A Spotlight on Clinton Hill at Frieze New York

May 9, 2018

A solo exhibition of the work of Clinton Hill was one of the most buzzed about presentations at the 2018 Frieze Fair in New York, though many who saw it had to confess they had never heard the name of this artist before. Mounted by Los Angeles-based Royale Projects, the exhibition consisted entirely of paintings and drawings Hill made in the 1960s. The works had never been exhibited in public before. They declared themselves as fresh, idiosyncratic, and contemporary. What everyone who has since written about them has said boils down essentially to one word: important. They were luminously light in their color palette; they demonstrated a spatially complex understanding of negative space; and their nuanced shapes and compositional choices were so fresh it seemed to many spectators that the works could have been painted yesterday. They are contemplative, experimental, and subdued. They show a curious, relaxed side of Hill. And most of all they declare themselves as the most visionary, most delightful, and possibly most significant works Hill ever created. But those people who happened to have been already familiar with Hill and the various phases of his aesthetic evolution had something additional to say about these works—that they look almost nothing like anything they had ever seen by Hill in the past. A recent retrospective exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art that followed the entire known trajectory that Hill followed included examples of the primitivist abstraction he explored early in his career, a few pictures from his foray into Color Field painting later one, and then works representing his deep dive into dynamic, calligraphic, Wassily Kandinsky-esque, musically-inspired abstraction that began in the 1980s. These paintings at Frieze did not fit any of those phases. It was indeed a mystery—one that came with a fascinating story of lost treasures, accidental discoveries, and poetry unexpressed.

Rolled Gold

Clinton Hill passed away in 2003. Though not famous enough to be considered a household name, by the time he died he had built quite a successful career for himself. Collectors and museum curators knew him because he had been exhibiting his work continuously in galleries, museums and at art fairs for more than 50 years. Many younger artists knew him because he had been a painting professor at Queens College at the City University of New York for two decades. And many important artists knew him because he had been close friends with some of the most influential American abstract artists of his generation, including Jay DeFeo, Helen Frankenthaler, and Mark Rothko. One question many people have about him today is that if Hill was clearly a talented painter and was so well liked and well connected, why was he not more famous? The answer could simply be because of his work. He explored much of the same ground as his more influential contemporaries, in a capable, interesting, but not particularly revolutionary way.

Clinton Hill - Untitled, 1968. Print on paper. Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift from the Clinton Hill / Allen. Tran Foundation. GMOA 2012.365

The body of work that was shown this year at Frieze, however, is indeed revolutionary. It is instantly compelling, and some would say iconic. It masterfully expresses both a personality and an aesthetic vision that places Hill undeniably alongside Rothko, Frankenthaler, and DeFeo. But that only led to the question: Why had no one ever seen it before? Where has it been all these years? It turns out the works are part of a trove discovered in 2016—13 years after Hill died. According to Marilyn Pearl Loesberg, a former trustee of the Clinton Hill / Allen Tran Foundation, the works were found while a crew was cleaning out a storage facility. Workers noticed two rolls of canvasses wrapped up in paper and leaned in a corner. When they opened the rolls, they were stunned at what they saw—this entire body of work, which Hill had evidently created in the 1960s but not shown anyone. “We could hardly believe our eyes,” Loesberg said. “Color-saturated, light infused, magical paintings that no one knew existed.”

Clinton Hill - Untitled, 1988. Oil and wood on canvas. Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift from the Clinton Hill / Allen. Tran Foundation. GMOA 2012.368

The Forces of Life

It is unknown why Hill did not exhibit these canvases at the time he made them. Perhaps he saw them as experimental studies; or maybe the various forces of life that he was struggling with simply got in the way. Hill was openly gay at a time when society was antagonistic towards homosexuality. Some people speculate that these images convey a distinct feminine sensibility. Perhaps that was something Hill thought might work against them, but then how can we know for sure? Hill is known to have temporarily moved to Phoenix in the 1960s when a family member became ill. While there he worked in the music business. Maybe these paintings grew out of that experience, and had some personal relevance that Hill wanted kept private.

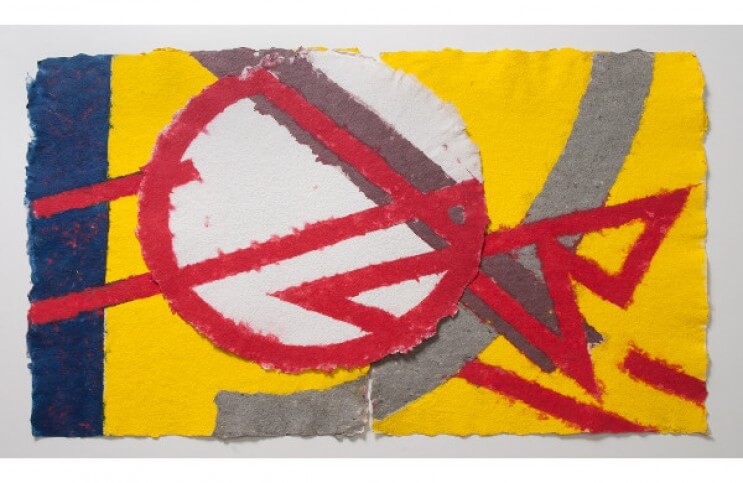

Clinton Hill - Untitled, 1992. Handmade paper construction Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift from the Clinton Hill / Allen. Tran Foundation. GMOA 2012.362

What is certain is that this body of work, with its lyrical, light-hearted, sensual, and harmonious aspects brings fresh elucidation to an essay Hill wrote in 1968 about the marriage of art and poetry. He wrote, “Art and poetry cannot do without one another. Art — the creative or producing, work making activity of the human mind. Poetry — that intercommunication between the inner being of things and the inner being of the human self which is a kind of divination. Such an emotion transcends mere subjectivity … and so induces dream in us. Unexpressed significance, unexpressed meanings ... play an important part in an aesthetic feeling and the perception of beauty.”For now it is a mystery how the best work of his life remained rolled up in a corner of a storage facility for half a century. But these newly discovered paintings at least finally reveal the true genius of Clinton Hill, and their rediscovery is truly a poetic expression of “the beauty of what is unexpressed.”

Featured image: Clinton Hill - Untitled, 1981. Handmade paper construction Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia; Gift from the Clinton Hill / Allen. Tran Foundation. GMOA 2012.366

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio