Drawing Line in Space - The Art of Gego

Gego, otherwise known as Gertrud Goldschmidt, is one of those rare artists who devoted all her energies toward exploring the expressive potential of a single aesthetic element. In her case, the element was line. A trained draftsman, Gego was rooted in fundamentals. She understood the architectonic nature of drawing, and grasped that what holds every construction together is some combination of planes and open spaces. Throughout her career, Gego explored that concept in myriad ways. She created books of lithographs, presenting linear drawings that use only the simplest of marks to create elaborate compositions that seem to contain actual volume. She created sculptures that redefined geometric abstraction using only lines and space, and eventually expanded her oeuvre to a monumental scale, filling entire rooms with impossibly complex, hand woven linear installations that challenge the boundaries of between viewers and art. It is tempting to define Gego as a two or three-dimensional artist, since her works perhaps can be categorized as either drawings or sculptures. But a better description of her work is that it transcended such descriptions, and ultimately created experiences that suggested the existence of entirely new dimensions beyond the straightforward physical realm.

Universalities Within

Gego was born in Hamburg Germany in 1912. At age 20 she moved across the country to attend the University of Stuttgart. She excelled in her classes, but rather quickly, and through no fault of her own, her academic career became difficult. Hitler came to power in 1934. The following year, despite being a natural born citizen, Gego found her German citizenship had been revoked because her family was Jewish. She nonetheless remained in the country and continued with her education for several more years. In 1938, Gego graduated with not one but two degrees: one in architecture and one in engineering. But as soon as she graduated she left Germany forever.

She fled to Venezuela where she began life anew as an architect, taking freelance jobs designing homes and businesses, even operating a furniture design business for several years. She was successful in her work, but gradually she became less interested in the functional, utilitarian aspects of it and more interested in its more introspective elements. Perhaps informed by what she had witnessed in Germany, or by her experiences as a refugee, Gego became dedicated to exploring the universalities she could express through her work. In short, she became an artist. As she later expressed, “Art is firmly rooted in spiritual values. The creator is involved in a continuous process of discovery—not of himself, but of the roots of the universe which he has been able to discover within himself.”

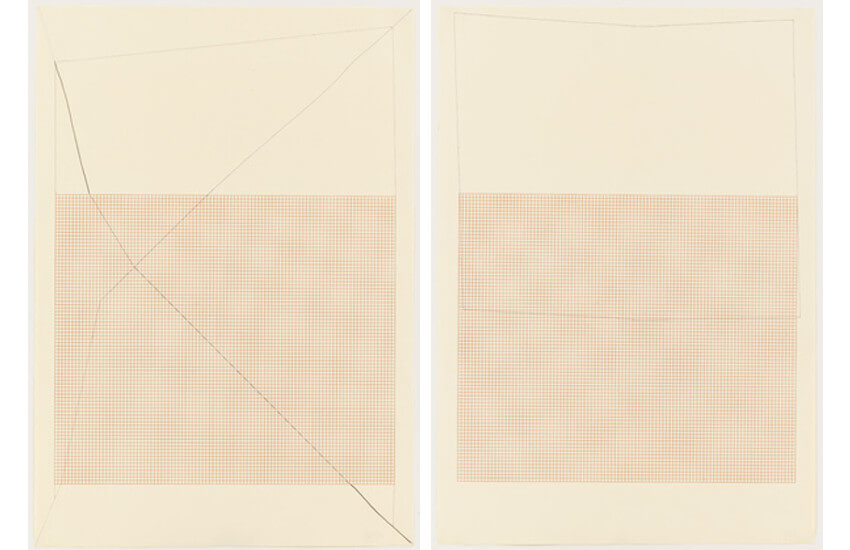

Gego - Untitled (73/14) and Untitled (73/16), © 2019 Fundacion Gego

Gego - Untitled (73/14) and Untitled (73/16), © 2019 Fundacion Gego

Connecting Lines

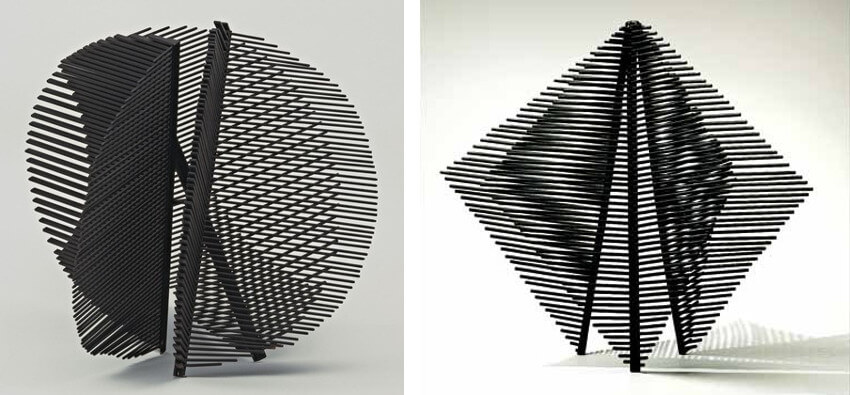

It was the early 1950s when Gego officially abandoned her architecture and design careers to devote herself full time to art. Quickly she gravitated toward abstraction, which was just then coming into fashion in the rapidly modernizing Venezuelan culture. She isolated the fundamental aesthetic element she believed expressed the universalities she had discovered within herself: the element of line. One early sculpture titled Sphere elegantly expresses her fundamental desire to explore the character of lines. The work consists of a conglomeration of horizontal, vertical and diagonal rods that create not so much an actual sphere, but rather a spherical presence. The object contains nothing, and yet it takes on a presence of having volume, especially when one moves around it as the intersecting linear elements collaborate to create the illusion of a rotating orb.

Another object Gego created that same year, called Gegofón, uses the same technique of manufacturing volume with lines. This time she creates the illusion of a cube tilted on its side, in a diamond form. Even more than Sphere, this piece becomes disorienting when one tries to understand the exact nature and construction of the work, especially while moving around the piece, as the intersecting lines make it appear as though more triangular fins are present than actually are. That disorienting kinetic effect is additionally magnified thanks to the patterns created on the ground by shadows.

Gego - Sphere, 1959, Welded brass and steel, painted (left) and Gegofón, 1959, Welded brass and steel, painted (right), © 2019 Fundación Gego

Gego - Sphere, 1959, Welded brass and steel, painted (left) and Gegofón, 1959, Welded brass and steel, painted (right), © 2019 Fundación Gego

Inhabiting Space

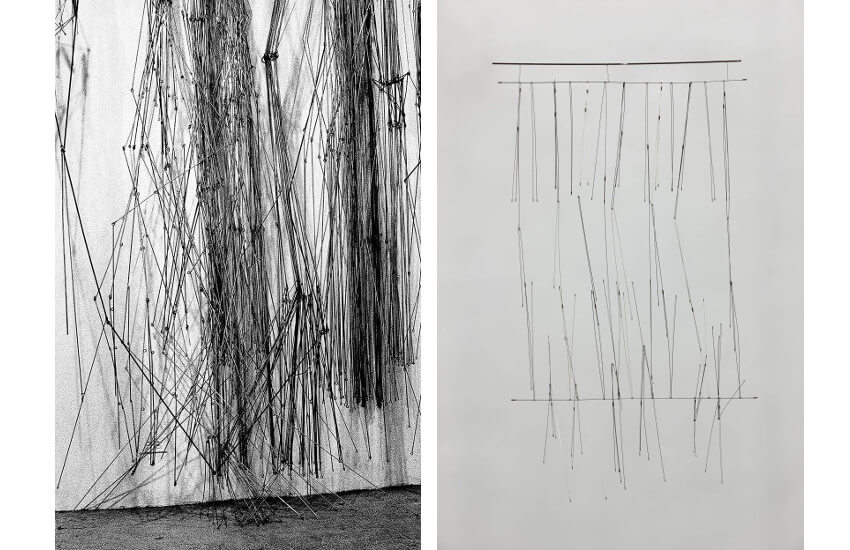

Feeling constrained, however, by the tight geometric qualities of her early sculptures, Gego began exploring new, more personal ways of using lines to create sculptures. She expanded her range of materials, and freed herself from pre-existing geometric forms. In her Chorros series she created tall, thin, almost figurative-looking wire sculptures. The word chorros in Spanish infers something like a strong spray, like a water jet. When they were first exhibited, at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, these sculptures took on the presence of waterfalls.

These more freeform wire sculptures inspired Gego think of the notion that she was drawing, but instead of drawing on a surface she was drawing in space. She thus began a series of works titled Dibujo sin papel, or Drawing Without Paper. Some of these artworks retain an orderly sensibility, and others break free, resembling scribbles in space. All of them, when exhibited in harsh lighting, take on new relationships with other surrounding surfaces and spaces based on the shadows they create.

Gego - Chorros, 1971, Wire sculpture, as seen at Betty Parsons Gallery (left), and Dibujo sin papel 77/20 (Drawing Without Paper), 1977, Iron, stainless steel, enamel and metal small tubes (right), © 2019 Fundación Gego

Gego - Chorros, 1971, Wire sculpture, as seen at Betty Parsons Gallery (left), and Dibujo sin papel 77/20 (Drawing Without Paper), 1977, Iron, stainless steel, enamel and metal small tubes (right), © 2019 Fundación Gego

Stability and Evanescence

The shadows created by her works inspired Gego to think more about the metaphysical aspects of how aesthetic objects occupy space. She realized that the presence of an object is defined by more than physical characteristics alone. Objects have personalities. They affect the empty space around them as much as they affect the space they actually occupy, whether by projecting shadows or by insinuating their presence on the empty space nearby. This idea manifested most dramatically in the monumental installations Gego created, such as Reticulárea (ambientación), pictured below as exhibited at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Caracas, in 1969.

In this installation, the lines themselves present a sense of stability. They are tangible, and occupy space. But the shadows play an equal role in the overall visual experience, and as such are equally tangible from an aesthetic point of view. Also equally important is the empty space between the lines, which allows for the eye to encounter the all of the other elements of the work simultaneously. But the shadows and the empty spaces are in a state of constant precariousness. They represent evanescence, or the sense that something is in a state of simultaneous appearance and disappearance. The work itself occupies precious little space in the room. But the character, or the personality of the work fills every inch of the space.

Gego - Reticulárea (ambientación), 1969, © 2019 Fundación Gego

Gego - Reticulárea (ambientación), 1969, © 2019 Fundación Gego

Transcending Geometry and Kinetics

The most dominant abstract art movements in Venezuela when Gego first entered the art world were Geometric Abstraction and Kinetic Art. It is evident that in the early stages of her artistic exploration Gego was heavily influenced by both positions, but it is hard to categorize her as part of either movement. Her early sculptures definitely played with geometric forms. And kinetics affected her as she repeatedly exploited the idea of movement, albeit not by attaching motors to her works but rather from the standpoint of viewers doing the moving. But neither of those movements offered Gego the full range of growth she needed in her work. She was interested in discovery, and she felt that the only true way to discover anything was to make her work personal.

It is also difficult to categorize Gego as either a two-dimensional or three-dimensional artist. Her works on paper are among the most fascinating and intricate produced by any artists of her generation. They create illusions, capturing the dynamism of Bridget Riley or Jesus Rafael Soto and the delicacy of Agnes Martin. And yet they are so simple: so strictly dedicated to exploring the potentialities of line. Meanwhile her three-dimensional pieces defy categorization. They inhabit space in such a way that the space itself becomes the subject of the work. And yet line is so clearly the subject. Then again, they seem to open themselves up to the possibility that neither line nor space is the true subject. Maybe the subject lies in some other aspect of their presence. Thus it is difficult when looking over her work to lump Gego easily into any category. It is much more accurate, and much more satisfying, to put her into a category all her own.

Gego - two untitled drawings, © 2019 Fundacion Gego

Gego - two untitled drawings, © 2019 Fundacion Gego

Featured image: Gego - Sin Titulo (detail), 1961, Ink on Paper, © 2019 Fundación Gego

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio