In The Spotlight - Carla Accardi, A Pioneer Italian Abstract Artist

Italian avant-garde artists of the 1960s have always interested me for their seemingly intuitive ability to make art less complicated, while somehow also making it more magical. Carla Accardi, who died in 2014, is a prime example of this phenomena. A major retrospective of her work titled Carla Accardi: Contexts is on view through June 2021 at the Museo del Novecento in Milan, Italy. The exhibition illustrates the paradox I mentioned: that there is nothing we need to explain about her multi-disciplinary oeuvre, yet there is still so much to talk about! Accardi developed a calligraphic vocabulary of abstract shapes and a simplified approach to color that is completely coherent, and which stayed remarkably consistent throughout her 60+ year career. Despite that simplicity and consistency, her work also underwent multiple evolutions. Early in her career, a trip to Paris led her to simplify her color palette: for a while, she only used black and white. Gradually, she added color back into her work, but still limited it to only a few hues. She noticed how the fluorescent paints she used seemed to give off light, however, she was bothered that the canvas absorbed the paint, and thus the color. She wondered how to make the color more pure, and more luminous. Her solution came with the discovery of a type of clear industrial plastic called Sicofoil. Color applied to this material held its brilliance. She made paintings, sculptures, and even environments out of Sicofoil, noting that works made with this material had the effect of revealing what was once hidden. For example, by making a painting out of Sicofoil, the wooden stretcher bars are revealed, bringing the wood to the forefront: an artistic gesture that demystifies the art by putting nature ahead of it. Later, Accardi returned to painting on canvas, and also adopted other materials along the way, such as ceramic and stone tiles. She remained open to where her work would lead her, and followed it with delight, regardless of critical and academic trends. Her magic was in following her own fascinations. This simple fact made her a revolutionary.

The Shape of Writing

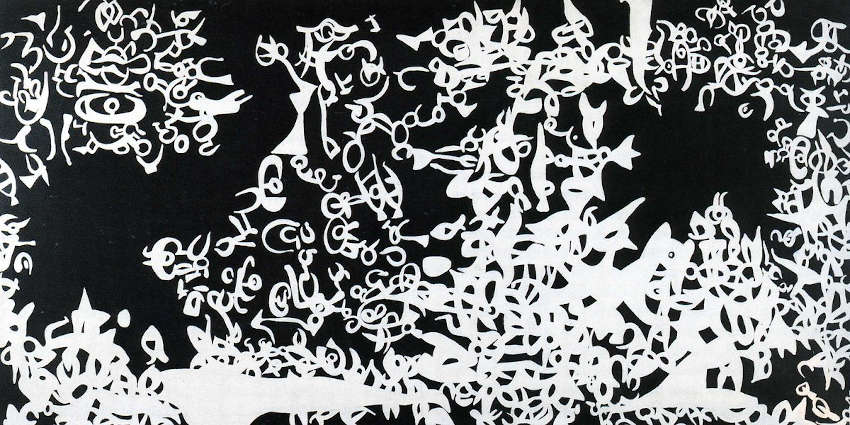

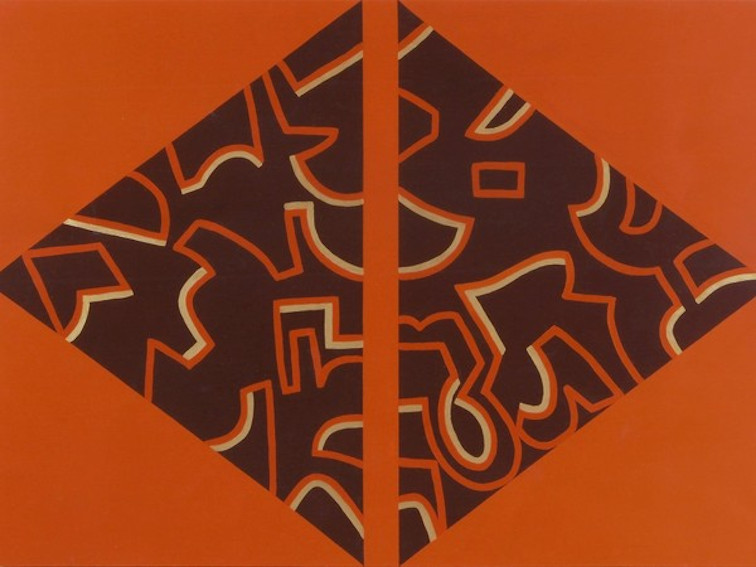

The visual language that Accardi developed early in her career, and then maintained until her death, unlocked a connective tissue between writing, drawing and pattern making. Early black and white abstractions such as “Grande integrazione” (1957) feature her signature calligraphic, linear shapes, in this case gathered in a swarm, forming what could either be read as a unified composition or as a cacophony of unrelated marks. After color later returned to her paintings, we see the calligraphic marks remain in paintings like “Moltiplicazione vedreargento” (1962), where they now occupy a midpoint between color and void. After Accardi discovers Sicofoil, the calligraphic marks continue to provide content in both the paintings and sculptures. Her Rotoli (1965-68)—which are rolled, tube forms made from Sicofoil—are painted with the signature calligraphic lines, as are paintings like “Verde” (1974). Decades later, we still see the writerly shapes appearing in paintings like “Per gli stretti spazi 1, dettaglio” (1988), now enlarged, and “Nelle ombre sui muri” (2005), in which the shapes have turned now into graphic representations of pattern.

Carla Accardi - Grande integrazione, 1957, tempera alla caseina su tela, 264 x 132 cm. Collezione Museo del Novecento

We already know that whatever Accardi was painting on the surface of her works was almost a secondary concern for her. She was more interested in formal considerations, such as color and light. She was fascinated by the philosophical ramifications of showing viewers the backbones of her paintings by using clear plastic, or in the economic considerations of using cheap materials to build habitable sculptures. Some of her most famous works—her Sicofoil tents—were considered groundbreaking as aesthetic environments. The surfaces of the tents are covered in her signature calligraphic marks, and yet this is hardly the point of the works. They are human scaled forms that are meant to be inhabited. The personal, experiential aspects of the tents were what mattered most to Accardi. What then were these marks she was making, if they were never the most important part of the work? This is a simple, and maybe magical question. It seems to also ask: what is all writing, all mark making, and all pattern, except a lens through which to experience the senses?

The Feminine Revolt

Accardi was always at the forefront of the Italian avant-garde. She was a founding member of Forma 1, which re-energized Italian art after World War II, as well as the Continuità group, a re-formation of Forma 1 in the early 1960s. Notably, however, Accardi was the only woman in Forma 1. This was not an accident. In Italy back then, as in most places back then, systematic cultural forces kept members of certain groups from being successful in the art field, or often from even participating in the arts. Accardi is the most revolutionary of the revolutionaries in Forma 1 and the Continuità group, because she did what the the rest did, but she did it fighting up hill as a woman.

Carla Accardi - Nelle ombre sui muri, 2005, vinilico su tela, 160 x 220 cm. Galleria Santo Ficara SRL – Firenze. © Carla Accardi, by SIAE 2020

In 1970, Accardi co-founded the group Rivolta Femminile (Feminine Revolt) with journalist Elvira Banotti and art critic Carla Lonzi. The group authored the Manifesto of Female Revolt, and published their writings through their own publishing house, Scritti di Rivolta Femminile. Feminine Revolt is considered the most influential Feminist art collective in Italy. They advocated for institutional changes when it comes to things like work, marriage, and equality, but that was not all they talked about. They went much deeper, encouraging every woman to look inside themselves for their certainty, not to keep suffering the influence of men or any other outside force. Even after her death, Accardi remains an ideal advocate for “inner certainty.” She forged her own path and created a body of work that, despite its simplicity and consistency, contains ample mysteries and magic.

Featured image: Carla Accardi - Per gli stretti spazi 1, dettaglio, 1988, vinilico su tela, 160 x 220 cm, foto Luca Borrelli Archivio Accardi Sanfilippo, Roma. © Accardi Carla, by SIAE 2019

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio