What is Conceptual Painting?

Every work of art was once just an idea in somebody’s head. That’s a funny thought considering how fleeting ideas can be, and how difficult it can be to turn even the best ideas into reality. Conceptual painting, as a field of artistic practice, attempts to confront the gap between ideas and physical reality. It considers the possibility that for every painting that ends up being hung on a wall, there are countless others that never made it onto the canvas, and countless alternative ways of painting the one that did make it up on the wall. It even goes so far as to say the painting may not matter at all; that the only thing that truly matters is the idea.

Just Think It

Sometimes the best way to get something done is to not think about it. Just do it, as the slogan says. When we do stop and think about the nature of what we’re doing, it can paralyze us, as we question whether or not what we’re doing is worth the effort, or has any value at all. When the first abstract painters began their quest to create purely abstract works, there was much thinking going on, and they were full of ideas. But simultaneously some artists were asking questions about the value of those, or any other ideas.

In 1917, Marcel Duchamp created a work of art titled “Fountain.” It was a urinal turned upside down and signed “R. Mutt.” Duchamp took an ordinary object and transformed it, in this case by turning it upside down and removing it from its utilitarian surroundings, rendering its original use obsolete and inviting unto it new possibilities for meaning. “Fountain” was rejected by the show to which it was submitted, but it became the benchmark for what would eventually come to be known as Conceptual Art, a tendency to place the value of an artist’s ideas above the value of the artist’s processes or objects.

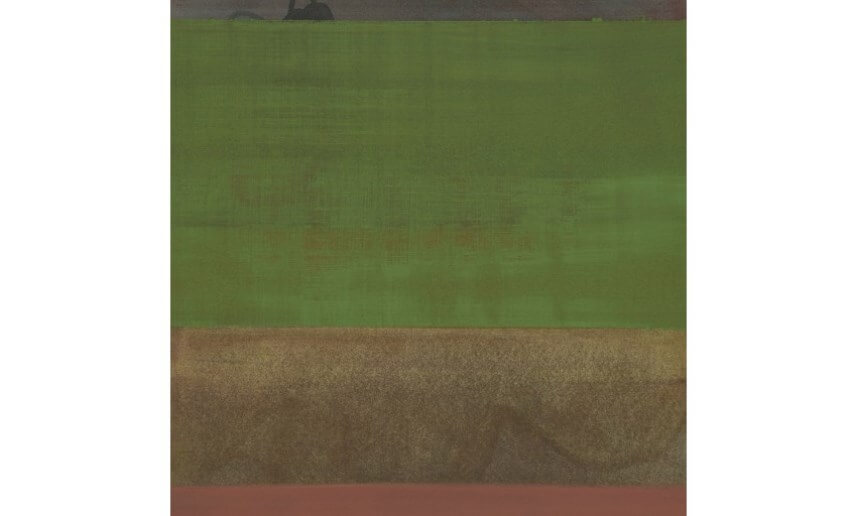

Sarah Hinckley - 2009, 15 x 9.8 in, © Sarah Hinckley

Image is Nothing

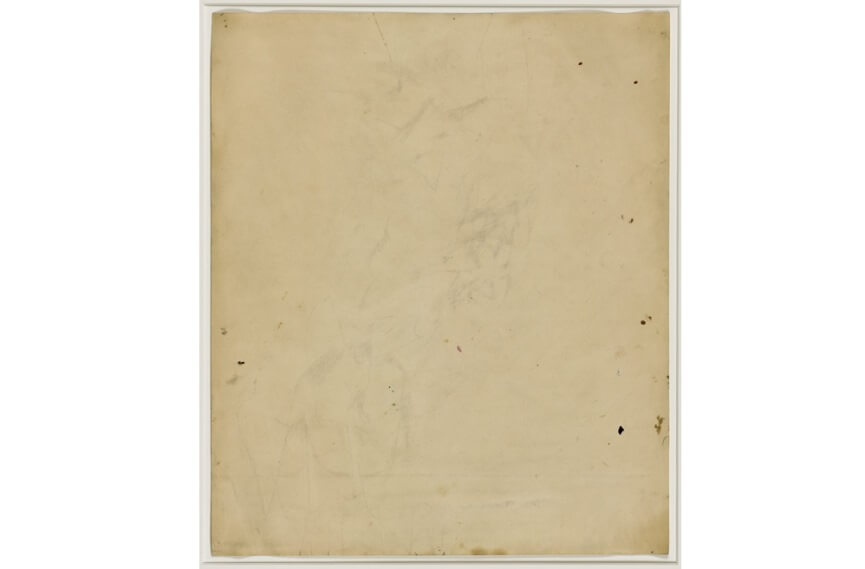

Many of the first conceptual paintings weren’t paintings at all. In 1953, the artist Robert Rauschenberg had the idea of erasing a painting. He intended to make the actual object disappear, leaving only the idea, and thus to elevate it to new reverence. He believed that in order to achieve the full manifestation of his idea, someone else needed to hold the object in esteem. He needed to erase the work of another painter otherwise it would just be like negating something that never was.

Rauschenberg turned to his friend Willem de Kooning and asked him to donate a beloved painting for his concept. Although de Kooning resisted at first, he ended up giving Rauschenberg, a drawing, one he hated to see disappear and that would be difficult to erase. Rauschenberg went through more than a dozen erasers over the course of more than a month, finally managing to erase the entire image. The result, called “Erased de Kooning Drawing,” confidently stated the notion that the idea of a work of art is what’s most important, and that the work need not exist at all.

Robert Rauschenberg - Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, Traces of drawing media on paper, 64.14 cm x 55.25 cm x 1.27 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), San Francisco, © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Making the Unseen

The notion of the primary importance of the idea spread rapidly across the western world. Artists began experimenting with every possible manifestation of an idea, believing that if an idea is to manifest, it can manifest in any number of ways. Art about a picture of a tree could manifest as a photograph of a tree, a painting of a tree, a drawing of a tree, an abstract painting of a tree, the words “picture of a tree” written on a surface, a performer pointing to an actual tree, an interpretive dance imitating a tree, or even an artist sitting on the floor with closed eyes thinking about a picture of a tree.

In 1958, the artist Yves Klein held a painting exhibition in Paris often referred to as “The Void.” The full title of the show was “The Specialization of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilized Pictorial Sensibility, The Void.” According to legend, more than 3000 visitors came to see the show. Upon entering the gallery, the viewers confronted a white room devoid of paintings, containing only an empty cabinet. Said Klein about the show, “My paintings are now invisible and I would like to show them in a clear and positive manner.”

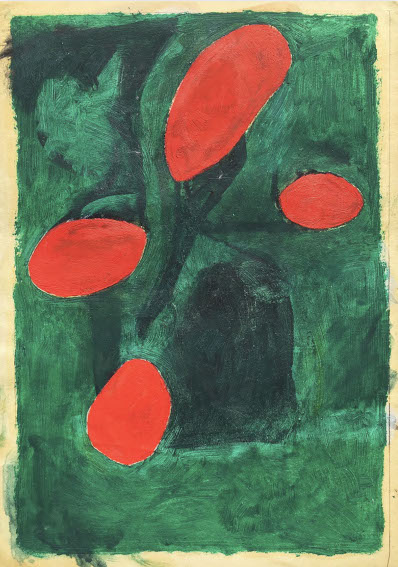

Fieroza Doorsen - Untitled (Id. 1281), 2017, Oil on paper, 27 x 19 cm.

SolLeWitt

In 1968, the abstract painter Sol LeWitt added another dimension to the realm of conceptual painting. He theorized that not only does it not matter if an idea ever manifests as a physical painting, it also does not matter how it gets painted or who paints it. All that matters is the artist’s original expressed idea of the painting. As a demonstration of this concept, LeWitt began designing wall murals that could be, and usually were, executed by people other than himself.

LeWitt’s idea was that each individual hand would draw each line differently, so even though they would be working from the same plans, each artist would draw the mural differently than everyone else. The finished products would vary from the original design and from each other, but since the original design is all that matters the variation is irrelevant, as are the means of production. The legacy of LeWitt’s idea is that his conceptual wall paintings are still being reproduced today, after his death.

John Monteith - The Night Sky, 2010, graphite on hand-made paper, 24 x 17.7 in, © John Monteith

The Future of Ideas

Contemporary conceptual painting continues to expand our appreciation of the ideas that form the basis of a work of art. The work of the contemporary American abstract painter Debra Ramsay is rooted in ideas that are fundamental to our time. Her process is to track the changing colors of nature, such as those of seasonal flora, and then analyze those color changes in a computer program. The resulting data is used to create a palette that references the changing natural colors. She then uses that palette to create an abstract representation of objects in space changing over time.

Ramsay’s work brings to mind two fundamental ideas that dominate our current culture. The first is the idea of data, and the notion that every aspect of our lives is being monitored, digitized, calculated and analyzed in some monumental quest for understanding. The other is the idea that nature is changing, and that we may now only be able to watch that happen and somehow find aesthetic beauty in it. Ramsay’s ideas are beautifully rendered in the form of abstract paintings, but it is the ideas themselves that make her work so relevant to our culture now.

Debra Ramsay- A Year of Color, Adjusted for Day Length, 2014, Acrylic on polyester film, 39.8 x 59.8 in.

H7

The Canadian abstract painter John Monteith works in a number of different mediums as he searches for the most successful physical manifestation of his artistic concepts. One realm he often explores is that of text. Monteith extracts bits of text from other sources he happens to encounter while working, such as the daily news or a book or a conversation. He then presents the text out of context in a gallery environment, which invites new conceptual interpretations of the ideas contained within the words.

By drawing on multiple media sources for the text he uses in the works, Monteith’s text-based drawings bring a contemporary viewpoint to the works of 1st generation conceptual artists such as Robert Barry, who also often works with text. Barry’s work involves displaying bits of text on paper, canvas, walls, floors, or any other surface suitable to the idea. His words are often his own, but sometimes are taken from other texts, and they are presented in a way as to invite new associations and meanings. Often, these conceptual works present far more information than a traditional painting could by requiring the participation of the viewer’s own imagination.

Matter and Meaning

In 1965, in a seminal work of conceptual art called One and Three Chairs, the conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth presented an actual chair, a photograph of a chair and a written description of what a chair is. Like so many other conceptual works, it brought to the forefront the question of what the difference is between ideas, objects and abstractions.

We now accept that a conceptual painting need not be a painting, nor need it exist in material form at all. But when it does exist, is that important? Does it matter that it’s here, in the physical realm? Is there really no difference between the object and the idea? Do we truly value the idea more? If we were starving would we rather have a recipe, a painting of food, or actual food? In practical terms, conceptual painting both asks and answers one of humanity’s most important questions: Does it matter what we do?

Featured Image: Robert Barry - Untitled (Something which can never be any specific thing), 1969, Typewriting on paper, 4 x 6 in., © Robert Barry

All Images used for illustrative purposes only