What Was The Dematerialization of Art Object?

Lucy Lippard—giant of American art criticism, author of more than 20 books, and co-founder of Printed Matter, the quintessential seller of books made by artists—turned 80 this year. Despite her multitude of other accomplishments, Lippard is best known for “The Dematerialization of Art,” an essay she co-authored in 1968 with John Chandler (available online here.) In the essay, Lippard presented evidence that art might be entering a phase of pure intellectualism, the result of which could be the complete disappearance of the traditional art object. The piece grew out of, and helped contextualize, the preceding decade or so of wildly inventive conceptual art, which often left behind only ephemeral, non-archival relics, or no relics at all other than perhaps recordings of experiences. Conceptual artists were devoted to making ideas the central focus of their work, and many argued convincingly that the objects artists make in order to express their ideas are nothing but waste products, and that the ideas themselves are the only things worthy of consideration. The essay was enormously influential at the time: so much so that Lippard followed it up with a book called Six Years, extensively analyzing evidence of the trend. But obviously in the long run her premonition was inaccurate, since art objects still have yet to dematerialize. Nonetheless, in celebration of the upcoming 50th anniversary of the original publication of The Dematerialization of Art, we thought we would take moment to delve into this influential essay and highlight what about it is relevant for our time.

The Science of Art

Lippard based the core concepts she discussed in The Dematerialization of Art on an idea first laid out in a book called The Mathematical Basis of the Arts, written by the American painter Joseph Schillinger. In that book, Schillinger divided all of art history into five categories of aesthetic phenomena. First, he explained, came the “pre-aesthetic” phase of mimicry. Next came ritualistic or religious art. Then came emotional art. Then rational, empirical-based art. And then the fifth, and allegedly “final” aesthetic phase described by Schillinger was “scientific,” or what he called “post-aesthetic.” This final phase, he predicted, would culminate in the “liberation of the idea” and lead to the “disintegration of art.”

While contemplating the evolution of art throughout the 1950s and 60s, Lippard believed what she was witnessing was the emergence of this fifth phase of art. And she was excited about the notion. She considered dematerialization a positive, vital shift. After all, if the aesthetic object could cease to exist as the central focus of art then art could be freed from commodification, the often vile system that exerts so much destructive force on the lives and work of many artists.

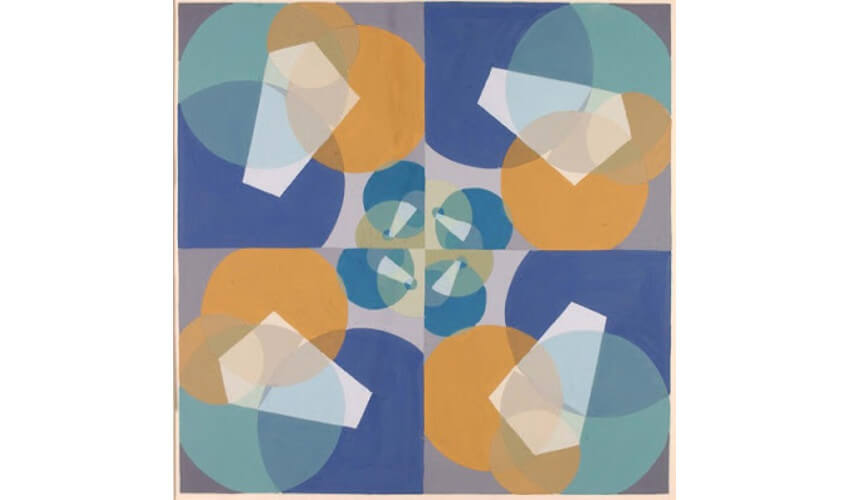

Joseph Schillinger - Green Squares, from series, The Mathematical Basis of the Arts, ca. 1934, tempera on paperboard, Smithsonian, photo via rendaan.com

Joseph Schillinger - Green Squares, from series, The Mathematical Basis of the Arts, ca. 1934, tempera on paperboard, Smithsonian, photo via rendaan.com

The Science of Commodities

As evidence that dematerialization had begun, Lippard cited movements such as Light and Space, which were visual in nature but not object-based, and Minimalism, which drastically pared down the aesthetic object. Such movements she believed diminished the importance of the visual aspect of an artwork, defining the visual as more of a jumping off point for an immaterial, intellectual experience. But one of the early, and obvious, criticisms of The Dematerialization of Art was that even though these ephemeral, conceptual concepts were less object-based, they still nonetheless results in physical phenomena. Even a performance artist creates a thing—a performance—which can be sold as an experience, or recorded.

No matter how slight a relic an artist creates, it can become fetishized and traded as a commodity. The only way to completely avoid the possibility of commodification is to never share an idea: then perhaps the reverence and sanctity of the intellectual experience can be preserved. But only shared ideas can truly be called art. And as soon as an idea is shared, it can be possessed, manipulated, and expressed in other ways, or in other words, materialized. And as soon as something materializes it can be bought and sold as a commodity.

Joseph Schillinger - Unfinished Study in Rhythm, Series developed from The Mathematical Basis of the Arts, ca. 1934, crayon and pencil on illustration board, sheet: 14 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches (37.78 x 50.48 cm), Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

Joseph Schillinger - Unfinished Study in Rhythm, Series developed from The Mathematical Basis of the Arts, ca. 1934, crayon and pencil on illustration board, sheet: 14 7/8 x 19 7/8 inches (37.78 x 50.48 cm), Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

The Five Phases

Re-reading The Dematerialization of Art today, the only true error that seems evident is how it presents the five phases of art, as explained by Schillinger, as something linear. It is always tempting for each generation to see itself as standing on the forefront of modernity. Schillinger thought art had been progressing historically through phases, and Lippard thought she was part of the generation that was advancing art toward its evolutionary apex. But time does not move forward; it just passes. Culture is not linear; it repeats itself. Humanity devolves as rapidly as it is evolves. And the truth was in the 1960s and 70s, and still is today, that artists are finding ways to dematerialize as rapidly as others are rediscovering how to materialize it.

Ultimately, Lippard must have also realized this even as she wrote on the topic of dematerialization, because her essay concludes by asking if the so-called zero point in art is likely to be reached soon. The answer, she states, is, “It hardly seems likely.” Even today as artists sell virtual creations that exist only in digital space, we can still argue dematerialization is a fantasy. Anything that can be seen is by definition material, even if it can only be seen through virtual reality goggles. But in our opinion that only proves that perhaps achieving dematerialization was never really the point. The point Lippard was truly making was simply that one important aspect of visual art is to engage tirelessly in the search to discover how to express more with less. Any artist working toward dematerialization is also working toward simplicity. And simplicity leads to the discovery of what is truly indispensable, and thus truly meaningful. That is definitely not the final phase of art. But it is one that is capable of reminding us what the value of art truly is.

Featured image: Joseph Schillinger - Red Rhythm (detail), Series developed from The Mathematical Basis of Ars, ca. 1934, gouache on paper, image area: 8 x 11 15/16 inches (20.32 x 30.32 cm); sheet: 10 1/2 x 13 7/8 inches (26.67 x 35.24 cm), Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio