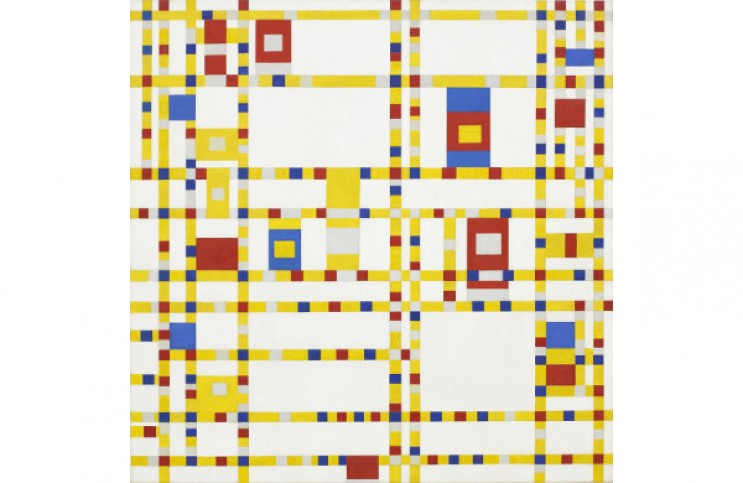

The Rhythm of Piet Mondrian's Broadway Boogie Woogie

Aug 27, 2018

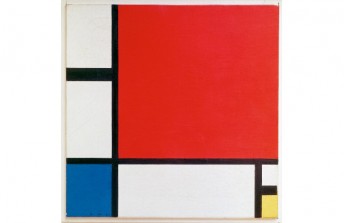

“Broadway Boogie Woogie” (1943) was one of the final paintings Piet Mondrian created before he died. Austere in some ways, chaotic in others, the painting is simultaneously an image of movement and a picture of energy brought to rest. Mondrian considered it a masterpiece—a perfect expression of his intellectual theories. For decades, he had attempted to create a universal visual language capable of abstractly communicating the spirit of the Modern Age. He had methodically pared the formal elements of art down to color, shape, and line, and then pared those elements down further to primary colors, rectangles and squares, and horizontal and vertical lines. His work was both creative and destructive—its aim was to destroy the reliance painters put on figurative subjects by creating a style based on a deeper truth. Said Mondrian, “I wish to approach truth as closely as is possible, and therefore I abstract everything until I arrive at the fundamental quality of objects.” With “Broadway Boogie Woogie” he achieved that goal. He painted a picture of the essence of something real—the lights, energy, and architecture of Broadway—while also distilling that subject into a completely abstract manifestation of a feeling. To him, it was a triumph. And to many of his contemporaries, it was the beginning point for the development of a multitude of other conceptual and theoretical advancements, many of which continue to exert a tremendous influence on abstract art today.

Starting at the Beginning

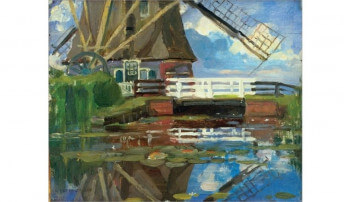

The first mistake people make when they are introduced to the mature style for which Piet Mondrian is known is thinking that Mondrian must not have been able to draw from life. But that could not be farther from the truth. Born in 1872, Mondrian was tutored as a child by his father, an amateur painter, and his uncle, a professional one. He entered art school at the age of 20, and was so adept at drawing from models and copying the Old Masters that he was able to make a living copying museum paintings and making scientific drawings after school. Despite his talent for mimicry, however, Post-Impressionist movements held more promise for him, since they held the promise of creating something new for the future. He learned everything he could about early Modernist movements like Divisionism, Cubism, and Futurism, and throughout his 30s he transitioned quickly through the lessons of every emerging style to which he was exposed.

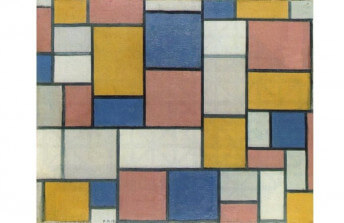

Mondrian took studious notes. He not only practiced the visual techniques of the Post-Impressionists but also deeply analyzed the thinking that underlined their theories. Raised in a Calvinist household, he had been exposed to the notion of spirituality as a child. Through his art studies, he came to reject the exclusivity of organized religion, and instead came to believe that universal spirituality could be attained through the Plastic Arts. The visual theories Mondrian developed may seem simplistic, but they represent what Mondrian perceived as profound truths. The horizontal and vertical lines depict the opposing-collaborating forces of nature—positive and negative, hard and soft, energy and rest. The squares and rectangles represent science and mathematics, structures which Mondrian believed concretely express the mystery of existence based in part on the ideas of Dutch mathematician Mathieu Hubertus Josephus Schoenmaekers. The limited color palette is what Mondrian considered the smallest number of colors needed to convey the importance of relationships. As he said, “Everything is expressed through relationships. Colour can exist only through other colours.”

The Boogie Woogie of Broadway

The original name for the style Mondrian developed was De Stijl. But over time, he became so dedicated to his theory of distillation that he alienated the other members of De Stijl, and started a new style called Neo-Plasticism. The only real differences between the two are that Neo-Plasticism has fewer colors and no diagonal lines. That may seem petty, but to Mondrian purity was the key to universality. And yet despite his strict adherence to these self-imposed limitations, Mondrian found ways to continually make his paintings more interesting. One of the most inspiring times in his life came in 1940, when he was 68 years old, when he moved to New York. To Mondrian, New York epitomized the modern city. He was moved by the energy of jazz music and the seemingly endless pulse of life that moved through the streets. He also admired the fact that unlike other cities in which he had lived, like Paris and London, New York was laid out on a grid that eerily resembled that of his own paintings.

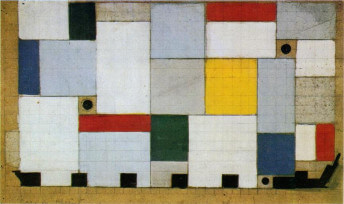

In 1942, Mondrian finished a painting titled “New York City,” in which the familiar black lines of his past compositions were replaced with red, yellow, and blue lines. This seemingly subtle change imbued the work with a thrilling new energy. “Broadway Boogie Woogie” took that idea even farther, inserting squares and rectangles within the lines, and filling squares and rectangles with smaller squares and rectangles. The essential elements of Neo-Plasticism are retained, but also expanded upon. One year after finishing “Broadway Boogie Woogie,” Mondrian died. When he passed he was in the midst of working on another masterpiece, this one titled “Victory Boogie Woogie” in honor of the end of World War II. As with some of his other paintings, this last canvas is tilted 90 degrees. Unfinished at the time of his death, it still contains bits of tape, and the colors are also not pure, nor are the edges of the lines and shapes precise. The surface is quite painterly. Its imprecision offers a rare glimpse into the humanity of Mondrian. It also makes “Broadway Boogie Woogie” the last important work the master completed in his lifetime, and the fullest manifestation of his oft-stated maxims, that “Who makes things move also creates rest,” and, “That which aesthetically is brought to rest is art.”

Featured image: Piet Mondrian - Broadway Boogie Woogie. 1942-43. Oil on canvas. 50 x 50" (127 x 127 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2019 The Museum of Modern Art

Image used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio