Brice Marden and the Calligraphic Treatment of the Line

In addition to traditional paint brushes, spread out on a table in the New York studio of Brice Marden are dozens of sticks. Just ordinary sticks off the branches of trees, except each stick is colored on one tip, a result of having been dipped in ink. Marden draws with them, creating gestural symbols in columns and rows on paper, in compositions evocative of poetry written on a scroll. Drawn intuitively from the imagination of Marden, the symbols are partially inspired by Chinese calligraphy. They are also influenced by objects called gongshí, otherwise known as Chinese scholar stones. Gongshí rocks are found in, or rather chosen from nature. They are prized for their abstract physical properties and are used by scholars for contemplative purposes. Much can be learned from studying their forms, their wrinkles, their perforations, their asymmetrical balance, the glossiness of their surfaces, their textural qualities, their colors, and their resemblance to natural things. As in the paintings Marden makes, the potentialities within the gongshí wait to be discovered, hidden in plain sight within the layers and the lines.

The Plane Image

Brice Marden came to prominence as a painter in the 1960s. He received his MFA from Yale University in 1963 and moved to New York City the same year. He was quickly offered a job as a security guard at the Jewish Museum. There he was able to study the work of his most accomplished contemporaries. Around that period, many of his fellow artists felt a general malaise toward painting. Some derided the age-old rectilinear canvas, and were experimenting with canvases formed into unusual shapes. And many artists were even outright pronouncing painting dead.

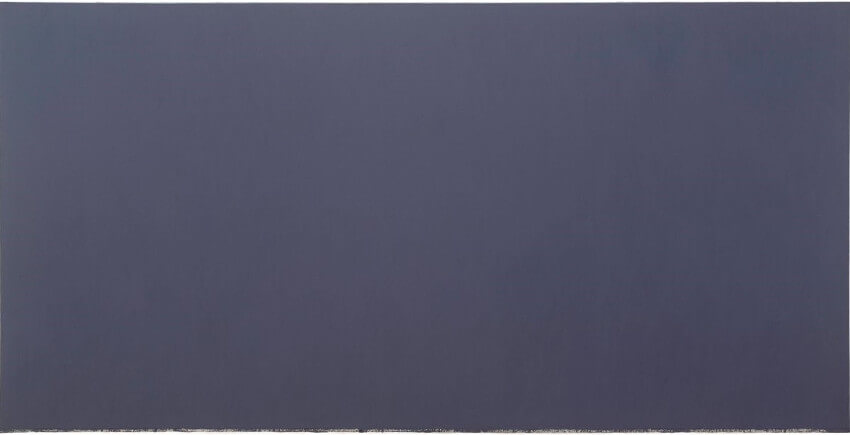

But Marden could not have disagreed more. To his mind there was still plenty for painting to do. Around 1964, he began by focusing his attention on the plane of the painting. Expressed another way, the plane refers to the totality of the surface of a painting. Anything a painter adds to the painting exists within the plane. Much of Modernism was focused on flattening the plane as much as possible, eliminating perspective, push and pull, or anything that would add depth to the picture. To achieve the epitome of that goal, Marden began painting monochromes, which he considered the ultimate manifestation of flatness. He called his version of the monochrome the Plane Image, because, as he said, “the plane was the image.”

Brice Marden - The Dylan Painting, 1966. Oil and beeswax on canvas. 153.35 x 306.07 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, CA. © Brice Marden

Brice Marden - The Dylan Painting, 1966. Oil and beeswax on canvas. 153.35 x 306.07 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, CA. © Brice Marden

In Praise of Rectangles

As for the derision painters in the 1960s felt for the rectilinear canvas, Brice Marden was, and still is, decidedly not in the hater camp. He considers the rectangle the ultimate shape for a painting. In an interview with the National Gallery of Art in 2014, he said, “The rectangle is a great human invention. In the 60s there was a lot of this shaped paintings thing going on. But I really liked the rectangle. And I thought if you could get the exact right color for that form, and you really had it right, if you had absolute correctness of form, god knows what that painting was capable of doing.”

That idea, that a painting can do something, reveals in Marden a deeply held respect for art in general, and in particular for painting. During the years when he was making his monochromes, a larger conversation was going on about what art was and could be. The popular idea was that art could be anything, and that everything is potentially art. Marden disagreed. He defended art as a humanistic endeavor, insisting that an artwork must be made by human hands. Throughout the 1960s and 70s, he made his reputation defending painting through his bold monochromes painted on unapologetic rectangles. This work made him famous, and by 1975 he was considered one of the masters of Minimalism, and received a solo retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York.

Brice Marden - The Seasons, 1974-75. Oil on canvas. 243.8 x 632.5 cm. The Menil Collection, Houston, TX. © Brice Marden

Brice Marden - The Seasons, 1974-75. Oil on canvas. 243.8 x 632.5 cm. The Menil Collection, Houston, TX. © Brice Marden

West Meets East

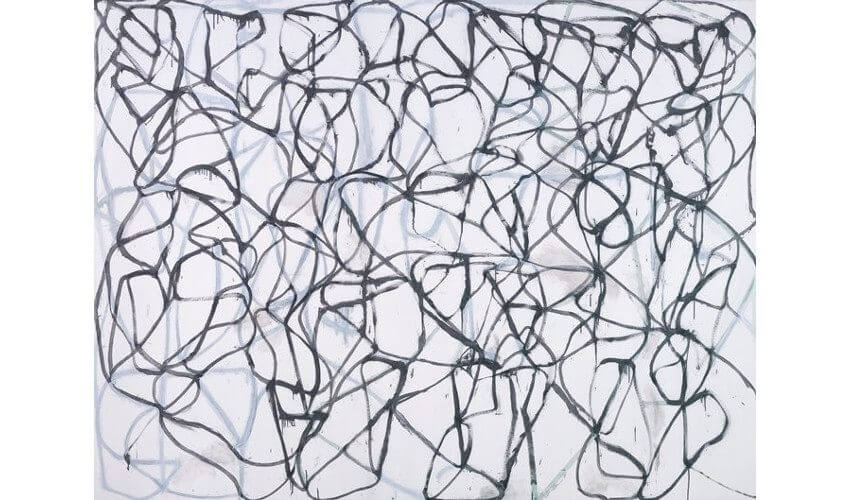

Just as Marden was reaching the height of his fame in the 1970s, he was also beginning to search for new directions in which to take his art. In the early 1980s, he found the inspiration for which he had been looking, when a series of encounters with Eastern culture helped inspire him toward a new relationship with the painted image. In particular, he took notice of Chinese calligraphy, admiring both the gestural lines of the individual symbols and the grid-like quality of the columns and rows of the written couplets.

He began a series of paintings, based on calligraphic aesthetics, called the Cold Mountain paintings. To make them, he painted a layer of intuitive, abstract calligraphic symbols then scraped the paint off and painted another layer of symbols, repeating the process until the composition was resolved. The name Cold Mountain was inspired by the Cold Mountain Poems, a series of hundreds of poems written by a hermetic Chinese monk named Hanshan in the 9th Century. The stark palette and calligraphic look of the paintings speak to the aesthetic of the poem scrolls, while their gestural, layered images invoke the spirit of the poems, which embraced freedom, nature and the quest for harmony.

Brice Marden - Cold Mountain 6 (Bridge), 1989-1991. Oil on linen. 108 × 144 in. 274.3 × 365.8 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, CA. © Brice Marden

Brice Marden - Cold Mountain 6 (Bridge), 1989-1991. Oil on linen. 108 × 144 in. 274.3 × 365.8 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, CA. © Brice Marden

The Scholar Rocks

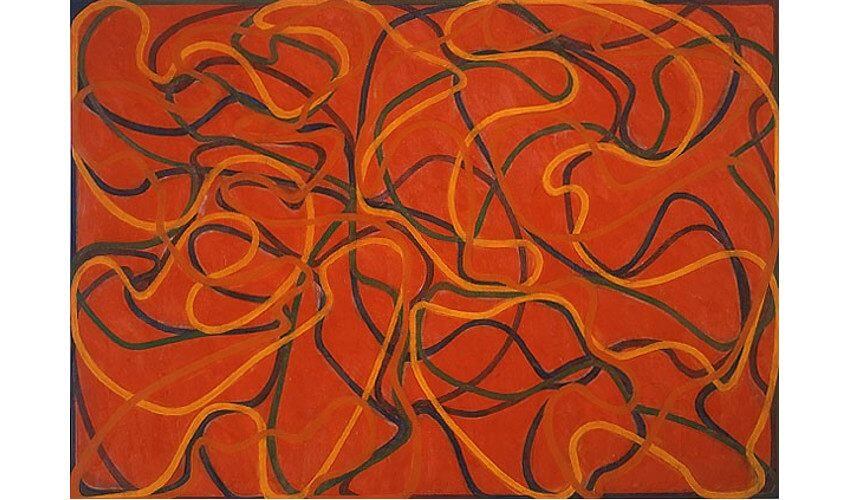

In addition to calligraphy, the other major Eastern influence on Marden was his encounter with gongshí, or Chinese scholar stones. In the stones, it is said, the whole world and all of life is visible. Over recent years, Marden has amassed a collection of scholar rocks in his studio. He explores their intricacies, their patterns, their layers, their color relationships, and the complex harmonies that he observes in them. Those observations have manifested in a series called the Red Rocks paintings.

In the Red Rocks paintings, Marden again works in layers, creating linear forms, scraping them out, painting them over and gradually building up paint until the image resolves itself. The final forms in these paintings seem to relate more directly to the natural forms evident in the stones. But they still contain the gestural energy of his calligraphic marks, lending a constant sense of movement to the compositions.

Brice Marden - Orange Rocks, Red Ground 3, 2000-2002. Oil on linen. 75 x 107 in. © Brice Marden

Brice Marden - Orange Rocks, Red Ground 3, 2000-2002. Oil on linen. 75 x 107 in. © Brice Marden

It Is All In the Painting

Additionally in his Red Rock paintings, Marden extends his use of line out to the farthest edges of the canvas, using line as a way to outline the edge of the frame, enhancing the sense of the rectangular limits of the piece. Speaking about these works recently, he noted that his choice to use line in this way related to questions about the nature of the paintings, and how they were being interpreted. He said, “This picture is not a detail. This picture is itself. Nothing goes on outside of it. That’s what all this framing thing is about.”

That statement, that nothing goes on outside the painting, and that everything essential is contained within it, is vital to the overarching themes of the Eastern traditions that have inspired the calligraphic linear works Marden makes. It is an alternative to the cultural perception that humans somehow exist outside of nature, and can operate independently of it. The reality is that humans are part of nature, not separate from it observing it from the outside. Everything is in nature, including us. Nothing goes on outside of it.

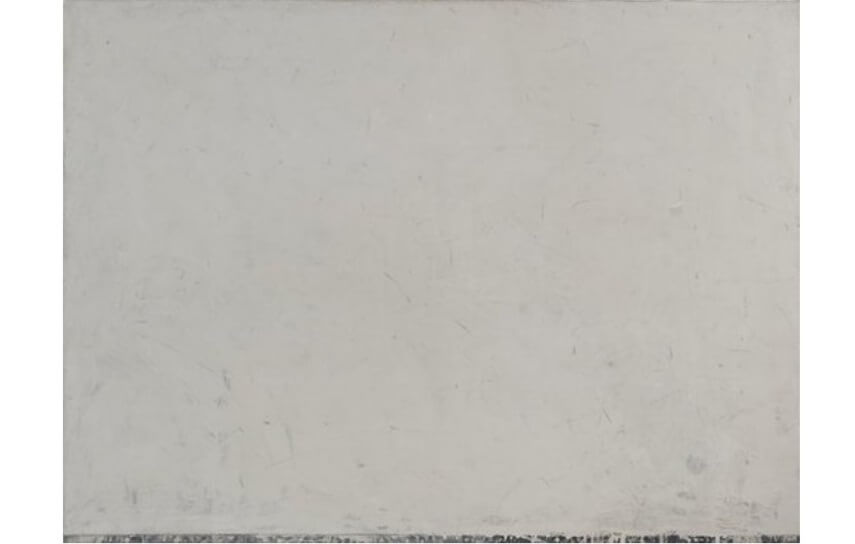

Brice Marden - Return I, 1964-65. Oil on canvas. 50 1/4 x 68 1/4" (127.6 x 173.4 cm). MoMA Collection. Fractional and promised gift of Kathy and Richard S. Fuld, Jr. © 2019 Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Brice Marden - Return I, 1964-65. Oil on canvas. 50 1/4 x 68 1/4" (127.6 x 173.4 cm). MoMA Collection. Fractional and promised gift of Kathy and Richard S. Fuld, Jr. © 2019 Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Blurred Lines

When looking over the past six decades of work of Brice Marden, there are consistencies that carry through the entirety of his oeuvre. His palette is consistently muted, and he has consistently embraced rectangles, either directly in his rectangular paneled monochrome works or indirectly in his calligraphic linear compositions. But there have also been profound changes, as he has moved on from seeking total flatness with the Plane Image to embracing a layered sense of depth in his linear work.

To Marden, those changes represent an element of painting that he appreciates. Each painting he views from each stage of his career is a reminder of who he was at that time. To be able to go back and encounter those works offers him a sense that he is rooted in something unchanging, despite the constant change. As he once expressed it, “One of the things about a painting is that it stays that way. And you can go back to it. And every time you go back to it you’re different, but it’s the same. It’s a stabile thing.”

Featured image: Brice Marden - Second Letter, Zen Spring (detail), 2006 – 2009. Oil on linen. © Brice Marden

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio