The Glorious Austerity of Ben Nicholson

Nov 16, 2018

When Ben Nicholson died in 1982 at the age of 88, he left behind a troubled legacy in his homeland of England. On one hand, his abstract reliefs are considered by most British scholars to represent the epitome of British Modernism. On the other hand, Nicholson had a reputation for being somewhat of a ham—an artist who changed styles frequently and strategically in order to stay relevant to the market. One day he would make an abstract relief, but then seeing it fail to sell he would the next day switch back to painting a lovely landscape. Whichever version of Nicholson comes closest to reality continues to be a wildly debated topic in Britain whenever a retrospective of his work pops up. Yet to viewers outside of Britain the question is purely academic. The bottom line internationally is that with his relief paintings Nicholson added something unique to the history of Modernist Abstract art—not an easy accomplishment for anyone. His legacy has nothing to do with whether he was making these works because he thought they would sell, or whether he was only trying to be strategic in order to compete with his contemporaries. The reliefs are simply phenomenal examples of austerity and precision, and as such they deserve to be glorified. It is exactly their austerity and precision, in fact, that causes so many people to describe the reliefs as quintessentially British. They are like concrete representations of the British desire for everything in the messy world to be reduced to something simple, crisp, and straightforward. Yet their over-worked surfaces and obsessive methodology also perhaps reveal something else about British culture—that just beneath the surface of that public quest for the austere hides an undercurrent of anxiety and obsession.

The Quest for Novelty

Nicholson was born in 1894 into a family that was literally overflowing with artistic talent. His father and mother were both painters, and his maternal grandmother was the niece of artists Robert Scott Lauder and James Eckford Lauder. Not only did Nicholson grow up to be an artist but so did his sister, and his brother became an architect. Rather than reveling in his artistic heritage, however, Nicholson sought to distance himself from what was, to his mind, a sickeningly romantic vision. Nicholson was a budding Modernist. He wanted to create aspirational works that showed the most ideal aspects of the modern world. With those aspirations in mind, at age 16 he enrolled in Slade School of Fine Art, the most prestigious British art school, in 1910. But he evidently preferred to spend his time shooting billiards instead of going to class, and ended up dropping out after one semester.

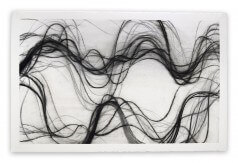

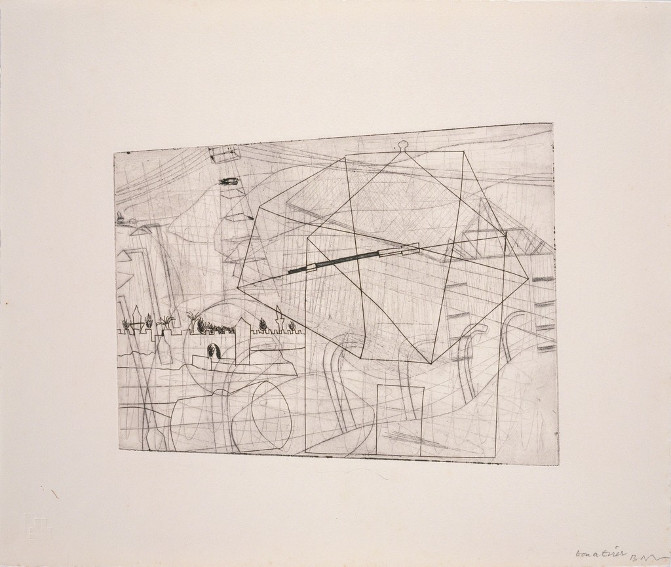

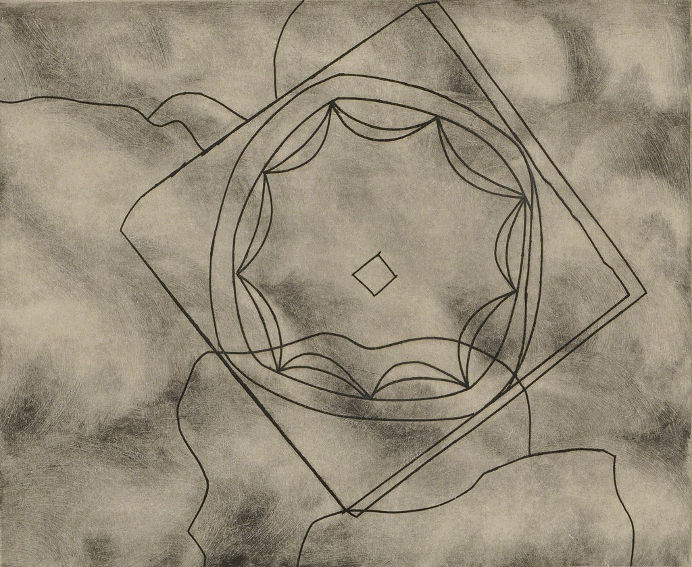

Ben Nicholson - moonshine, 1966. Etching on a used plate (previously I.C.I. shed, 1948). BAT proof; inscribed in pencil 'bon a tirer BN'; inscribed in pencil verso 'artist's proof (moonshine)'; annotations in pencil verso in another hand. 12 3/5 × 15 in; 32 × 38 cm. Photo Courtesy Alan Cristea Gallery, London

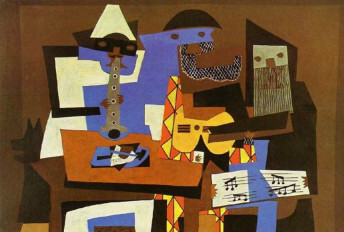

Nicholson later recalled that his best art educational experience came when he traveled to the United States in 1917. While on a visit to California, he happened to encounter the Synthetic Cubist work of Picasso for the first time. The delineation of reality into simplified masses and planes had a profound effect on Nicholson, who compared the rest of the work he made in his life to that standard. Yet it was not until 1924 that he managed to create his own first abstract composition. Titled “1924 (first abstract painting, Chelsea),” it measured 55.4 x 61.2 cm. The oil and pencil work on canvas consists of an arrangement of muted, overlapping squares and rectangles tilted on a slight angle. The surface is painterly but also flat. It seems to reference geometric compositions by artists like Malevich and Mondrian, but its humble material qualities give it a far less academic quality than the works of those artists. But after painting this composition Nicholson returned right back to his landscape paintings and still lifes. It would be ten more years until he would arrive at the abstract relief works that would make him famous.

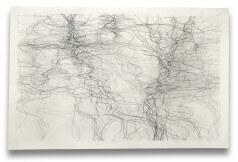

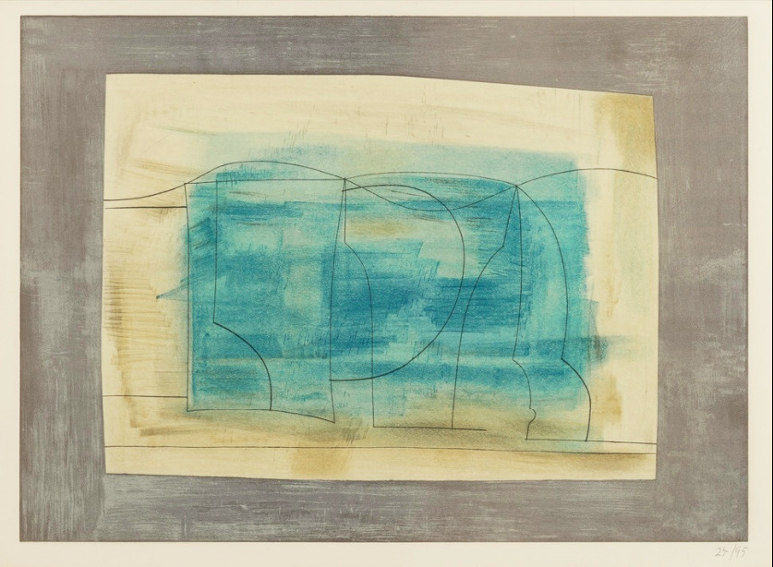

Ben Nicholson - Still Life, 1962. Lithograph on paper. 18 1/2 × 26 in; 47 × 66 cm. Photo Courtesy Frestonian Gallery, London

Sweet Relief

Second to Picasso, the artist who had the most profound influence on Nicholson was Barbara Hepworth. Nicholson and Hepworth began socializing around 1931. Their association started off professional in nature, but soon grew into an affair, causing his first wife to divorce Nicholson. Unlike Nicholson, Hepworth was confident about her quest for abstraction. She believed purely in the value of masses and planes, and knew that an abstract form could be appreciated entirely for its own material and formal qualities. Three years into his relationship with Hepworth, Nicholson made his first carved reliefs. To create these works, he cut simple shapes like circles and squares out of cardboard then glued the sheets of cardboard atop other sheets of cardboard. The works were designed to hang on the wall, their three-dimensional qualities challenging the traditional flatness of painting. He painted their surfaces with muted hues and then obsessively scraped the paint down with razor blades. He likened that process to watching his mother scrub the kitchen table as a child. The worn down aesthetic contradicts the minimal precision of the forms in ways that creates both dissonance and balance.

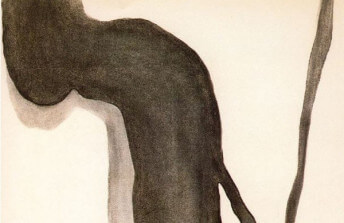

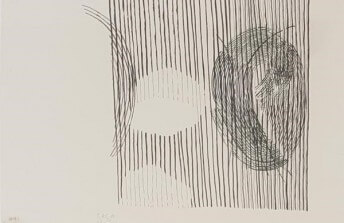

Ben Nicholson - Olympic Fragment, 1966. Etching. 7 9/10 × 9 4/5 in; 20 × 25 cm. Edition of 60. Photo Osborne Samuel, London

Nicholson and Hepworth married in 1938, and divorced in 1951. During their relationship, Nicholson fully matured his pared down, abstract vision. Even after their relationship ended, he continued making his geometric reliefs and pared down abstract paintings. But there were also many periods of time when he retreated back to the comfort of representational work. Maybe it is true that he did so only to make money, since British collectors were not always keen on supporting abstract art back then. Or maybe Nicholson was simply curious about the interrelationship between abstraction and figuration. He perhaps saw his reliefs less as abstraction, per se, as examples of the elimination of ornament. In that sense, maybe he was not trying to abandon representational reality, but was rather trying to expand its definition. If that is the case then like the Constructivists, Nicholson defied any sense of style and instead offered a complex aesthetic vision that encompassed his own hopes for a more novel, more layered, and more honest world.

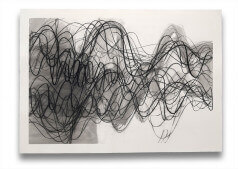

Featured image: Ben Nicholson - long horizontal Patmos, 1967. Etching. Artist's proof; signed and dated 'Nicholson 67'; inscribed verso in pencil. 'BN copy box artist's copy no 6'. 11 7/10 × 17 4/5 in; 29.7 × 45.2 cm. Photo Courtesy Alan Cristea Gallery, London

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio

Featured Artists

Xanda McCagg

1959

(USA)American

Margaret Neill

1956

(USA)American

Jaanika Peerna

1971

(USA)Estonian