What is Cubism - A True Art Revolution?

There are many ways to answer the question, “What is Cubism?” What is Cubism in art? It’s a style of painting in which the subject matter is presented as geometric forms shown from multiple simultaneous vantage points. But there’s more to it than that. Philosophically, it’s a theory of pictorial democracy, where every aesthetic element is valued the same. Intellectually, it’s an admission that life is complex and can only be understood from multiple perspectives. Metaphorically, Cubism is the Internet: it’s a tool for fully exploring a subject, not to get a surface image of what it seems to be, but rather to understand its essence, and to achieve a vision of it that’s complete.

What is Cubism - Art From Every Angle

The coining of the term Cubism is attributed to Louis Vauxcelles, an influential, 20th Century French art critic. Beginning around the year 1907, Vauxcelles wrote a series of critiques about various artists who had begun reducing the pictorial information in their paintings entirely to geometric shapes. He called their shapes “little cubes.” The phrase was intended as derision, but by 1911 Cubism became the common term for what the public was embracing as an exciting abstract style.

The style evolved out of an atmosphere of intense experimentation. Artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were searching for abstract ways to portray life in its full complexity. The Cubist style allowed them to show their subject simultaneously from multiple perspectives. They could assemble an image together from parts seen from different vantage points or show a moving object as it shifted over time from a single perspective.

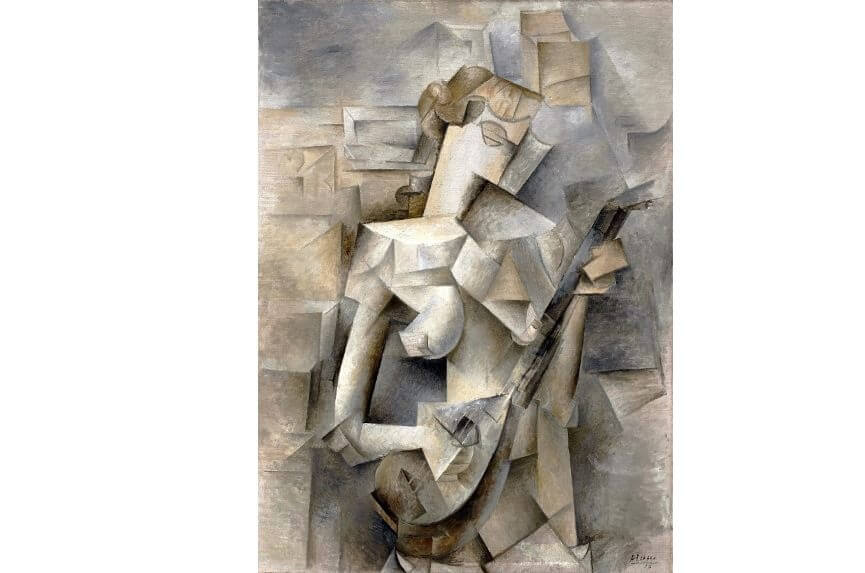

Pablo Picasso - Girl with a Mandolin (Fanny Tellier). Paris, late spring 1910. Oil on canvas. 39 1/2 x 29" (100.3 x 73.6 cm).Museum of Modern Art Collection, New York. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Visual Geometry

The idea of reducing the image to a limited number of geometric shapes, such as triangles, circles and cubes, grew out of the Cubists’ quest for simplification. The point was not to show reality in the usual way, but to explore a more fully realized reality through abstraction. By reducing the visual vocabulary to geometric shapes, the Cubists were exploring the idea that all forms grew out of a small number of basic forms, and that their essential nature could be conveyed through reduction.

The Cubists initially also simplified their use of color, and avoided shading. By limiting their color palette they achieved a greater sense of flatness, which gave equal importance to all perspectives and elements in the picture. By neglecting shading they created a sense of two-dimensionality that democratized space. The combined effect of these simplified techniques drew attention to the individual elements that made up the image: color, line and form.

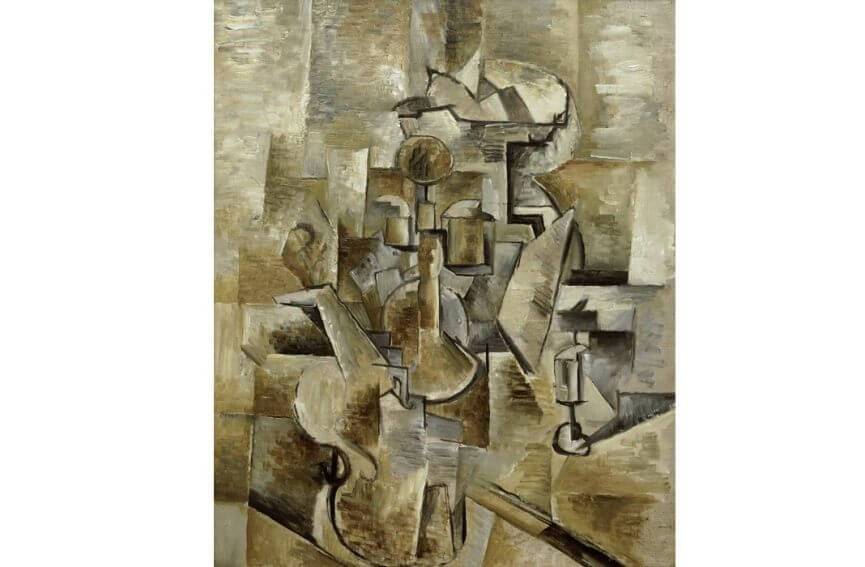

Georges Braque - Violin and Candlestick, 1910. Oil on canvas. 60.96 x 50.17 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) Collection. © 2019 Georges Braque / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Georges Braque - Violin and Candlestick, 1910. Oil on canvas. 60.96 x 50.17 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) Collection. © 2019 Georges Braque / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Analytic vs. Synthetic Cubism

This approach of reducing an image to geometric shapes and portraying it in a flattened way is known as Analytic Cubism. The next step in Cubism’s evolution incorporated other elements to the art besides surface and paint, such as paper or other materials. Academically known as Synthetic Cubism, most people recognize this style as collage. Picasso and Braque were the inventors of collage. By adding bits of newspaper or other detritus to their works, they added new theoretical interpretations to the subject matter.

Synthetic Cubism also involved the use of words painted onto the surface of paintings, which associated high art with the low art of advertising, challenging the differences between the two. Picasso took the idea even further by assembling his collage elements together into three-dimensional objects. These collaged objects weren’t really sculptures, which typically consisted of carved masses surrounded by void. These objects were instead called assemblages, assembled together from pieces of other things. Cubist assemblages incorporated the void, surrounded the void and were also surrounded by the void, breaking new ground as aesthetic phenomena.

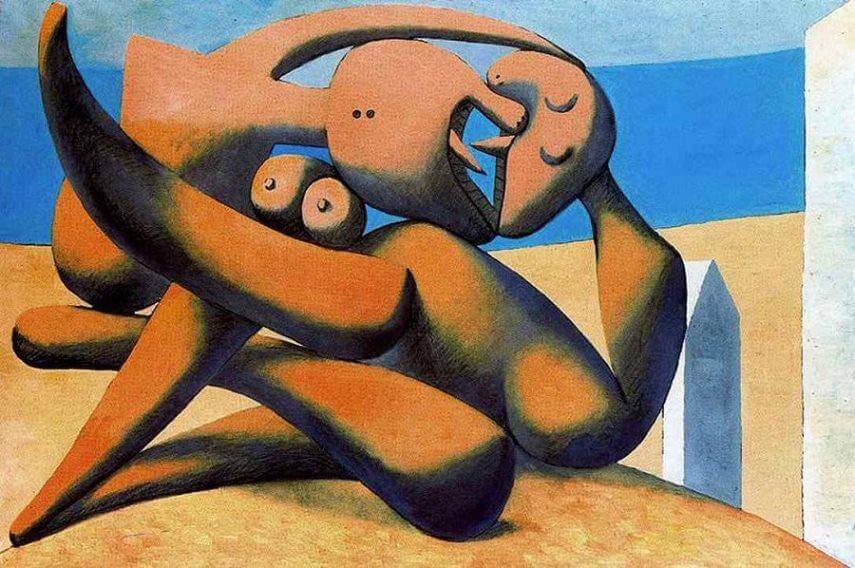

Pablo Picasso - Figures at the Seaside, 1931. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso - Figures at the Seaside, 1931. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Proto-Net

So when we ask, “What is Cubism,” we can say it’s a way of painting pictures made up of little cubes. Or we can say it’s a reductive visual style intended to simplify and democratize the pictorial plane in order to arrive at a more fully realized truth. Or we can say it’s a way of showing multiple perspectives at once in order to experience the entirety of an image, moment or experience.

Or, possibly the best, most complete explanation of what Cubism is, would be: It’s a process. It’s a process of experimentation and exploration. The intent is to arrive at a complete understanding of a subject. Cubism is a manifestation of the same tendency we exhibit every time we take a class, or go to the library, or Google something, or look something up on Wikipedia. It’s an attempt to see all sides. It’s what the Internet was made for. It fulfills an ancient human need to break something into little pieces, look at it from different angles and see it in different lights, so when we put it back together again, though it may not be more precise, our understanding of it will be more complete.

Featured Image: Pablo Picasso - Three Musicians (detail). Fontainebleau, summer 1921. Oil on canvas. 6' 7" x 7' 3 3/4" (200.7 x 222.9 cm). Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund. Museum of Modern Art Collection, New York. © 2019 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio