the founder of the famous Phillips Collection of art. Duncan took an immediate liking to the work and gave Dove a modest stipend each month in exchange for the right to have first chance to buy any new work that he showed.

Arthur Dove - Sun, 1943

Perhaps there is an argument to made that his patron is what defines Dove as a great American painter. What could be more American after all than being funded by the wealthy heir of a banking and industrial magnate? Dove himself had some thoughts on this subject. He said, “What constitutes American painting? It is what is in the artist that counts. What do we call American outside of painting? Inventiveness, restlessness, speed, change.” But I am not sure that Dove fit even his own standard definition of American-ness. He was inventive and he advocated for change, yes, but he certainly did not embody speed, nor restlessness. My argument for Dove as an important American painter is that, like O’Keeffe, he embodied qualities that are more subtly connected to the American psyche. “Extraction Abstraction” is a distinctly non-materialistic tradition. It represents the American alter ego championed by Walt Whitman and Aldo Leopold—which recognizes abstraction not as a style based on something superficial, but as a lifelong process with its roots in the mind.

Featured image: Arthur Dove - Foghorns, 1929

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio