The Complex Minimalism of Robert Mangold

The magic in art is personal. It begins when someone is transformed through an aesthetic experience, and becomes inspired in turn to transform the world. Many viewers perceive the art of Robert Mangold as magical because of the subtle, contemplative ways it has helped transform the way they see shapes and patterns in the world. His work is minimal, expressing the simplicity of forms in space. Yet it is also extravagant in its aesthetic depth. It speaks to the personal aesthetic experience Mangold had after first moving to New York City. The urban landscape had a transformative effect on the way he perceived of his surroundings. He came to see the buildings and plazas and roads and bridges not only as functional structures, but also as ethereal shapes. He saw the empty spaces in between the buildings also as forms, equal in value to their material counterparts. He described it as seeing, “Pieces of architecture that are both solid and atmospheric. A similar form in one way could be a gap between a building and in another way could be a building.” Something in the aesthetic of the city helped his eyes simplify the anarchic visual puzzle, transforming it into a sensible world of living geometric forms, like magic.

Paring Down

Mangold moved to New York in 1961, when he was 24 years old. He had just finished his BFA at Yale and married fellow artist Sylvia Plimack. He took a job as a security guard at MoMA, which was common for creatives at that time. The museum paid well and had reasonable hours, and it afforded the opportunity for artists to be in the presence of great works of contemporary art. Like many others in his generation, Mangold was actively looking for ideas. He was seeking a way to start something new.

The previous generation of American artists had been dominated by Abstract Expressionism and Conceptual Art. The idea of paring things down was on the minds of a lot of artists, and it seemed right to Mangold as well. He translated the aesthetic vision he had of the city into minimal, shaped, monochromatic forms. His efforts were rewarded in 1965, when his works were included in the first major exhibition of Minimalist art at the Jewish Museum in New York. Ever since, Mangold has continued exploring the solid yet atmospheric architecture of his visual environment. His iconic oeuvre has helped define Minimalism. And yet in some ways it has also challenged its most sacred philosophical grounds.

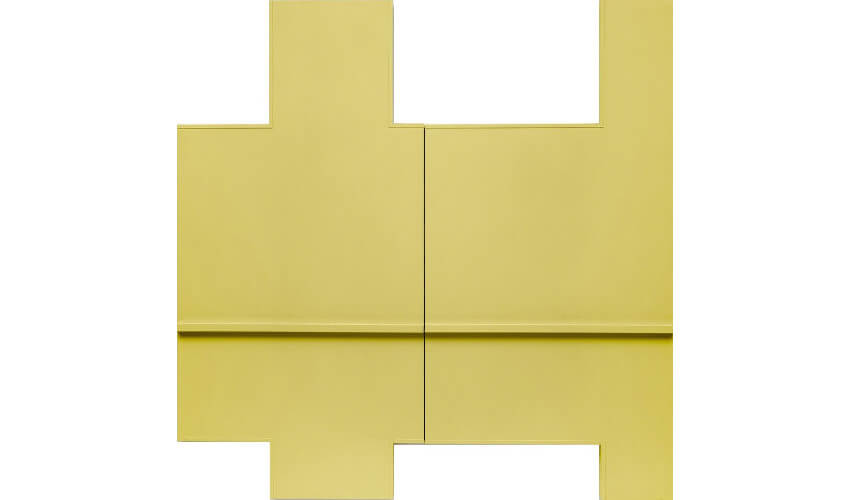

Robert Mangold - Yellow Wall (Section I and II), 1964. Oil and acrylic on plywood and metal. © Robert Mangold

Robert Mangold - Yellow Wall (Section I and II), 1964. Oil and acrylic on plywood and metal. © Robert Mangold

Minimal Direction

Looking back at the roots of Minimalism today, we can easily become bogged down by what seem to be the rules of the movement. We read critical explanations of what early Minimalists did, and read interviews with the artists as they reflect back on what they were thinking back then. Eventually those hindsight reflections combine to define the movement, at least in an academic sense. But we forget that in its primordial phase it was not a movement. It was an attitude, a common cultural perspective shared by likeminded artists drawn toward certain modes of expression. Out of that mindset, trends arose. But at first, at least, there were no rules.

The reason Robert Mangold seems to both define and challenge Minimalism is because of those supposed rules. His work is minimal, meaning it is pared down and simplified. But traditionally, Minimalists are supposed to remove all evidence of their personality from their work. Minimalism rejects ego and emotional complexity. But Mangold makes work that is highly, albeit subtly expressive. It is informed by his personal vision and it communicates in a unique, idiosyncratic voice. Additionally, Minimalism prefers perfect surfaces, vibrant colors and manufactured forms. Mangold makes imperfect, handmade artworks that incorporate what he calls generic colors. His brushstrokes are visible and obviously made by a human, not a machine. But rather than defying the rules, Mangold is saying there are none. Minimalism is mostly about simplifying; showing less expression, not none.

Robert Mangold - Ring Image H, 2009. Acrylic and pencil on canvas. © Robert Mangold

Robert Mangold - Ring Image H, 2009. Acrylic and pencil on canvas. © Robert Mangold

Wherever You Go

Shortly after moving to New York, Mangold and his wife had an opportunity to house sit, or rather farm sit, for a friend in the country. Mangold was of the opinion that the only place for an artist to work was the city. He feared that a lack of culture existed in the rural parts of America, which would make it difficult for an artist to find a sense of community. Also, his artwork was based on the architectural geometry of the urban landscape, so he was concerned that being surrounded by nature would leave him uninspired.

But after arriving in the countryside he soon noticed many of the same patters and forms played out in the natural landscape that he had seen in the city. They just needed simplifying. One of the most immediate things he noticed about his new rural surroundings was the presence of curves. Rather than working with the biomorphic, unwieldy curves of nature, he worked with a compass to adapt them to a more precise expression of their essence. The resulting work expresses the coming together of something natural and something built, something simple and something complex.

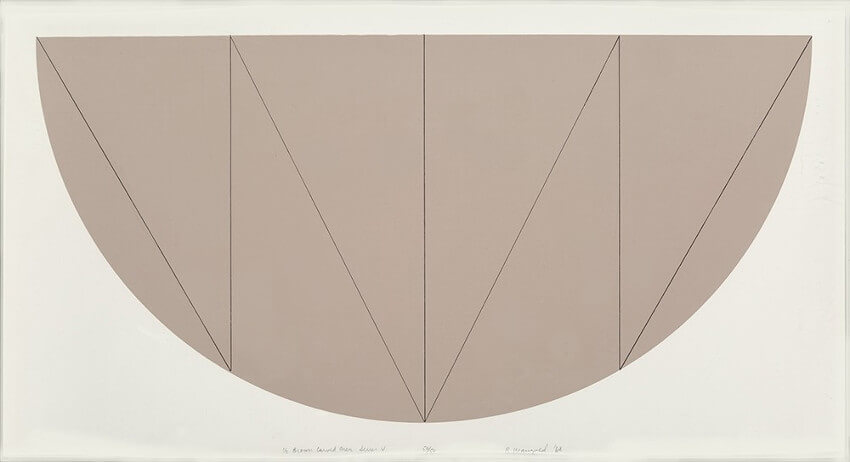

Robert Mangold - 1-2 Brown Curved Area, Series V, 1968. Screenprint. © Robert Mangold

Robert Mangold - 1-2 Brown Curved Area, Series V, 1968. Screenprint. © Robert Mangold

There You Are

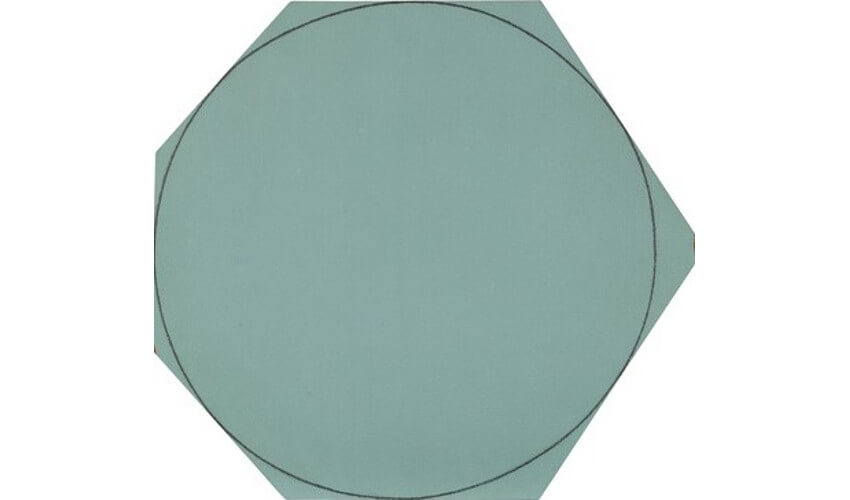

That mixture of simplicity and complexity is something that Mangold has continued to elaborate on throughout his career. Much of the complexity in his work comes from the fact that he never shies away from demonstrating the presence of the artist in his art. In paintings like Distorted Circle Within a Polygon (Green) he addresses the marriage of imperfection and precision that defines the human relationship with nature and art. And in paintings like Irregular Yellow-Orange Area with a Drawn Ellipse he asserts the hand-made aspect of the work upfront, including it in the title, ensuring viewers give consideration to the fact that an individual made the piece.

Robert Mangold - Distorted Circle Within a Polygon (Green), 1973. © Robert Mangold

Robert Mangold - Distorted Circle Within a Polygon (Green), 1973. © Robert Mangold

Through his unique approach to Minimalism, Mangold has achieved an immediately recognizable aesthetic. More importantly, he has also achieved an aesthetic expression of balance. His work occupies a middle ground between the handmade and the mechanical, the geometric and the natural, the perfect and the off-kilter. The formalist concerns he addresses are undeniable, like the power in structure and the inherent quiet strength of a harmonious form. Equally undeniable is the expressive humility of his brushstrokes, the relaxed confidence of his ideas, and the contemplative depth of his compositions.

Robert Mangold - Irregular Yellow-Orange Area with a Drawn Ellipse, 1987. © Robert Mangold

Robert Mangold - Irregular Yellow-Orange Area with a Drawn Ellipse, 1987. © Robert Mangold

The Influence of Robert Mangold

The biggest legacy Mangold has created is the sense of freedom contemporary minimal artists enjoy, to expand beyond the so-called rules of tradition. Swiss artist Daniel Göttin expresses great joy through his Minimalist works. His materials and surfaces show Minimalist roots, while the wit and whimsy of his idiosyncratic creations redefine how the tradition can be interpreted. Similarly, British artist Richard Caldicott combines a Minimalist aesthetic in his interdisciplinary works with a more expressive sense of openness and ambiguity that invites contemplation. And Dutch painter José Heerkens expands the boundaries of Minimalist tradition by embracing raw materiality, texture, and hand painted surfaces. Her paintings use a minimal language of line and form while exploring more temporal concerns such as systems, energy, and balance.

Since the days of his first art job as a museum guard, Robert Mangold has achieved a deservedly prominent stature in the art world. His first solo museum exhibition was at the Guggenheim, and he has appeared four times in the Whitney Biennial, most recently in 2004. His persistent personal confidence is an inspiration for all creatives, and at age 79 he remains an active influence on contemporary Minimalists. It might be inaccurate to say Mangold alone inspired the relaxation of the constraints of the Minimalist tradition. But through his commitment to demonstrating that minimal art can also be complex, he has at least helped free us from the strict boundaries and humorlessness once attributed to Minimalist concerns. And he has also given us magic.

Featured image: Robert Mangold - X Withing X (Red, Yellow, Orange), 1981. Acrylic and black pencil on canvas. © Robert Mangold

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio