Is Dot Painting the Remnant of Pointillism?

Nov 2, 2016

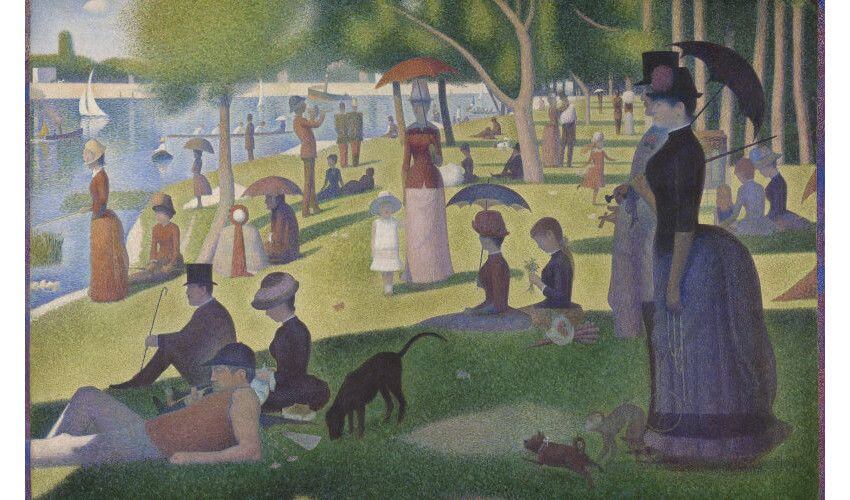

Dot painting may sound benign, but it has had a long, tendentious, sometimes controversial history. The Neo-Impressionist artist Georges Seurat shocked the art world with a dot painting in 1886. Not to say he made a painting of a dot, although Kazimir Malevich did decades later when he painted Black Circle. Rather, Seurat made a painting composed of dots—thousands of them. Called A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, it was the first example of a new technique Seurat had invented, which came to be known as Pointillism. Seurat based his dot technique on the theoretical writings of the physicist Ogden Rood. In his 1879 book Modern Chromatics, Rood described a theory called optical mixture, which postulates that from a distance human eyes mix colors together in order to create the perception of fields of solid color in the mind. In so doing so, Rood explained, the mind perceives more luminous and vivid colors than what truly exist. Seurat hoped to create the same effect on a painting by placing tiny dots of unmixed colors beside each other in hopes that from a distance viewers would mix the colors in their eyes and perceive a more luminous and vibrant combination than he could otherwise have premixed. The reviews of A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte were not good. Critics were outraged, and it even reviled many avant-garde artists. But for a few visionaries it harkened the dawn of a new age. Today, dot paintings help define the oeuvres of a multitude of artists. Are these the contemporary intellectual progeny of Seurat and the Pointillists? Or are they simply admirers of the proud and humble dot: the tiny proto-form of the most iconic symbol in the human aesthetic lexicon—the circle?

Contemporary Dot Painting

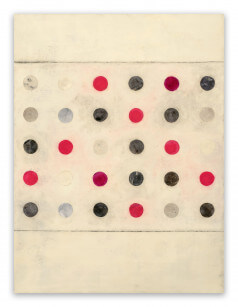

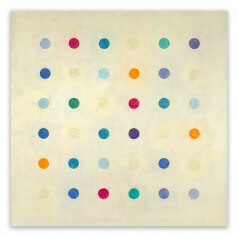

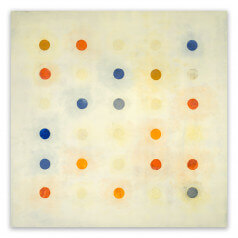

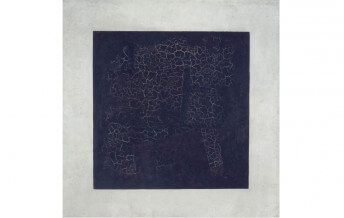

Most dot painters today approach their relationship with the dot from a personal point of view. They are not only interested in the ability of dots to affect perception. They are also interested in the formal aspects of the dot, like its value as a shape, and what it can communicate in terms of color and composition. The British artist Damien Hirst has painted thousands of dot paintings over the course of his career. He uses the dot as a way of exploring color. He says his dot paintings offer an opportunity to engage with color contrasts and combinations free from other concerns. Like the early 20th Century Suprematists, Hirst uses circles, albeit small ones, to communicate purity.

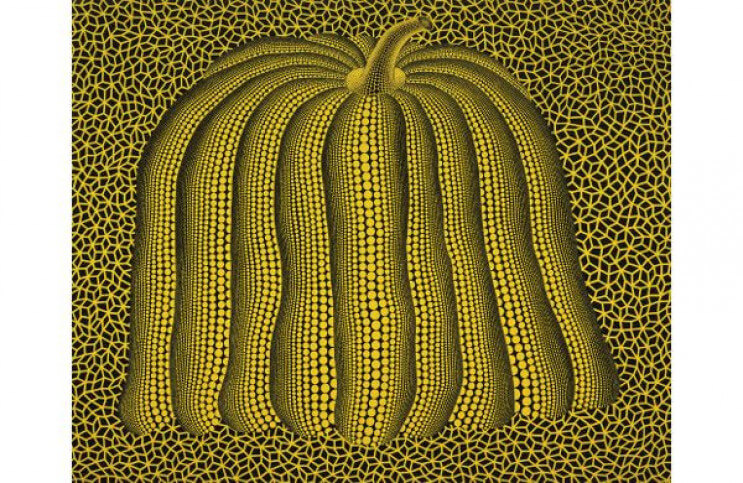

Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama approaches dots from more of a metaphysical perspective. She incorporates polka dots into her work as three-dimensional forms, as subject matter, as content, and as transcendental symbols. She covers surfaces in polka dots, makes polka dot covered clothing and even fills entire environments with dots. Says Kusama, “A polka-dot has the form of the sun, which is a symbol of the energy of the whole world and our living life, and also the form of the moon, which is calm. Round, soft, colourful, senseless and unknowing. Polka dots can't stay alone; like the communicative life of people, two or three polka dots become movement... Polka-dots are a way to infinity.”

Damien Hirst - Spot Painting. © Damien Hirst

Damien Hirst - Spot Painting. © Damien Hirst

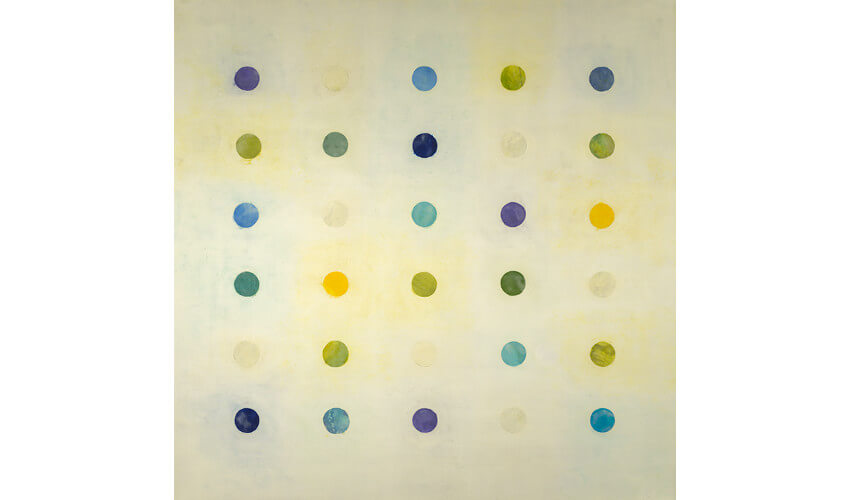

Rhythm, Culture and Dots

California-based abstract painter Tracey Adams considers dots to be revelatory. A trained music conductor, she uses dots individually and in patterns in her paintings as a way of communicating rhythms, and to provide balance and symmetry in her visual compositions. On the contrary, some other artists use dots to hide content and meaning in their paintings. When Australian Aboriginal artists first began painting spiritual canvases in the 1970s, they were concerned that by painting their images on canvas rather than in the sand, as they had done for centuries, outsiders would gain understanding of their secret rituals. So they invented a unique aesthetic language based on dots, which they use in their paintings to hide their sacred imagery.

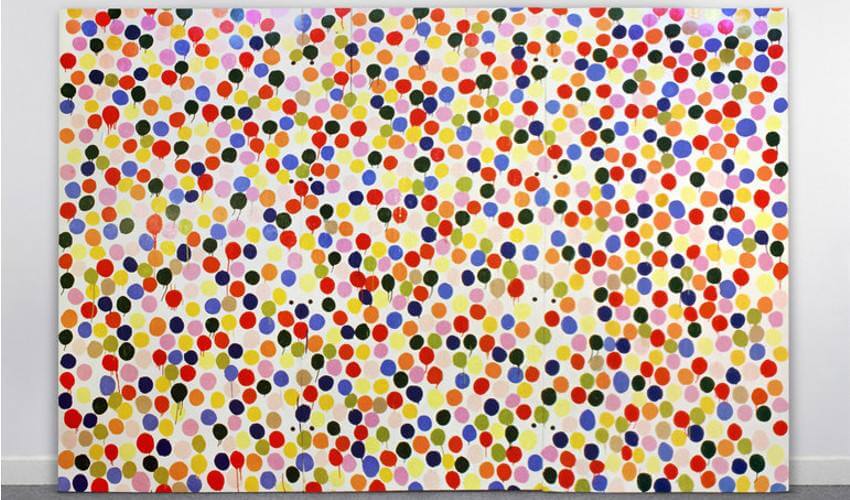

Roy Lichtenstein may be one of the most well known, and more controversial dot painters of the Modernist age. In 1961, he began producing paintings that mimicked comic books. The paintings incorporated the original Ben-Day dots from the comics, which are used in printing as an inexpensive way to provide color to images. He blew the comic images and the Ben-Day dots up to a giant size, making the dots a major aesthetic component of the work. But they were not important for their ability to provide color or shading, but for their reference to modern technology and Pop culture. Critics ridiculed Lichtenstein, not for his dots but because he was appropriating low culture for his art. As with Seurat, they were threatened by his challenge to the established hierarchy of taste.

Roy Lichtenstein - Seductive Girl. © The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Roy Lichtenstein - Seductive Girl. © The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein

Polka Dot Dreams

The story of whether these Modernist and contemporary dot painters are connected to the legacy of Pointillism begins about 50 years before Georges Seurat painted A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte. It begins with the origin of the polka dot. Around 1835 a dance known as the Polka originated in what is now the Czech Republic. In musical notation, the rhythm of a polka is expressed as a series of evenly spaced, single beamed notes. On sheet music they look like symmetrical patterns of dots. Within a few decades of the Polka spreading through Europe and the United States, the polka dot pattern started appearing on textiles and clothing, and by the 1870s it was ubiquitous.

Claiming that Pointillism was inspired by a folk dance would be pure conjecture. But there might be a connection nonetheless. In 1879, an illustrator and printer by the name of Benjamin Day, Jr., had the idea for a new printing technique that would use small, identically sized dots to provide shading on a printed image. This technique would become known as the fore mentioned Ben-Day dots. So did Benjamin Day, Jr. notice the movement of polka dots on the outfits of Polka dancers, and become inspired by the color effect the spinning dots created? Maybe. Maybe not. In any case, Bed-Day dots pre-dated Pointillism by five years.

Tracey Adams - (r)evolution 36, Encaustic, collage and oil on paper, 2015. © Tracey Adams

Tracey Adams - (r)evolution 36, Encaustic, collage and oil on paper, 2015. © Tracey Adams

Getting the Point

When Georges Seurat first revealed A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte at the Salon of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in 1886, the most immediate controversy was caused by the fact that Seurat was approaching painting from a scientific, rather than an artistic point of view. The idea that artists should deconstruct the aesthetic experience along philosophical or technical lines caused a split between Neo-Impressionist artists. Some were inspired by the notion. Others found it sterile and academic.

But from the audience perspective, the main controversy was that, in the opinion of many viewers, Pointillism simply did not work. Seurat was proposing two things: first, that two existing colors would mix in the eye when seen from a distance and be perceived as a third, non-existent color; and second, that the perceived color would be more luminous and vibrant than if it had been premixed. Many viewers simply could not disengage from their intellectual awareness of the dots long enough to consider the alleged aesthetic effects. The shock of the new bogged them down in analytical dissection of the technique.

Georges Seurat - A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

Georges Seurat - A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte

The Point Is: Seurat Tried

Soon after inventing Pointillism, Seurat became much less of a purist. He evolved to use it as a complementary technique to more traditional methods of color blending. Perhaps he perceived that the technique was interfering with his images rather than illuminating them. But when we compare contemporary dot painters to the Pointillists, the main point is not whether Seurat was successful in demonstrating the theories expressed in Modern Chromatics. The point is that Seurat was successful in sparking something new. No sooner had Seurat begun to evolve his style toward a more expressive effect than the Divisionists arose to delve even further into the purely analytical notions Pointillism had raised. That split, between the analytical and the expressive, helped define and direct the complementary paths Modernism has taken since.

The legacy of Pointillism has influenced artists in ways that have nothing to do with dots. Damien Hirst is part of its lineage because he is seeking to understand color as a formal quality, separate from other concerns. Roy Lichtenstein is part of its lineage because he challenged the art world status quo. Tracey Adams and Yayoi Kusama are part of its lineage because they explore the way our eyes and our minds relate with patterns in the visual world. And maybe in some incredibly broad respect, all contemporary artists who reach for the unknown are in the lineage of Georges Seurat and the Pointillists, because they question how we can strive to discover the new.

Featured image: Yayoi Kusama - Pumpkin. © Yayoi Kusama

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Bracio