Charlotte Posenenske, a (Forgotten) Minimalist Master

Dec 12, 2018

Dia Art Foundation recently announced the acquisition of 155 sculptural elements by German Minimalist Charlotte Posenenske (1930 – 1985). Posenenske voluntarily left the art world at the height of her career to study sociology and devote her life to helping the poor. To mark her departure, she published a manifesto that ended with this declaration: “Though art’s formal development has progressed at an increasing tempo, its social function has regressed. It is difficult for me to come to terms with the fact that art can contribute nothing to solving urgent social problems.” She gathered up all of her remaining unsold objects, squirreled them away, and never exhibited her work again. She spent the rest of her life searching in earnest for ways to help build a more equitable, just world. Even when she was making art, Posenenske was a fierce advocate of the working class. She tended not to make single objects that could be turned into precious commodities. She created designs for objects that could be mass produced then sold them at cost, earning no profit whatsoever. I reached out to Dia Art Foundation to inquire how much they paid for the 155 pieces they acquired to see if her estate maintains this same practice. A spokesperson for the foundation replied, “Thank you for your interest in Dia’s recent acquisition of works by Charlotte Posenenske. However, we prefer not to disclose details surrounding the commercial and financial aspects of this.” Perhaps such details do not matter anyway. Whether her work is now being commodified or not, and regardless of her own intent, the moment Posenenske left the art world behind with prejudice she gave up her agency to influence how future generations interpret her work, or to dictate what value we choose to assign it.

A More Democratic Art

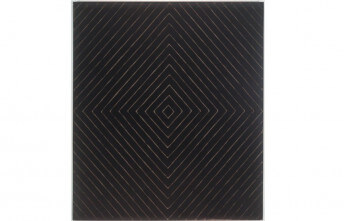

Posenenske was born in Wiesbaden, central western Germany, in 1930, to a Jewish family. When she was nine years old, her father committed suicide fearing arrest by the Nazis. Thanks to the kindness of strangers, Posenenske survived the holocaust hiding out in the city and later on a farm. She began her art career in 1956, the year after the end of the military occupation of West Germany. The forces of industrialization and mass production dominated the economic and social fabric of her culture. Yet in this brave new world, Posenenske saw that the laborers were being exploited same as always—a fact that profoundly affected how she viewed her art. She directed her aesthetic efforts towards universal ideas. Her earliest works were paintings and drawings that explore formal, idealistic Modernist tropes such as line, shape, and color. Gradually, her work grew farther away from anything that would reveal the hand of the artist. She longed to make things that were universal, and which contained no narrative outside of their own objective qualities.

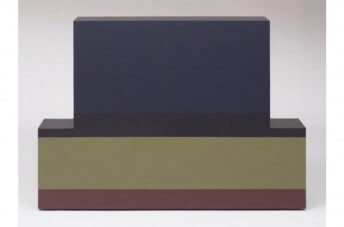

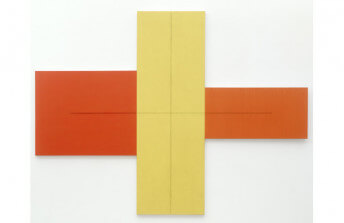

Her ideas connected her to Minimalist artists like Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt, who embraced seriality, industrial manufacturing, and the idea that anyone should be able to reproduce the work of an artist. She moved beyond painting and drawing towards having monochromatic metal reliefs manufactured that could be attached to the wall or placed on the floor and arranged in any manner that suited a space. Next she moved into the realm of objects that could be manipulated by viewers. Her “Revolving Vane” (1967) sculpture is a giant particle board box tall enough for an adult human to walk inside, with eight “doors” that can be opened in any configuration. Viewers walk into the box, open and close the doors then walk away, making the work different for each new viewer, and leaving it in a perpetually unfinished state. Her final works were made of either cardboard or metal, and were designed to imitate heating and cooling ducts. They were mass produced, sold at cost, and Posenenske encouraged every buyer or installer to assemble them into any configuration they desired. This strategy challenged the authenticity and sanctity of the art object, and inherently declared the users and manufacturers of human culture to be equal in importance to its designers.

Charlotte Posenenske - Vierkantrohre Serie D, 1967-2018. 9 elements in hot-dip galvanised sheet steel, screws. 78 7/10 × 19 7/10 × 77 1/5 in; 200 × 50 × 196 cm. This work is a reproduction. Galerie Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin

Radical Acts of Conscience

In her essay “Public Options,” perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of the philosophy of this artist to date, art historian Christine Mehring points out the intrinsic poetry of the works with which Posenenske ended her career. Mehring writes, “interconnectedness and circulation is implied by her “Ducts,” such an elegant expression of the modern world the artist found herself in. It frames Posenenske as a sort of idealistic, or at least optimistic opposite of the artist Peter Halley, whose paintings of “Prisons” and “Cells” offer a dystopian, claustrophobic image of contemporary interconnectedness and circulation. Yet it is obvious from the manifesto Posenenske penned at the end of her art career that she never truly saw herself as an artist. She was never compelled to make art. She considered it a means to an end. She was an activist—a humanitarian who longed to initiate equity and peace. When art stopped serving her activist needs, she turned her attention to other things.

By acquiring so many pieces by Posenenske, the Dia Art Foundation is inviting a larger conversation about the meaning and value or the work this artist did. We are free to look at the work purely for its aesthetic qualities. After all, Posenenske ultimately rejected its social and philosophical value—we are certainly under no obligation to consider it on those levels (not that viewers of any artwork ever are anyway). Yet seen from a purely formal perspective, the work Posenenske did is hardly impressive to my mind or to my heart. As objects devoid of deeper meaning, her paintings, reliefs, and especially her “duct” sculptures deserve little more than a brief historical footnote—eventually someone else would have made sculpture that looked like air ducts if she never had. But they swell with importance when contemplated along with the bigger questions Posenenske asked. Filtered through the altruistic perspective that art can be used as a tool for social change, the entire oeuvre of this artist and the acquisition of so many of her works by Dia Art Foundation can both be seen as radical acts of social conscience.

Featured image: Charlotte Posenenske - Series D Vierkantrohre, 1967-2018. 6 elements, hot-dip galvanised steel sheet. Galerie Mehdi Chouakri, Berlin

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio