Why Was Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square Painting So Seminal?

Aug 8, 2018

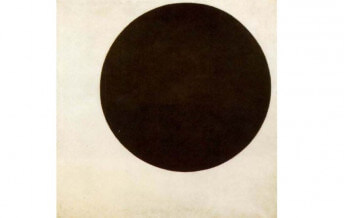

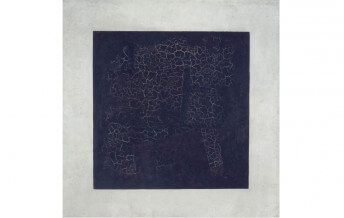

For the past several generations, art historians have been telling people that the painting “Black Square” (1915), by Kazimir Malevich, was the most important, most seminal painting of the 20th Century. Measuring a relatively small 79.5 cm. x 79.5 cm., the painting simply features a black square painted upon a white surface. As uncontroversial as that may sound, the first time it was exhibited it caused an uproar. It was purported to be the first purely abstract painting to be publicly exhibited in the Western world. Prior to painting it, Malevich had become well-known for painting in the Cubo-Futurist style, which leaned towards abstraction but still referred to the natural world. “Black Square” threw all story telling, all figuration, and all natural imagery out the window. It was an ultimate expression of reductionism: a declaration that all recognizable visual imagery can be pared down to the simplest possible forms, and that content is irrelevant; all that matters is feeling. Malevich himself called “Black Square” the “zero point” of art. When he first exhibited it, he hung the painting in what is known in Russia as the “beautiful corner,” where the wall meets the ceiling, which is usually reserved for religious icons. Malevich evidently considered “Black Square” to be sacred: a symbol for a new, Modern sort of spirituality. But was this painting truly seminal? Was it as important as we are led to believe? Every generation must decide for itself what is important and why. We must decide logically whether we should continue to revere “Black Square,” or whether it is finally time to challenge the inherited myth of its importance.

Was It Really the First?

The primary conceit underlying the alleged importance of “Black Square” painting was that it was a first—a complete original with no precedent in art history. As the Tate Modern reports in its article “Five Ways to Look at Black Square,” Malevich handed out pamphlets at The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10, where he first exhibited “Black Square” in 1915, which read, in part, “Up until now there were no attempts at painting as such, without any attribute of real life… Painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself.” Clearly Malevich thought he had seized new artistic ground. And based on all of his other writings, we have no reason to doubt the sincerity with which he held this belief. But was he correct?

The assertion Malevich made, that painting had never before been an end in itself, seems impossible to prove. Malevich may have done it most prominently, but to say that his accomplishment was unique in all of human history is hyperbolic. In 2015, on the 100th birthday of “Black Square,” Russian scientists analyzed an early version of the painting. (Malevich ultimately painted at least four.) Beneath the top layer of paint, they found hidden writing that seems to convey a racist joke. It says, “Negroes battling in a cave,” an apparent reference to the title of a drawing by a French writer nearly 20 years earlier, which shows a black rectangle on a white surface. Was Malevich making the same ignorant joke? Was he making a note to himself? We do not know. Regardless, there is something intrinsically interesting, and even quite funny, about this comment that he wrote on the painting, though it is not the joke he likely intended. The comment calls to mind contemporary discoveries of the earliest known paintings made by human hands, which indeed happen to have been scrawled on the walls of caves, in prehistoric Spain. Those paintings include abstract black lines, which bare no resemblance to the natural world—the true “zero point” in art, 60,000 years before Malevich was born.

Kazimir Malevich - Black Square, 1915. Oil on linen. 79.5 x 79.5 cm. Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

The True Importance of Black Square Painting

If “Black Square” was not really a first, why was is important? To discover the answer to that question, we need to look beyond its marketing campaign. A painting is not important just because the artist, or a critic, or a dealer, says it is. The importance of “Black Square” must be contained within the painting itself. For me, the painting is important because of the simplicity of the image. I see in it something that I recognize as elemental. It looks simultaneously symbolic and meaningless. It is representative of geometric thought, aesthetic thought, and architectural thought. It is a balanced image. It allows color and form to speak for themselves. To me, “Black Square” is equivalent to hearing a single perfect note played on a violin, or feeling a light breeze on my skin on an otherwise still day. It is an expression of something universal, which has more to do with experience than with aesthetics.

But was it seminal? I do not know if I would use that word. Nowadays, words like seminal are overused to the point where they have little meaning. Every artist is described by their gallerist as important. Every big exhibition is called monumental. Every new thing an artists does is called a discovery. To call “Black Square” painting seminal might be just like so much puffery. Malevich was just an artist—a very thoughtful one, nonetheless, who wrote a lot of interesting things for us to consider. “Black Square” may not be seminal, but it is a painting that I feel like I want to be close to. It is undeniably attractive, both visually and esoterically. Something does not have to be seminal in order to have value. I propose that instead of rating paintings like “Black Square” with hyperbolic marketing adjectives, we instead simply use our words to describe what it objectively is, and what it means to us as individuals. If it somehow could teach us to restrain our urge towards hype, and to talk about art in more straightforward, everyday terms, that actually would be seminal.

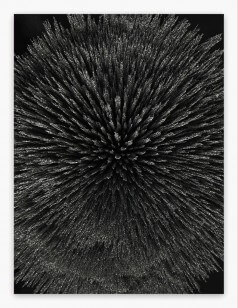

Featured image: A section of Suprematist works by Malevich exhibited at the 0,10 Exhibition, Petrograd, 1915

By Phillip Barcio