The Beauty Found in Cubist Portraits

In 1878 Margaret Wolfe Hamilton, in her novel Molly Bawn, coined one of humanity’s most beloved sentiments: “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” Three years later Picasso was born. Though Hamilton died of typhoid fever a decade before one was painted, her words seem tailor-made for cubist portraits. Although many who first saw them were shocked by them, and even found them hideous disfigurations, to many others cubist portraits were the perfect manifestation of something transformative, something beautiful and something new.

Early Cubist Portraits

For Pablo Picasso, the portrait was a favorite subject throughout his career. When he and Georges Braque were in the earliest stages of developing cubism, they focused on the landscape, the still life and the portrait as their key subjects. Braque spoke about their quest to portray space. Was there something about the human face that perfectly leant itself to such a quest? Or perhaps human features leant themselves particularly well to dissection along multiple linear planes, or to the portrayal of multiple viewpoints.

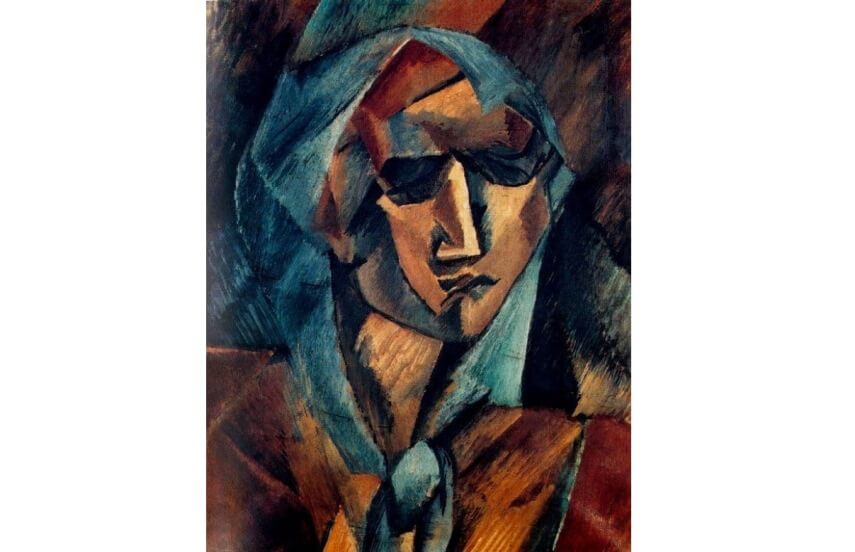

Georges BraqueHead Of A Woman, 1909, Oil on canvas, 33 x 41 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France

Georges Braque – Head of a Woman

One of the first cubist portraits was Head of a Woman, painted by Georges Braque in 1909. This subject matter and exact title would be returned to numerous times by both Braque and Picasso, manifesting as paintings, collages and even sculptures. In Braque’s initial exploration of the subject matter, we see the essential elements of cubist thought explored in simple, elegant detail. The eyes shown from above are mournful, while the face held high shows fortitude and quiet strength. Seriousness comes through in the shadow of her brow while the softly shaded blue moonlight on the right side of her lips reveals a sensuous kindness.

With Head of a Woman, Braque not only succeeds in capturing multiple points of view and creating a sense of time and space, he uses each of the different vantage points to explore simultaneous elements of his subject’s character. As one of the earliest cubist portraits, this work also stands out for its lush color palette. As time went on the cubist palette became more monotone, but here in this image we have rich blues, reds, yellows and browns inhabiting the same image, adding a straightforward richness and warmth to the piece.

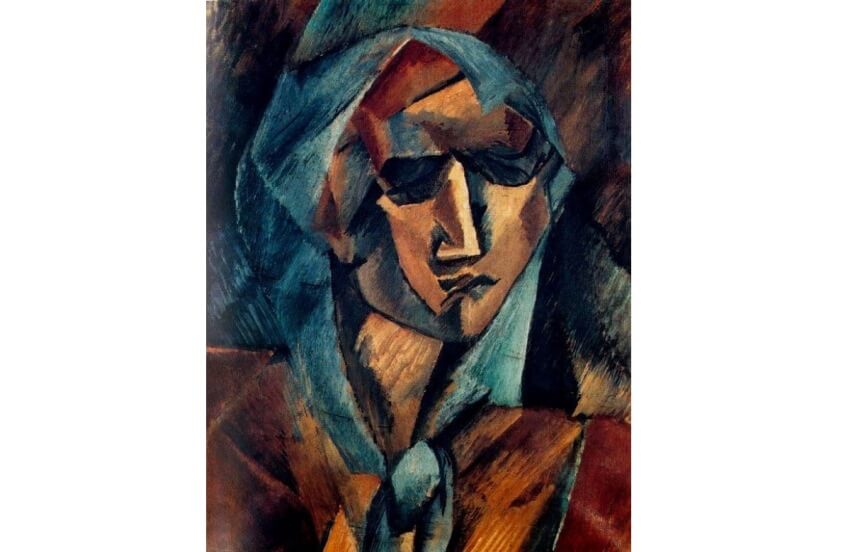

From that same year we have this Picasso portrait, also titled Head of a Woman. The general mood of the piece combined with the pursed lips and certain elements of the lighting suggest it could be the same woman, from the same sitting. But Picasso’s choices of which spatial planes to darken and which to lighten, and which characteristics to bring into view dramatically change the demeanor of the subject. In the eyes, sadness. Seen from below, the shoulders seem slumped, despairing. Seen from multiple simultaneous angles, the face is contorted in bewilderment.

As with Braque’s Head of a Woman from the same year, this piece by Picasso contains a relatively vivid color palette, incorporating yellows, greens, oranges and blues. The beauty of this piece is in its darkness, and its brooding, atmospheric qualities. Picasso uses simultaneity not to demonstrate a range of emotion or a multiplicity of character traits, but instead uses different points of view to show a relative sameness, a cumulative sadness evident from every angle.

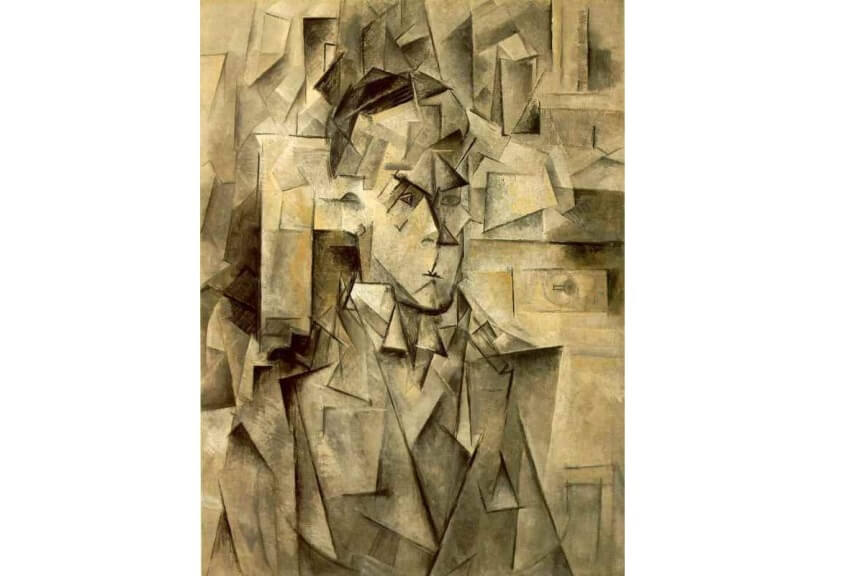

Pablo Picasso - Portrait of Wilhelm Uhde, 1910, Oil on canvas, 81 x 60 cm, Joseph Pulitzer Collection

Picasso's Early Portraits

In 1910, Picasso painted this portrait of one of his earliest collectors, the art dealer Wilhelm Uhde. When Picasso painted this portrait, Uhde already owned a significant number of his works, including at least three cubist portraits (Buste de femme, Seated nude and Girl with a Mandolin). In his portrait of Uhde, as in his earlier Head of a Woman, Picasso uses simultaneity to convey a cumulative sense of a single emotion in his subject. Whichever point of view he draws from seems to add up to one thing: seriousness.

This portrait demonstrates the reduced color palette that quickly took over the cubist oeuvre in these years. The simplified palette focuses our attention entirely on the subject, and also allows another essential element of cubism to be more fully appreciated: the use of line. In this portrait we see how each line responds to every other line, puling each other inward toward the emotional vortex of Uhde’s scrunched face. The two-dimensional flatness creates a subtle sense of forward movement while the lines simultaneously create a comical sense that the subject is collapsing in on himself.

Pablo Picasso Head of a Woman, 1909, Oil on canvas, 60.3 x 51.1 cm,Museum of Modern Art, New York

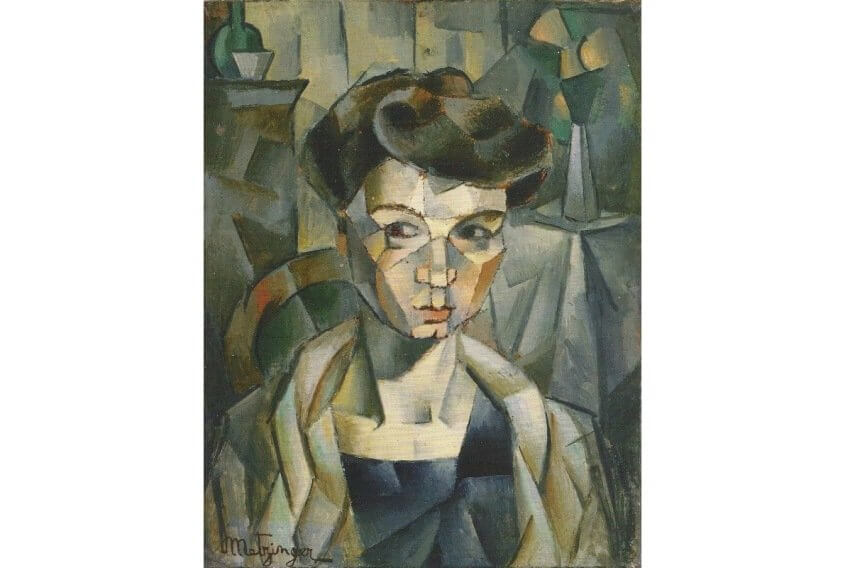

Jean Metzinger and Juan Gris

Jean Metzinger was a divisionist painter who made the switch to cubism early in the style’s development. An avid writer, he became one of cubism’s top theorists, comparing its approach to the depiction of space to theories in non-Euclidian mathematics. In this portrait from 1911, Metzinger achieves a unique sense of dimensionality. By selective placement of dashes of color and use of a limited number of perspectives he somehow depicts two, three and four-dimensional space. The work seems flat, and yet the subject also seems to emerge outward from the surface, and at the same time she feels like she’s in motion, moving through space, turning.

A friend of Picasso and Braque since 1906, Juan Gris took the cubist theories in a unique aesthetic direction sometimes referred to as crystalline. In this portrait Gris painted of Picasso, the various points of view have a uniform nature to them, as though pulled from different reflections from the surface of a diamond. His limited color palette, rather than dulling the image, provides a sense of luminosity. And though flatness is vital to this piece, his choice of where to focus his blues adds an artificial effect indicating Picasso is in the forefront, which makes sense for this obvious homage.

Jean Metzinger - Portrait of Madame Metzinger, 1911, Pencil and ink on paper, 22.6 x 15.7 cm, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Beauty and the Cubist

It’s easy to imagine how a world conditioned to a particular type of aesthetic beauty could have rejected the idea that these early cubist portraits were beautiful. But with hindsight we can see the profound ways these works helped shift the culture’s eyes away from seeking beauty only in subject matter. In these works we find beauty in line, in shading, in forms and in dimensionality. We discover emotional connections with the elements of painting, not just the subject matter. Aside from the inherent beauty of these works, there is also something beautiful about that.

Featured Image: Juan Gris - Portrait of Picasso, 1912, Oil on canvas, 36.73 in x 29.29 in, Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio