How Abstraction Served Avant-Garde Art

Most politicians today ignore avant-garde art. They see it as a harmless bastion for intellectuals trading in esoteric aesthetic philosophies. But that was not always the case. In the not so distant past, power brokers feared avant-garde art as a force that could wield cultural influence, or even alter national character. And avant-garde art movements linked with abstraction were often perceived as particularly threatening, because of the ambiguity of their purpose and unpredictability of their influence. Today we look back at some of the ways abstraction influenced avant-garde art movements of the past, and the impact of those movements on our culture.

Salon of the Refused

1863, Paris

Avant-garde means advance guard. It is a French military term for soldiers who lead the way into new territory against uncertain foes. Its use to describe art dates back at least to 1863. That is the year an avant-garde art movement called Impressionism upended the cultural power structure of France. Since 1667, an institution called the Académie des Beaux-Arts had defined respectable French art. They held an annual exhibition called the Salon de Paris, which bestowed upon select artists the stature associated with approval by the social elite.

The Impressionists were experimenters. They invented new ways of painting; they painted outside, painted everyday scenes, and focused more on conveying light than subject matter. They sought a new way to paint, but also a new way to see the world. Their work was rejected from the Salon de Paris. But Napoleon decided the public should determine whether there was value in the Impressionist style, so he organized the Salon des Refusés in 1963, exhibiting work rejected by the formal Salon. The show was even more popular than the formal Salon, resulting in the rise of Impressionism, and the decline of the power of the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

Salon des Indépendants

1884, Paris

Despite the success of the Salon de Refusés, the idea still persisted that art exhibitions should be juried; that certain elite people should have the power to establish taste. But in 1884, a group called the Société des Artistes Indépendants, which included Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, the founders of Pointillism, helped destroy that notion by creating the first Salon des Indépendants, an exhibition open to any artist. Their motto was without jury nor reward.

During its 30-year run, the Salon des Indépendants helped establish Neo-Impressionism, Divisionism, the Symbolists, Fauvism, Expressionism, Cubism and Orphism. It gave refuge to abstraction and connected likeminded avant-garde artists. It solidified the reputations of Cézanne, Gauguin, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh and Matisse. And most importantly it established that Modernist art was not under the control of any institution, and that society could be accessed, and therefore influenced, by the avant-garde.

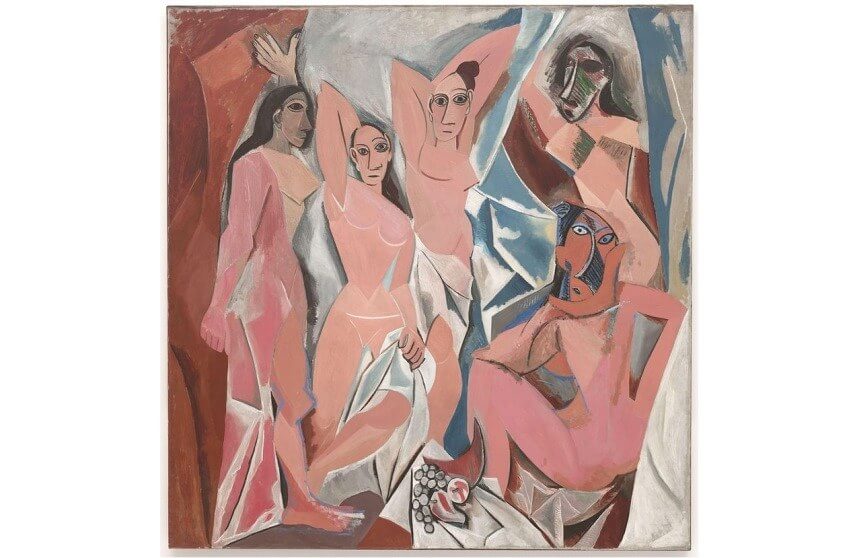

Pablo Picasso - Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907. Oil on canvas. 8' x 7' 8" (243.9 x 233.7 cm). MoMA Collection. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso - Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, 1907. Oil on canvas. 8' x 7' 8" (243.9 x 233.7 cm). MoMA Collection. Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Italian Futurism

1909, Italy

Around the turn of the 20th Century, an overarching evolution occurred in the mindset of industrialized people. The culture transitioned from a trust in the old, ancient ways of running society toward a belief that old and ancient ways were useless. The avant-garde art movement that most clearly expressed this evolution, and solidified it in the minds of the masses, was Italian Futurism.

The Futurist Manifesto, published in 1909, voiced the intention of a new generation of artists to destroy the institutions and ideas of the past to make way for the new. It touted the wonder of machines and speed, and advocated for war to purify society. The abstract Futurist art style was based on showing movement to glorify technology. Their ideas fostered the rhetoric and policies that led to World War I. Several among their ranks died in the war.

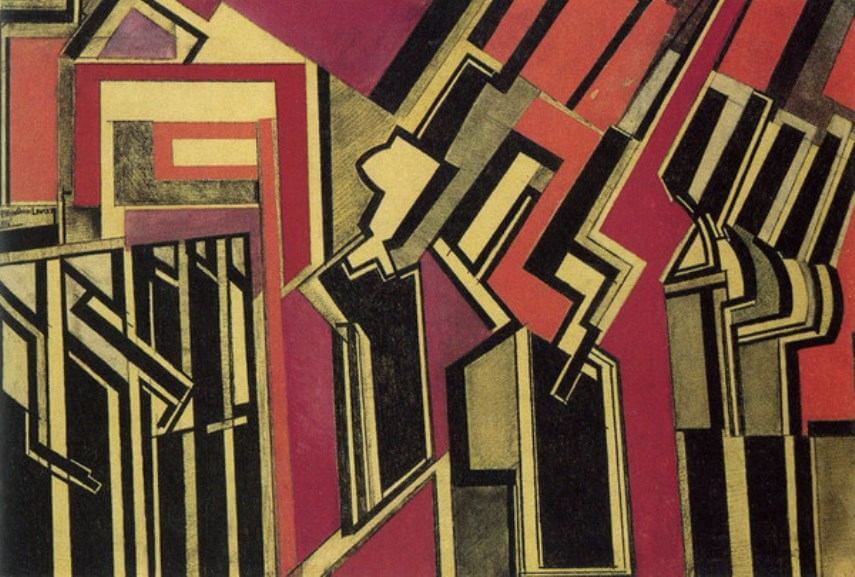

Wyndham Lewis - Vorticist painting. © The Estate of G A Wyndham Lewis

Wyndham Lewis - Vorticist painting. © The Estate of G A Wyndham Lewis

Suprematism and Constructivism

1913, Russia

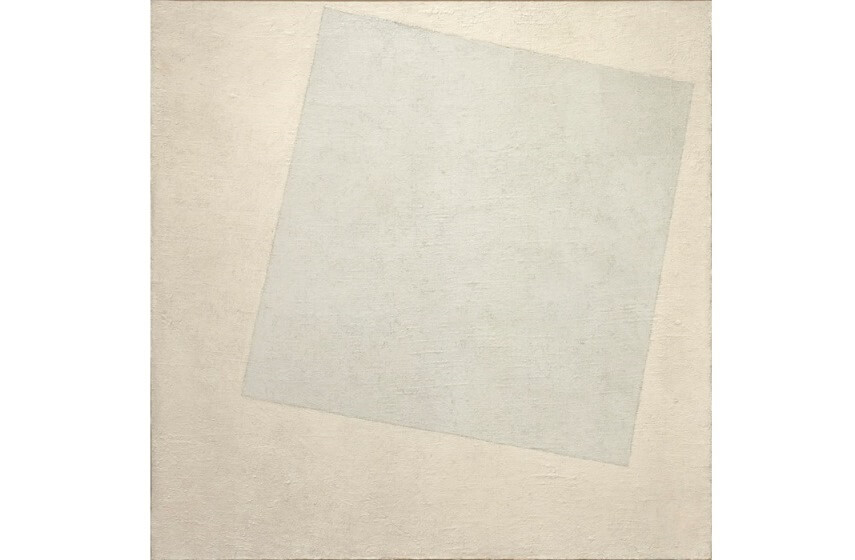

In the aftermath of World War I, two opposing Russian avant-garde movements emerged in response to the vast social challenges facing that country. Kazimir Malevich created an abstract art style called Suprematism, which sought to express universalities in the simplest, purest ways. Malevich wrote in his manifesto, The Non-Objective World, “Art no longer cares to serve the state and religion, it no longer wishes to illustrate the history of manners, it wants to have nothing further to do with the object, as such, and believes that it can exist, in and for itself…”

Simultaneously, Vladimir Tatlin developed Constructivism, an artistic philosophy that art should serve the material world in an objective way. Although Constructivism and Suprematism were directly opposed, both were highly influential. Suprematism established a cultural viewpoint that abstract art, and humanity at large, has a fundamental metaphysical side. Constructivism established a cultural viewpoint that art, and life, is material, and should be approached from a utilitarian perspective. Both viewpoints obviously still thrive today.

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918. Oil on canvas. 31 1/4 x 31 1/4" (79.4 x 79.4 cm). MoMA Collection. 1935 Acquisition confirmed in 1999 by agreement with the Estate of Kazimir Malevich and made possible with funds from the Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest (by exchange)

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918. Oil on canvas. 31 1/4 x 31 1/4" (79.4 x 79.4 cm). MoMA Collection. 1935 Acquisition confirmed in 1999 by agreement with the Estate of Kazimir Malevich and made possible with funds from the Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest (by exchange)

Dada

1915, New York

1916, Zürich

While Russian artists were debating whether art should be objective or non-objective, various artists in New York and Zürich were fostering a third perspective. They considered art, and life, absurd. Responding to the horrors of World War I, the Dadaists took the nihilistic viewpoint that nothing is sacred. They mocked all institutions, styles, philosophies and trends while simultaneously appropriating their tendencies into their art.

The Dadaists created an intentionally chaotic, incomprehensible aesthetic statement. In one sense it was a response to insanity. In another sense, Dadaism created an even more nihilistic culture by validating and nurturing madness. The artists associated with Dada were adamant that they were not making satire. They were not saying anything. They were destroying the idea that art had meaning.

Jean Arp - Abstract Composition, 1915. Collage.

Jean Arp - Abstract Composition, 1915. Collage.

Degenerate Art

1937, Germany

In Post-War Germany, avant-garde artists worked briefly in concert with the larger culture. In 1919, the Weimar Republic instituted far-reaching reforms, encouraging an open, liberal, modern Germany. The Bauhaus emerged in step with Weimar ideals. For 14 years the artists associated with this avant-garde institution nurtured the cultural perspective that art and society should be linked, combining art, architecture and design.

But in 1933, after an economic collapse, the Weimar Republic lost control to the Nazi Party. Nazis opposed Modernism. They forbade any art that outside of their narrow view of historic German greatness. They labeled abstract art, Modern art and avant-garde art as degenerate. The first Degenerate Art exhibition in 1937 marked the beginning of a formal, official attack on anyone associated with so-called degenerate views.

Total Refusal

1948, Canada

While Nazis were taking control of Germany, the United Kingdom was releasing control of many of its territories. In 1931, the UK passed legislation allowing Canada to determine its own legal and national destiny. Canadians thus engaged in a gradual process of determining their national character. A group of artists took the lead in that cultural conversation. Led by Paul-Émile Borduas and Jean-Paul Riopelle, the group published a manifesto in 1948 called Le Refuse Global (Total Refusal).

The manifesto demanded Canadian artists be free from religious and academic control. It embraced abstraction, experimentation and cultural secularism. The immediate reaction to the manifesto was negative, but over several decades it helped instigate the Quiet Revolution, a larger movement that accomplished liberal reforms throughout Canada. Those reforms define the Canadian national character today, and to some extent owe their genesis to Le Refuse Global.

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition, 1954. Oil on canvas. © Jean-Paul Riopelle

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition, 1954. Oil on canvas. © Jean-Paul Riopelle

Gutai Group

1954, Japan

As Japan rebuilt after World War II, an avant-garde art collective called the Gutai Group embarked on a mission to re-imagine Japanese culture. Gutai artists believed the violence of the past was the result of a culture of assimilation and isolation. They believed individuality, creative freedom, a connection to nature, and a connection to other cultures was integral to fostering peace.

The group formed in 1954 and wrote a manifesto in 1956 spelling out their approach to making art. Their work was intentionally abstract and experimental. It sparked a cultural renaissance in Japan. Through the mail they connected with other artists around the world. Gutai directly influenced the Fluxus Movement and many other conceptual art movements in Europe and North America.

Shiraga Kazuo - BB64, 1962. Oil on canvas. 31 7/8 x 45 5/8 in. (81 x 116 cm). © Shiraga Kazuo

Shiraga Kazuo - BB64, 1962. Oil on canvas. 31 7/8 x 45 5/8 in. (81 x 116 cm). © Shiraga Kazuo

The Alternative Artspace Movement

1970s, Global

Beginning in New York, the Alternative Artspace Movement emerged as a global avant-garde movement in the 1970s. Or, perhaps in another way it was an anti-movement, because rather than defining a particular approach to art it simply provided an artist with an environment and the means with which to offer any aesthetic phenomenon whatsoever to the public.

Artists connected with Alternative Artspaces include Cindy Sherman, Sol LeWitt, Louise Bourgeois, John Cage, Judy Chicago, Sherrie Levine, Laurie Anderson, Brian Eno and the Beastie Boys. As an all-welcoming, all-encompassing avant-garde experiment, the movement was itself a fantastic abstraction: an idea of the art world as a totally open experience resistant to all judgment, evaluation and critique.

Sol LeWitt - Wall Drawing 1. © Sol LeWitt

Sol LeWitt - Wall Drawing 1. © Sol LeWitt

Abstraction, the Avant-Garde and Us

In countless cases avant-garde art movements have influenced the cultures in which they existed. It is no wonder that the misunderstanding of abstraction and fear of avant-garde art has caused some of the most powerful regimes and institutions of the past to be openly antagonistic toward art as a threat to their control.

Looking back at the many avant-garde art movements at the past (and there were many more than those we covered), we can see that abstraction was an integral part of their philosophies. Every avant-garde movement is in essence built upon ideas. And so many of those ideas have involved experimentation, open-endedness, ambiguity and artistic freedom.

Featured image: Giacomo Balla - Line of speed (detail), 1913. Oil on canvas

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio