When Georgia O'Keeffe Created Abstract Art

It is a challenge when interacting with art to ignore the clichés, allegories and judgments heaped upon it by others, and to simply come at it with an open mind. This is particularly difficult with Georgia O’Keeffe art. In her 98 years of life, O’Keeffe created one of the most famous, beloved, and instantly recognizable oeuvres in the history of American art. Examples of her work are in most major American museums. Her paintings, drawings and sculptures have been dissected by every major critic of the past century, and have formed the basis for books and university courses. And yet, when asked to speak about Georgia O’Keeffe art, many of us lazily propagate a limited range of strikingly similar perspectives: that O’Keeffe was a decorative artist who loved the American Southwest; that she was a figurative painter whose most famous images are of flowers; and that those iconic flower paintings are actually secret pictures of vaginas. Back in 2009, the Whitney Museum in New York attempted to undermine those played-out notions by hosting the exhibition Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction. The show featured 125 abstract works by O’Keeffe that together made the case that this essential American artist has been monumentally misunderstood. But despite the success of the Whitney exhibition and the subsequent critical re-visitation her work has received, Georgia O’Keeffe is still largely referred to as a figurative painter, and still burdened with metaphors and clichés about her work. People continue to talk about what her paintings are of, instead of how they make one feel. If we ever want to more fully grasp her vision, and to understand her indispensable contribution to contemporary art, we must keep an open mind and take a deeper look at what Georgia O’Keeffe accomplished as an abstract pioneer.

An American Proto-Abstractionist

Whether traced back to the work of Hilma af Klint, the 19th Century Swedish mystic painter, Post-Impressionist painters like Georges Seurat, or visionaries like Wassily Kandinsky and Kazimir Malevich, the modern history of abstract art is almost always said to have begun in either Europe or Russia. But evidence exists that Wisconsin-born Georgia O’Keeffe deserves equal billing with those innovators. The first abstract artworks we have by O’Keeffe were made at least as early as 1915, the same year Malevich painted Black Square and only two years after Kandinsky painted his first abstract works. But her intellectual grasp of the potential abstraction has to communicate the unknown is the main reason O’Keeffe deserves equal credit for inventing modern abstract art.

Like Klint, Seurat, Kandinsky and Malevich, O’Keeffe approached her work with a philosophical reverence. She understood art to be more than simply the making of images and objects. The artist considered it a potential avenue toward the expression of something more profound. Like Kandinsky, O’Keeffe spoke about the ability music has to abstractly communicate profundities. She said, “Singing has always seemed to me the most perfect means of expression. It is so spontaneous. And after singing, I think the violin. Since I cannot sing, I paint.” But whereas Kandinsky turned to abstraction in hopes of expressing something spiritual and universal, O’Keeffe was trying to express something more, you might say, American. She was trying to express herself.

Georgia O'Keeffe - Abstraction White Rose, 1927 (Left) and Georgia O'Keeffe - Music Pink And Blue II, 1927 (Right), © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe - Abstraction White Rose, 1927 (Left) and Georgia O'Keeffe - Music Pink And Blue II, 1927 (Right), © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Those Are Not Flowers

The earliest abstract artworks made by Georgia O’Keeffe were simple, elegant compositions made with charcoal on paper. The images evoke the biomorphic forms and patterns found in nature. But rather than attempting to portray her subject matter directly in these drawings, she focused purely on formal elements like line, shape, brushstroke, gesture, and balance. One of the great stories about these charcoal drawings is that they could have easily been lost to history if it were not for the devious act of a friend. O’Keeffe shared the drawings with that friend, who then went on to show them, without permission, to Alfred Stieglitz, the owner of 291 Gallery in Manhattan. Stieglitz recognized the obvious beauty and striking modernity of the drawings and immediately decided to exhibit them in his renowned space. And so began the professional art career of Georgia O’Keeffe.

Shortly after first exhibiting with Stieglitz, O’Keeffe moved to New York. For the next decade or so, she prolifically expanded her exploration of abstraction. She continued making work that echoed the aesthetic elements and compositions she perceived in nature, and went far beyond her initial charcoal drawings to develop an advanced intuition for color relationships. Her use of color vastly heightened the expressive power of her paintings. But as for what specifically she was trying to express, that is where a common misunderstanding of her work asserts itself. So many of the images she made during this time seem like nothing but blown up fragments of flowers. Or they at least seem to speak in direct conversation with the aesthetic qualities of flowers. And perhaps they do indeed communicate something that is also communicated by flowers. But they also communicate something more. As O’Keeffe said, “I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn't say any other way - things I had no words for. I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at - not copy it.”

Georgia O'Keeffe - Flower of Life (Left) and Georgia O'Keeffe - Flower of Life II (Right), © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe - Flower of Life (Left) and Georgia O'Keeffe - Flower of Life II (Right), © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

A True Pioneer

Around the 1930s, after a decade and a half of focusing on abstract imagery, O’Keeffe began to explore a broader range of styles and influences. She painted figuratively for a number of years then returned back to abstraction, then fluctuated back and forth, often calling into question the difference between the two approaches. In her later years, she sometimes seemed to be directly painting the landscapes and natural objects that surrounded her New Mexico home, for which she eventually left New York. But the essence of her work always remained the same. Her aim was always to communicate a feeling, to capture how she felt by using nature as inspiration, not to paint decorative images of nature as it objectively appeared.

In her lifelong quest to communicate feeling, O’Keeffe innovated many important aesthetic investigations. She demonstrated an interest in all-over abstract compositions, placing equal importance on all areas of the picture plane, long before Clement Greenburg attributed that accomplishment to the Abstract Expressionists. She focused on the flatness of the picture plane long before it was a concern for Post-Painterly Abstractionists. She was interested in the transcendent powers of abstract fields of color long before the Color Field artists explored similar interests. And decades before Post-Modernist relativism insinuated itself into fine art, O’Keeffe intuitively grasped the idea that all styles, all approaches, all techniques and all variations within aesthetics are equal in their potential value, and ultimately secondary to the primacy of honest self-expression.

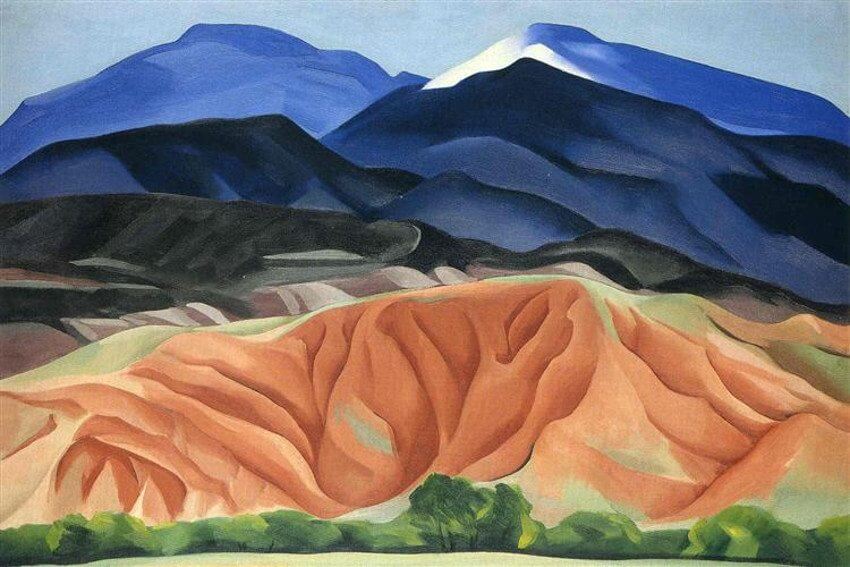

Georgia O'Keeffe - Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico, Out Back Of Mary S II, © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe - Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico, Out Back Of Mary S II, © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Embrace the Formalities

Maybe what has been misunderstood about the art of Georgia O’Keeffe is the same thing so often misunderstood about all art: the idea that art is supposed to possess definable attributes, or be useful or meaningful in some way to the public. We are taught to critique artworks based on whether we like them or not; to skip past the description phase, which requires looking and feeling, rushing instead to the interpretation and judgment phases. We only look at an O’Keeffe painting long enough to get an impression of something we recognize, like what appears to be a flower or a landscape, and thus proclaim O’Keeffe to be a painter of flowers and landscapes. We notice how certain flower parts resemble certain human parts and thus proclaim O’Keeffe to be a secret painter of figurative innuendo. O’Keeffe fluctuates between abstraction and figuration and thus we proclaim her to be responsive to market forces or public expectations. Based on our personal opinions about such things we say, “I love it!” or, “I hate it!”

But that method of critique is immature. To understand Georgia O’Keeffe art, or any art, more deeply, we should linger in the description phase, interacting with the surface, the colors, the hues, the lines, the shapes, and the relationships between those elements as long as possible. Let the formal aesthetic elements of the work sing. Feel the rhythm of the composition. Yes, O’Keeffe did famously once say, “I feel there is something unexplored about woman that only a woman can explore.” But instead of trying to force yourself to see an image of femininity in her paintings, open yourself up to how femininity might feel. What made Georgia O’Keeffe a pioneer of American abstraction was not that she painted images that look like America. What made her a painter of femininity was not that she painted images that look like parts of the female body. What made her a pioneer of American abstraction and a painter of femininity was that she painted the attitudes, impressions and emotions that comprised what America and femininity felt like, to her.

Georgia O'Keeffe - Series I, No 3, 1918 (Left) and Georgia O'Keeffe - Series 1, No 8, 1918 (Right), © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe - Series I, No 3, 1918 (Left) and Georgia O'Keeffe - Series 1, No 8, 1918 (Right), © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

Featured image: Georgia O'Keeffe - Grey Blue And Black, Pink Circle (detail), 1927, © The Estate of Georgia O'Keeffe

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio