How Die Brücke (The Bridge) Celebrated the Power of Color

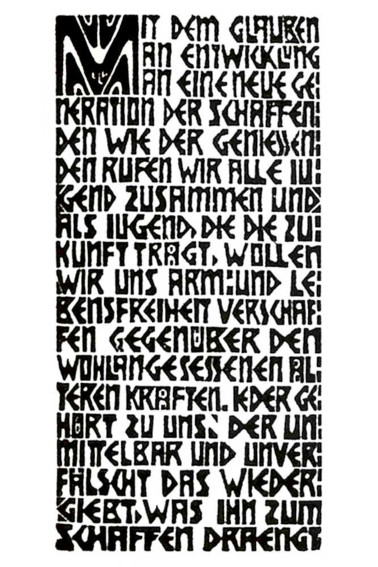

German Expressionism was born in the city of Dresden in 1905. That is when four architecture students came together to establish Die Brücke, an artistic movement intended to start a German aesthetic revolution. Die Brücke is German for “The Bridge.” The phrase conveys the perception the group had of themselves as transitional figures, connecting the outdated German art traditions of the past with Modernist ideals that would lead the culture into the future. Broadly speaking, the Die Brücke aesthetic tended towards emotionally expressive compositions dominated by pure, flat, ungradiated fields of color, and simplified forms made with primitive marks. Die Brücke artists sought to communicate feelings rather than copy reality. Their aesthetic was largely inspired by woodcut printing. But there was also another, earlier inspiration for the group – something ironically not German, and not from their century: the paintings of Vincent Van Gogh, a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who had died in 1890. The four founders of Die Brücke – Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Fritz Bleyl and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff – visited a Van Gogh retrospective that opened in Dresden in 1905. They were not yet painters at the time, but they became enthralled by what this visionary artist was able to communicate with paint. The colors, the rapid brush strokes, and the simplified forms had an electrifying effect on them. His example pointed them to a way of tapping into the underlying passions of life. So influential was Van Gogh to Die Brücke that one of the later members to join the group – Emil Nolde – actually tried to convince them to change their name to “Van Goghiana.” Happily, they did not follow this suggestion. To accept such a change would have been the death of a movement that was above all else based on originality. Sure, Van Gogh inspired them, but what Die Brücke truly sought was not copy someone else, but to follow their own individual instincts. Those intentions are summed up in the third sentence of their three-sentence manifesto, released on a woodcut print in 1906, which stated: “Whoever renders directly and authentically that which impels him to create is one of us.”

An Organized Turmoil

To most turn-of-the-century Germans, the artists of Die Brücke seemed like wild men. When Franz Marc first saw an exhibition of their colorful, primitivist paintings, he dubbed them “the Fauves of Germany,” a reference to les Fauves, or “wild beasts,” a group of artists working at the same time in France led by André Derain and Henri Matisse who also employed luminous, unrealistic hues. The comparison to les Fauves was apt. In fact, Die Brücke was worthy of an even wilder reputation. They not only used outrageous colors in their paintings, they were wild in every sense of the word. They lived illegally in their studios, which were not zoned residential, hiding their beds in the attic during the day so as not to be caught. They also painted nude models in nature. Since no respectful, professional model would take such an assignment, they paid non-models to go with them into the woods, far from where they might be seen. Together with their amateur nude models and a cadre of other friends and lovers they partied and painted and swam, becoming one with their most artistic, most liberated, and most primitive natures.

The image of Die Brücke artists as being out of control, however, is not accurate. They were bohemians, but they were also one of the most organized and thoughtful art collectives in history. In the eight years of their existence they held more than 70 group exhibitions, both in Germany and abroad. The group was also innovative in terms of marketing savvy. They sold subscriptions, so viewers who wanted to own their work but who could not afford to buy a painting could receive posters, prints, and other ephemera, such as printed manifestos. The group was staunchly rigid in their own membership requirements: no member was allowed to show their work except at group exhibitions. The immense organizational talent that was needed to pull off so many exhibitions while also managing memberships and subscriptions is undeniably impressive. For all their reputation as wild men, Die Brücke established a revolutionary, and immensely effective organizational structure – one still imitated by many art collectives and artist run galleries today.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner - Manifesto of the Brücke Artists Group (Programm der Künstlergruppe Brücke), 1906. Horst Jähner: Künstlergruppe Brücke. Geschichte einer Gemeinschaft und das Lebenswerk ihrer Repräsentanten. E.A.Seemann, Leipzig 2005.

The Degenerates

Die Brücke began to splinter around 1912, when Max Pechstein, a late joiner, openly violated their membership agreement by showing his work in solo exhibitions. The nail in the coffin came in 1913, when Kirchner wrote his Chronicle of Die Brücke, which alienated the other members by claiming that he was their leader (when in fact the group was a loosely organized, almost anarchic assemblage of individuals). By a twist of history, however, the members of Die Brücke did not stay alienated forever. When the Nazis came into power, the work of Die Brücke artists was considered degenerate. The members were moved by these events to restate, at least in theory, their dedication to each other, and to the ideal for which they had stood: freedom and independence for artists.

After their inclusion in the Degenerate Art Show of 1937, many of the works of Heckel, as well as those of late joiner Otto Mueller, were destroyed. But their entire legacy was not lost. A few years before he died, Heckel donated what works of his remained to help establish The Brücke Museum, which opened in Berlin in 1967. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff also made a substantial donation of his works, and the museum has since acquired many other pieces from other members of the group. Today, its collection includes thousands of paintings, sculptures and works on paper. The colorful legacy of the group lives on in this collection, but it does not stop there. It echoes through the fabric of countless other expressionistic movements in the 20th Century, and through the contemporary art world today, as an example of the expressive power of color, and the revolutionary potential of authenticity.

Featured image: Karl Schmidt-Rottluff - Pharisees, 1912. Oil on canvas. 29 7/8 x 40 1/2" (75.9 x 102.9 cm). Gertrud A. Mellon Fund. MoMa Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio