Legendary Kinetic and Op Artist Carlos Cruz-Diez Dies at 95

Carlos Cruz-Diez (b. 1923), an artist of the people, has died. An obituary posted on his official website reads, “It is with deep sadness that we announce the death of our beloved father, grandfather and great-grandfather, Carlos Eduardo Cruz-Diez, on Saturday 27th July, 2019 in the city of Paris, France. Your love, your joy, your teachings and your colors, will remain forever in our hearts.” IdeelArt was fortunate to have visited the atelier of this captivating artist three different times over the years with various artists—most recently just this last week, on Friday 26 July, the day before his death. It comes as a great shock to us, and a great sadness, that he is now gone. Cruz-Diez was the last surviving member of what Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, Curator of the 33rd São Paulo Bienal (2018), once named the “Holy Trinity” of Venezuelan art, along with Alejandro Otero (1921 – 1990) and Jesús Rafael Soto (1923 – 2005). Together, these three groundbreaking artists helped overthrow the longstanding cultural assumption that art was only meant for the elite. They created art that was meant to be displayed in public for everyone to see, and that was meant to be held, touched, and experienced in person. Cruz-Diez ultimately created more than 100 public art interventions. Some, like “Crosswalks of Additive Color,” (designed c.1960, installed 2011) in front of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, fit seamlessly into the public sphere, using small bursts of unexpected color to remind passersby of the constantly changing nature of daily reality. Others, such as the monumental installation “A Floating Being” (2016), installed at the Palais d’Iéna in Paris, completely transformed architectural environments, creating dramatic situations capable of subverting the public understanding of communal space.

A Kinetic Art Pioneer

When Cruz-Diez earned his degree from the School of Fine Arts in Caracas in 1940, the Venezuelan art field was largely cut off from the rest of the Western world. Even news of Impressionism took nearly half a century to reach his home town. Thus, in 1955, after more than a decade of working as an artist and advertising illustrator after school, Cruz-Diez left Venezuela and moved to Barcelona. From there, he travelled frequently to Paris to visit the studios of his compatriots who had already immigrated to that city. After seeing Optical and Kinetic Art for the first time in the exhibition “Le Mouvement” at Galerie Denise René in 1955, Cruz-Diez knew he had found the way forward. He moved back to Caracas in 1957 and founded a visual arts school then moved permanently to Paris in 1960.

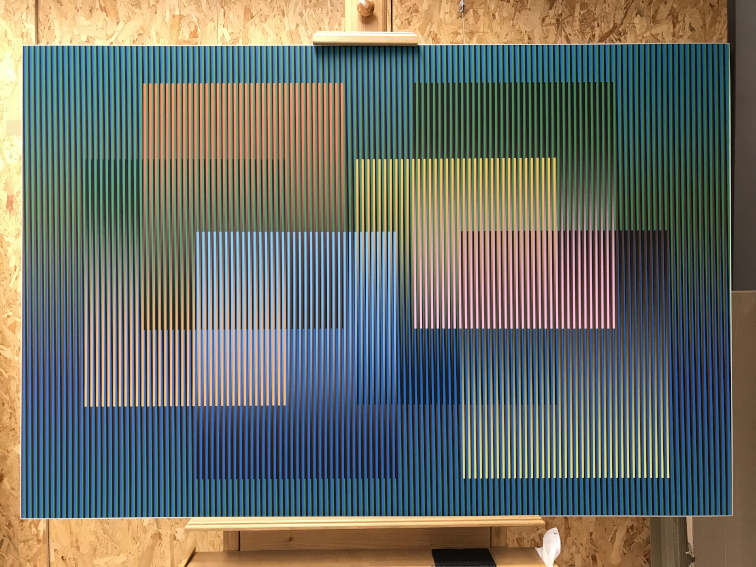

Carlos Cruz-Diez studio. Photo courtesy: IdeelArt.

His earliest Optical works were made by gluing strips of plastic to sheets of cardboard. Their simple construction belied the complexity of perceptual phenomena they instigated. Rather than presenting a single image for a viewer to look at, they required the viewer to move back across their surface to experience the entire work. As the viewer changed position, the work itself changed. Furthermore, as the lighting conditions changed throughout the day, the colors in the work also changed, creating a universe of shifting moods and feelings for viewers who returned to see the work at different times and in different conditions. For Cruz-Diez, the point of this type of work was that it is participatory—rather than simply staring at a painting or a sculpture, the viewer must physically interact with the work to create whatever type of experience they want. As his career evolved, Cruz-Diez grew began using more lasting materials, such as metal, and evolved to create far more elaborate works. Yet, the simple democratic concept at the core of his work remained the same: that the experience is never the same twice, and no two viewers react to the work in quite the same way.

Carlos Cruz-Diez studio. Photo courtesy: IdeelArt.

Saturated in Color

Though the artist was 95 years old, those who were close to Cruz-Diez were nonetheless surprised by his sudden passing, since he remained vibrant and active until the end. One of his most recent installations was in fact also one of his most ambitious—the stunning re-imagining of his 1974 light and color projection “Spatial Chromointerference” inside the 87,000 sq. ft. Buffalo Bayou Park Cistern in Houston, Texas, which just closed on 7 April 2019. The original 1974 version was installed inside of a utilities warehouse in Caracas, the color projected onto the surfaces of the space with slide projectors. Its contemporary manifestation was achieved with 26 digital projectors, which were capable of achieving more pure color, and wrapping the projections around the immensely complicated interior features of the Cistern. Each visitor to the installation became part of the work as the projectors bounced color and light off of their bodies and clothes. The work thus changed with every movement of every body that entered the space—the fulfillment of the notion that art is for everyday people, and fundamental to everyday life.

Carlos Cruz-Diez studio. Photo courtesy: IdeelArt.

Chromosaturations was the name Cruz-Diez gave to such works as “Spatial Chromointerference.” Not all Chromosaturations were so complex; some were as simple as a light projecting color into single room. The purpose is simply to instigate a situation in which a viewer can have their perception challenged. At first, perhaps, viewers may just confront the fact that light and color are inseparable from each other—an idea that Cruz-Diez considered a top priority in his work. But next, they might realize that not only has the room been changed by the color and light, but their own body and clothes have also been changed. The change is both real and unreal; complete, yet also superficial. As the concrete reality of a Chromosaturation changes with every new viewer who passes through it, the meaning of the work also fluctuates according to their inner perceptions. In this subtle way, Cruz-Diez was constantly reminding us that everything is in a constant state of change, and that nothing can be understood from only a single point of view.

Featured image: Carlos Cruz-Diez studio. Photo courtesy: IdeelArt.

By Phillip Barcio