Geometric and Vanguard Art of David Bomberg

Jul 27, 2016

Enthusiasm is a vital substance in art. Exciting work is something every viewer, collector, gallerist and curator craves. While some rare artworks just inherently possess their own excitement, enthusiasm most often originates with artists. Something within them – their passion, their curiosity – simply manifests in the work. David Bomberg may have been the most enthusiastic artist to come out of Britain in the first quarter of the 20th Century. His experiments with form and composition were so avant-garde they caused his expulsion from London’s prestigious Slade School of Art. But even despite that rebuke, rather than be discouraged Bomberg flourished, proving himself to be explosively creative, an expert draughtsman, and an enraptured seeker of new ideas. The bold, Modernist images he made in the years leading up to World War I offer a unique glimpse of the unbridled excitement and energy of that optimistic age.

Who’s David Bomberg?

A tragic irony plagues many great artists. To become successful in the art market you have to make interesting, saleable work, and to make interesting, saleable work you must be creative, open and individualistic; but not too creative, open and individualistic. Artists that are too far head of the intellectual pack often get ridiculed. As the saying goes, “pioneers get slaughtered, settlers get rich.” Salability is also helped when an artist is associated with a larger movement that art sellers and buyers can contextualize and understand. The irony lies in the fact that truly creative, open-minded individualists often find it intolerable to associate themselves with movements that have defined objectives or stringent aesthetic ideals. They find manifestos to be restrictive. They like to keep their options open. So it goes that many brilliant creatives get left out of the history books and die in poverty, all because they staunchly remained true to themselves, staying experimental to the end in order to feed their own curiosity and enthusiasm.

Bomberg was one such artist. When you research Vorticism, the first thing you might notice is that the movement’s founder was Wyndham Lewis, one of the most prominent names in 20th Century English art and literature. But then you’ll see that the movement’s most famous, iconic image, The Mud Bath, was painted by David Bomberg. Bomberg never joined the Vorticists. He experimented with some of the same aesthetic concepts, and made some paintings that appear to be in the same visual wheelhouse, but Bomberg’s interests were far more expansive than the Vorticists’ limited concerns. Wyndham Lewis, however, enjoyed a lifelong fame, almost entirely due to the momentum he incurred by his founding of Vorticism. Bomberg, the non-Vorticist painter of Vorticism’s best painting, died in obscurity, penniless.

Essential Pure Form

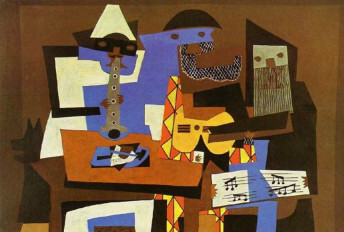

What Bomberg’s work had in common with Vorticism was rooted in formalism. Vorticism’s aesthetic borrowed from two other existing Modernist styles. It married Cubism’s abstract geometric shapes with the hard lines and brash colors of Italian Futurism. The concept behind the movement was to express movement and modernity. Bomberg’s interests were also initially related to the city and to machines, but his use of Vortisist-esque imagery was incidental. He wasn’t focused so much on achieving any specific look as he was in achieving the right feeling. As he put it, his desire was to “translate the life of a great city, its motion, its machinery, into an art that shall not be photographic, but expressive.”

The visual language he created was based on the reduction of form. He felt that the best way to express the nature of his subjects was to simplify them to their most basic states. In that way he hoped to reveal something vital about their essence. Bomberg’s painting Vision of Ezekial, painted in 1912, achieved that balance he sought of abstract reduction of form, figurative vitality and expressive emotion. It combined his interest in highly simplified imagery with the legends of his Jewish family heritage, creating both a mythic and Modernist aesthetic vision uniquely his own.

An Intenser Expression

Not satisfied that he had taken the reduction of forms to its limits, Bomberg continued experimenting. One of his early instructors, an artist named Walter Sickert, had imparted to Bomberg the importance of painting his subject’s “gross material facts.” That approach had assisted Bomberg in the development of his impressive representational drawing skills. But it held him back from his interest in subjectivity. Rather than simply endeavoring to show precise characteristics of his subjects, he felt that it was equally important to express his personal reaction.

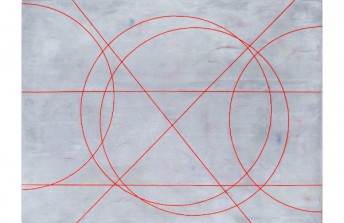

In a series of figure compositions he exhibited in 1914, Bomberg intentionally eliminated all “gross material facts.” In the artist statement accompanying that exhibition he wrote, “I appeal to the Sense of Form…I completely abandon Naturalism and Tradition. I am searching for an Intenser expression…where I use naturalistic Form, I have stripped it of all irrelevant matter. I look upon nature, while I live in a steel city. Where decoration happens, it is accidental. My object is the construction of Pure Form. I reject everything in painting that is not Pure Form.”

A Revolution Toward Mass

Expanding on his focus on pure form, Bomberg delved deeper into abstraction. In his painting titled Procession, he reduces a line of human figures to such essential forms the image nearly becomes a complete geometric abstraction. The shapes take on expressive qualities that bring to mind a range of associations, from high-rises to coffins.

Bomberg continued to evolve, diverging into a series of paintings resembling stained glass windows that have been shattered and then pieced back together. In the Hold and Ju-Jitsu feature image planes divided into a diamond shaped grid. Rather than creating a composition from reduced forms, Bomberg uses the grid and the surface itself as form. The resulting images resemble Op Art in their ability to trick the eye and pull the viewer into illusionist space. Unlike his earlier works their sense of mass comes from an expression of feeling achieved entirely through formal, non-representational means.

The Spirit in the Mass

At the outbreak of World War I, Bomberg was drafted into service. His experiences in the infantry, watching his colleagues, supporters and family members get shredded by mechanized weapons, destroyed his fascination with the machine age. When war ended, he resumed painting, but adopted a far more organic, painterly technique. His new direction caused him to be utterly ignored, and forgotten by the art world of his time.

Bomberg struggled financially throughout the rest of his career, but traveled extensively and never stopped painting. He continued to experiment with the tactile qualities of paint, focusing on the powerful emotive potential of texture and brushstroke. Whether painting abstractions, landscapes or figurative works, he remained devoted to pursuing what he called “the spirit in the mass.” He knew that through variations in the thickness and stroke of paint and open-minded exploration into a subject’s most essential form, the truest expression of a subject could be conveyed. In defiance of rejection and commercial defeat, his tireless enthusiasm for painting allowed him the rare gift of connecting with the essential quality of things, and translating it for those of us who otherwise may not be able to see.

Featured image: David Bomberg - Procession, 1912-1914, Oil on paper laid on panel, 28.9 x 68.8 cm, The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, © The Estate of David Bomberg

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio