Callum Innes' Painting and Unpainting

Scottish painter Callum Innes is an ideal artist for us to pay attention to during our current, shall we say, apocalyptic time. After all, the word apocalypse, in the original Greek, only means to uncover or reveal. If our contemporary association with the word sparks images of catastrophe in our mind, that itself may just be a revelation about how important it has become that some things not be revealed. I am happy to call Innes an apocalyptic painter precisely because his work, in my opinion, is all about revelation. It is an idea embedded in his reputation as an “unpainter.” He earned the moniker unpainter because of his process, which seems at first to be the opposite of other painters. He starts each work by applying a monochromatic layer of paint to his surface then repeatedly goes over the painted area with turpentine. Though technically he is adding continual layers of medium to the picture, the nature of that medium is to remove whatever medium was on the surface before. Each unpainting could be thought of as a relic of a key moment in his process—a frozen moment of aesthetic revelation. It is also, however, tempting to read more into it than that. The monolithic, opaque layer that Innes first constructs in his studio; the way a seemingly incorruptible front completely dissolves into a dribbling mess at the first introduction of a solvent; the realization of the true complexity of structure and layers lurking within what at first seemed simple and unified; the realization that very little is permanent in the end—how could we not see something revelatory about our contemporary moment in the poetry of this process? Yet, as Innes will likely be the first to point out, these apocalyptic unpaintings are not political statements, nor are they allegories. They are simple, material reminders that time will never run out, and nothing is ever finished.

Time Will Never Run Out

Many people describe Callum Innes as a process artist. If something about that phrase seems a bit inadequate, it could be because nothing in the arts comes about except through process. With Innes, what it means is that process is the work. The painting itself, as an object, is only important in so far as it reminds us of the process. The best way to understand is to watch Innes at work in the studio. On the Artimage website, there is a nice video of Innes, made by the French photographer Gautier Deblonde. The video shows nothing but method. It bears witness to process, and to how seriously Innes takes it. We see Innes begin by applying paint to a surface in an attempt to materialize some idea he has about color and form. As he paints a square or rectangle on that main surface, pigment also splatters on the wall and floor—visual and material ripples in space time that you could argue are also part of the work. As the pigment on the main surface accumulates, and the color intensifies, it seems as though the painting could be taken off the wall at that moment and sold as a monochrome. No one would doubt its status as a complete artwork. Yet, just at that moment, Innes starts with the turpentine.

Callum Innes - Exposed Painting Bluish Violet Red Oxide, 2019, Oil on linen, 110 x 107 cm / 43.3 x 42.1 in. Kerlin Gallery

Each new swipe of his turpentine soaked brush causes additional layers of pigment to literally vaporize in thin air. The turpentine also splashes on the floor and the walls, eating away at the paint that splashed on those surfaces, and at the surfaces themselves. As we watch, what began as a painting evolves into an unpainting. Innes, meanwhile, is apparently watching for signs of whatever transformation he was hoping to instigate. Even as he is making this work, he is also projecting backwards and forward in time, remembering every other unpainting he has ever made, recalling what became of it when it left the studio, what people said about it when it was exhibited, and how it looked to him when he himself eventually saw it hanging on a bare wall under gallery lights. As he navigates this process, he is not just making arbitrary aesthetic choices. He is wondering where this work fits in with every work he has ever made, or ever will make. He is fighting the most common demon any artist ever faces: time.

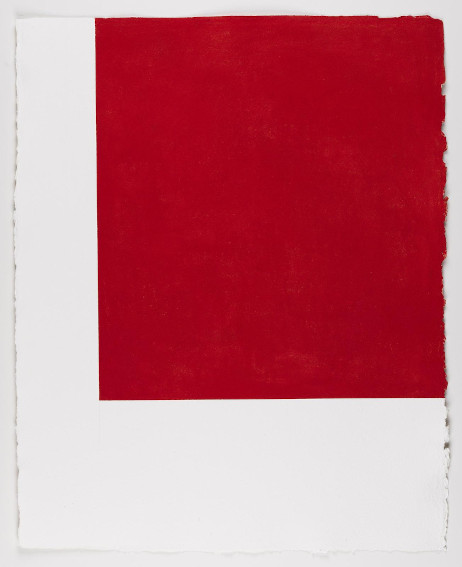

Callum Innes - Untitled, 2017, pastel on Two Rivers paper, 76 x 61 cm unframed / 96 x 81 cm framed. Kerlin Gallery

Nothing is Ever Finished

The relic that comes about in the studio represents only one phase of this process. Long after Innes finishes with it, it still has interactions with viewers to instigate—interactions that will become memories even as light, moisture, heat, dust and mold continue wearing the surface down and building it back up. The most basic assumption any of us make when we see an artwork in a gallery or a museum is that the work is finished. Watching Innes work raises the crucial question of what criteria an artist could possibly use to judge when something is complete? To successfully create something of lasting value, an artwork needs to be more than a snapshot. It needs to mark time, without getting stuck in time. Many artists never really feel their work is complete. They agonize about changes they would still like to make to it, even after the work sells. There is a good reason artists feel this way: because its true, no artwork is ever finished.

Callum Innes - Monologue 1, 2012, oil on canvas, 210 x 205 cm / 82.7 x 80.7 in. Kerlin Gallery

Watching Innes work, we see an artist who has overcome the problem of time by mastering technique; an artist with good humor and fortitude, for whom process is clearly the point—the doing; the intuition; the creative act. He seems to know that as long as the work exists, it will never be finished. He simply stops when what he is doing has taken him, the artist, to the place where he can do something new. Watching the lightheartedness with which he enters into that negotiation, and the ease with which he leaves one unpainting behind to move on to the next, suggests that we should do the same. Instead of analyzing what we see now, we should allow ourselves to be pulled into the layers of time projecting backwards and forward in his work. Unpainting is a reminder that revelation is a process.

Featured image: Callum Innes - Paynes Grey / Chrome Yellow 2011, Watercolour on Canson Heritage 640gsm, 56 x 77 cm / 22 x 30.3 in. Kerlin Gallery

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio