Who are the Most Innovative Representatives of Chinese Abstract Art Today?

The phrase “Chinese abstract art” is troubling for me. China is home to the longest, continuous tradition of art making on earth today. That tradition is immense and complex, far more so than the traditions of Western art. The Western understanding of the word abstraction refers mostly to the absence of figuration. But in China, non-figurative art has a completely different history, one as political as it is aesthetic. And the word abstraction means something different to the Chinese than simply the absence of figuration. Nonetheless, I keep thinking that on some deep level, some universal understanding of the meaning of abstraction could emerge if Eastern and Western culture could confer more frequently on the topic. To that end, a recently opened exhibition of Chinese abstract art in Hong Kong has opened some doors for me, and given me a deeper level of understanding. Time Line, Abstract Art From China, on view at 10 Chancery Lane Gallery through 10 October 2018, features the work of four contemporary Chinese abstract artists whose work specifically focuses on the element of line. Curator Tang Zhui points out in his writing for the exhibit, “their ‘abstraction’ is very different from the classical abstract works of Western modernism. They are not intended to present an absolute idea nor pursue the so-called ‘significant form’ approach theorized by art historian Clive Bell, nor do they move toward complete materialism as minimalism. The creation is rooted in the daily manual process of making the works, using their own being to have a constant dialogue with the object over an extended period of time.” This comment suggests that indeed there is something specific about the way Chinese artists use and understand the word abstraction. But it also hints at what is universal about the word, and suggests that my contemporary, Western way of understanding the value of abstract art may not be so different after all.

Linear Depth

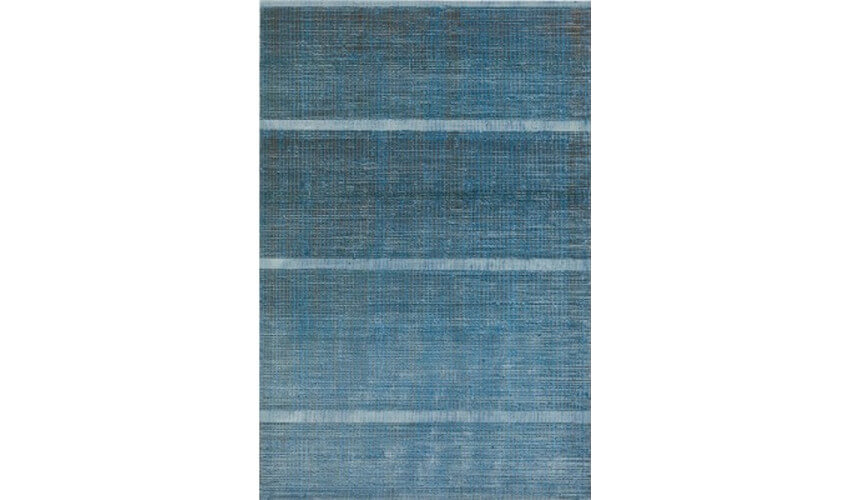

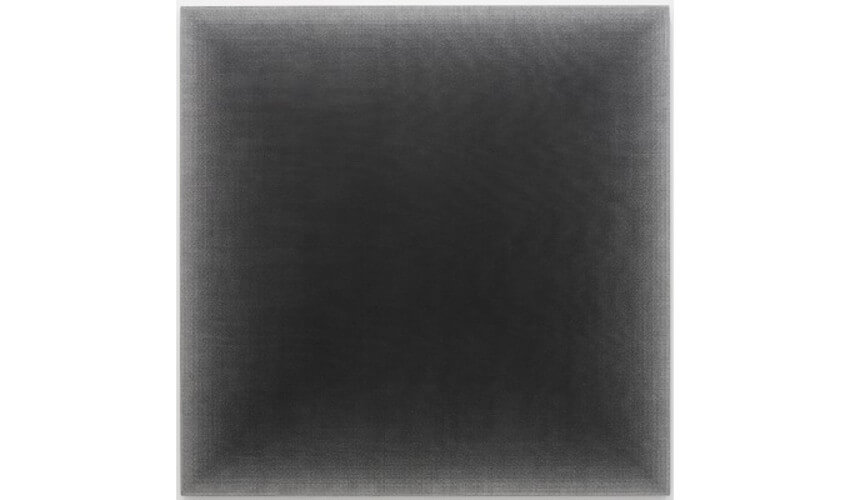

The artists featured in Time Line, Abstract Art From China were all born between 1973 and 1981. Three received formal art educations, and one was self-taught. Their various approaches are highly individual, yet they reveal several commonalities. Liu Wentao trained in Beijing and also in Massachusetts. He creates complex, geometric, trompe l’oeil forms using delicate lines drawn with graphite on canvas. His imagery bridges Western Modernist history with a distinctly Chinese practice rooted in rigor, simplicity and repetition. Chi Qun graduated with a Masters Degree in mural painting from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing. Her paintings have such texture and depth that they almost appear to be made of woven textiles. But what you are actually seeing is as many as eight successive layers of pigment, meticulously applied and then scraped. Part painting and part relief, these works speak to a system of thought and action that is rooted in nature, and is inherently reliant on underlying relationships.

Chi Qun - Four Lines - Grey Blue Brown, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 150 x 100 cm

Chi Qun - Four Lines - Grey Blue Brown, 2017, Oil on Canvas, 150 x 100 cm

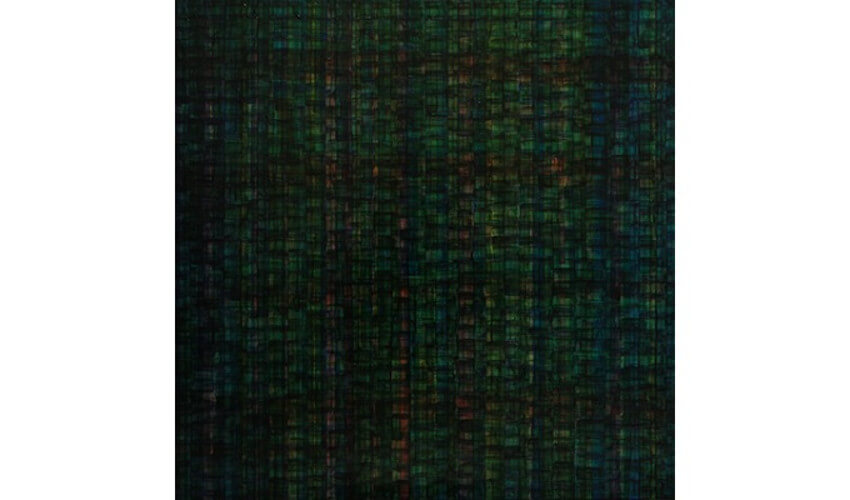

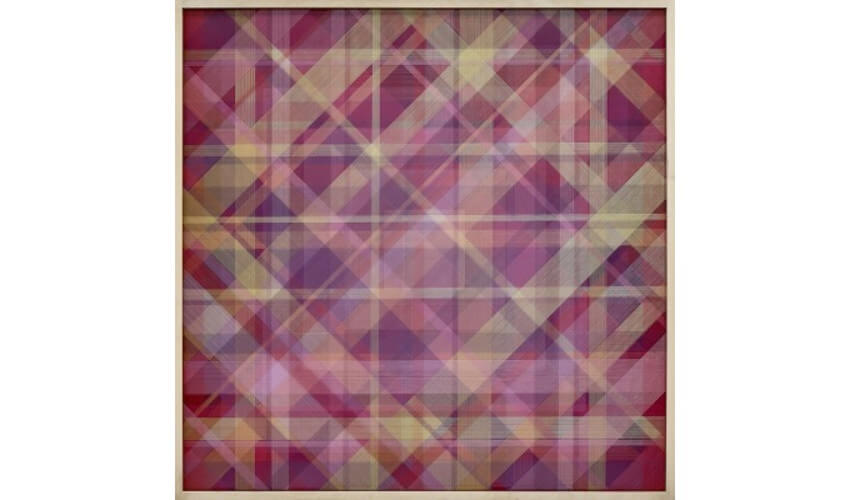

Jiang Weitao was formally trained in Shanghai. His oil paintings are luminous. They evoke the visual language of the grid, but they come about through a process similar to repetitive writing, in which each day new layers of lines are laid down, building up gradually to create patterns that extend beyond the limits of their individual marks. And finally, Gu Benchi is a self-trained artist whose paintings consist of hand woven lines of painted thread. The threads interweave across each other, building toward geometric linear patterns. What look at first like painted marks on a surface are in fact physical materials that have accumulated into a sort of surface. The conceptual implications of these works fascinates me, as they play with the notion of two and three-dimensionality, as well as that of the supposed difference between surface and line. And in addition to painting, Gu Benchi also extends this technique to make sculptures and large-scale installations. For this exhibition, he created a window installation, which transformed the clear glass facade of the gallery into a work of art.

Jiang Weitao - Lease of Life, 2017, 2017, Oil on board, 76 x 76 cm

Jiang Weitao - Lease of Life, 2017, 2017, Oil on board, 76 x 76 cm

Insignificant Forms

To me, it is obvious that all of these artists are mostly interested in the personal experience they undergo when they make their work. That experience is far more important to them than the objects that result from their efforts. The most revealing aspect of what curator Zhui had to say about this exhibition was his reference to Clive Bell, the 20th Century British art critic, and his “significant forms.” Bell believed in “aesthetic emotion.” He felt that if we could understand what qualities inspired humans to feel aesthetic emotion, we could finally discover what differentiates art objects from other kinds of objects. He considered a “significant form” to be one that stirred or awakened an aesthetic emotional response. As Zhui points out in his writing, the works in this exhibition are not objects intent on stirring emotion, but are rather objects revelatory of processes, and the passage of time. They are intended to be used in a contemplative process, through which we have the opportunity to understand relationships—between us and the art; between us and the artist; between the art and the universe; or between ourselves and everything.

Liu Wentao - TBC, 2012, Pencil on linen, 150 x 150 cm

Liu Wentao - TBC, 2012, Pencil on linen, 150 x 150 cm

In other words, these artworks are insignificant forms. They are not the point. They are revelatory of a point. But because they are abstract they do not explain what that point might be, nor are they critical of what a viewer might interpret it to be. They came about through a series of human actions involving materials and processes that can be explained; yet their effect transcends concrete description, and their meaning and purpose is unclear. This show and its accompanying writing revealed to me a broad, transcendental understanding of the word abstraction. It is not one that is completely lacking in Western Modernism. It is one that is an expression of something ancient and universal, albeit impossible—and perhaps unnecessary—to define.

Gu Benchi - Endless Line no 17, 2013, Polyester yarn line, stainless steel nail, acrylic adhesive, acrylic, 180 x 180 cm

Gu Benchi - Endless Line no 17, 2013, Polyester yarn line, stainless steel nail, acrylic adhesive, acrylic, 180 x 180 cm

Featured image: Gu Benchi - Endless Line no 56, 2017, Polyester yarn line, stainless steel nail,acrylic adhesive, acrylic, 100x 120 cm

All images courtesy 10 Chancery Lane Gallery

By Phillip Barcio