Suprematist Composition - The Visual Manifesto of the Russian Avant-Garde

Since the mid-1800s artists have written more than 60 major manifestos. Each identifies a specific set of concerns and artistic practices. With these written manifestos artists were communicating to the entire world their aesthetic intentions and making clear who’s with them and who’s against them. Suprematist Composition (Blue Rectangle Over Red Beam), a painting by the Russian artist Kazimir Malevich, is a sort of visual manifesto. Although Malevich wrote a 4000+-word essay explaining Suprematism’s philosophies and goals, all of the concepts and concerns outlined in it are also visible in the visual language of this one painting. All we have to do is learn how to read it.

The Suprematist Composition Code

The language of Suprematist Composition (Blue Rectangle Over Red Beam) consists of paint, surface, geometric shapes and primary colors. It communicates that there’s something more pure, more universal and truer than the images of the natural world. As Malevich's written manifesto says, “I have destroyed the ring of the horizon…To reproduce beloved objects and little corners of nature is just like a thief being enraptured by his legs in irons. Things have disappeared like smoke; to gain the new artistic culture, art approaches creation as an end in itself and domination over the forms of nature.”

When we decipher the language of this painting and understand its statements, we connect with universalities rather than specifics. We comprehend the concepts of space, movement, form, togetherness, isolation and relativity. We notice similarities and differences but that there is no hierarchy of importance between the aesthetic elements. We see shapes stripped of their symbolism. We see a composition that’s open to introspective interpretation rather than being burdened by objective meaning.

This single painting announces a separation from history. It announces Malevich’s intention to make a new art for a new world. Even after a careful reading of Malevich’s written Suprematist manifesto, From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism: The New Realism in Painting we can see that this painting communicates it all, and in some ways says it more clearly and directly.

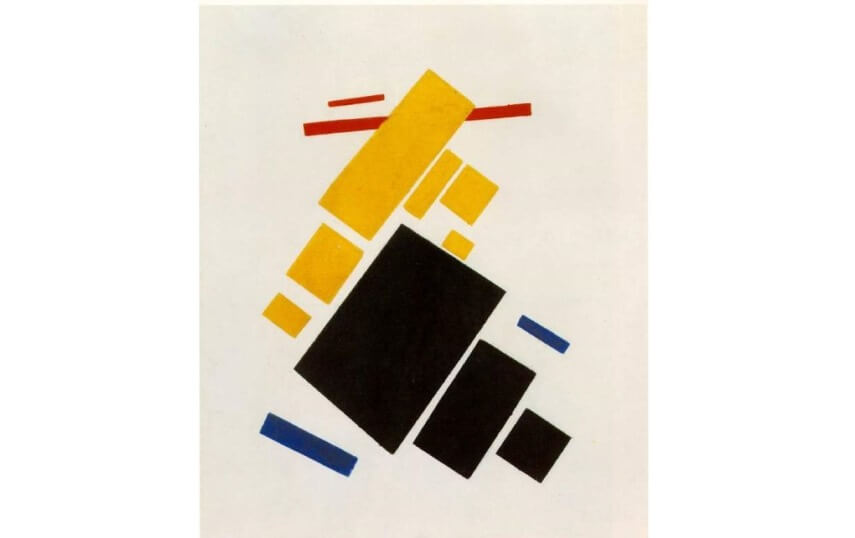

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying, 1915, Oil on canvas, 23 x 19 in, Museum of Modern Art, New York

A $60 Million Miracle

That this painting has survived long enough to inspire us is a bit of a miracle. Malevich painted Suprematist Composition (Blue Rectangle Over Red Beam) in 1916, in the middle of World War I and just one year before the outbreak of the Russian Revolution. The painting was part of a massive creative output through which Malevich was attempting to create what he called “a pure living art.” By working entirely abstractly , painting universal geometric forms that had no relationship to the figurative external world, he was challenging the ego-driven, individualistic power struggle that he believed had led the world to the brink of self-destruction.

Malevich exhibited this painting multiple times but resisted selling it. He held it in his personal collection until 1927. That’s the year, when after exhibiting it in Berlin, he entrusted it with a friend, Hugo Häring, a German architect. Häring protected the painting throughout WWII, saving it from annihilation during the Nazi campaign to destroy “degenerate” art. When Malevich died in 1935, Häring still had the painting. He eventually sold it to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, where it remained for 50 years. Then, after a 17-year legal battle, Malevich’s heirs won possession of it and subsequently sold it through Sotheby’s in 2008 for $60 Million, making it the most expensive work of Russian art in history.

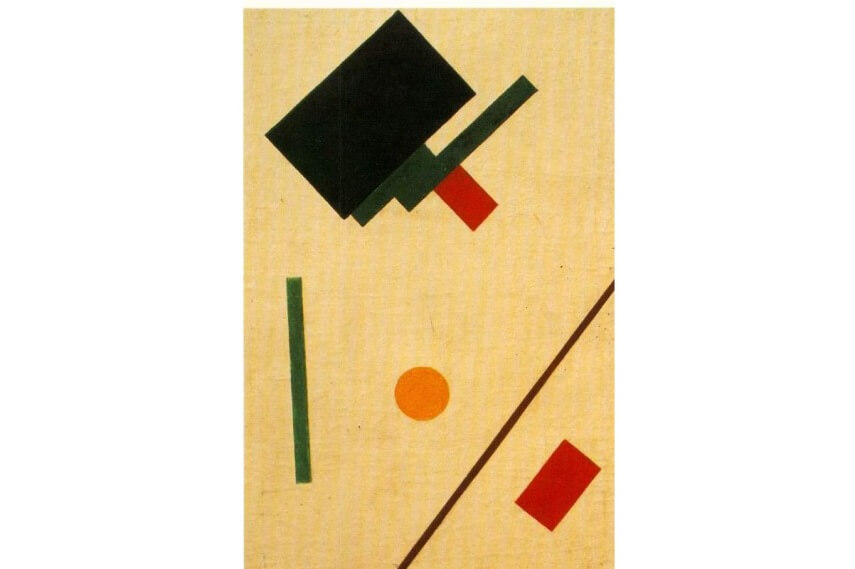

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition, 1915, Oil on canvas, 70 x 47 cm, Fine Arts Museum, Tula

Other Suprematist Compositions

But Suprematist Composition (Blue Rectangle Over Red Beam) wasn’t the only painting with that title. Malevich painted a large number of paintings that he titled Suprematist Composition. It was as though he intended for them to be seen as a visual dictionary expressing the details of the aesthetic language he was inventing. By analyzing them all we can expand our Suprematist literacy, the same way we might read novels generated in a written language we’re endeavoring to learn. Each of these works expands our Suprematist vocabulary, deepens our understanding of its goals and allows us to more intimately enjoy all of the Suprematist works.

From the Suprematist Manifesto:

“…between the art of creating and the art of copying there is a great difference…The artist can be a creator only when the forms in his picture have nothing in common with nature.”

When Malevich’s paintings were first exhibited they caused a stir because they had no apparent subject matter. They held no reference to nature. In the above work are squares, rectangles and other seemingly lifeless forms. They do however seem to move. They seem alive. Like primordial things they represent a new beginning. Although they’re simple, in context with their time they’re truly creative.

From the Suprematist Manifesto:

“Forms must be given life and the right to individual existence…this is possible when we free all our art from vulgar subject-matter and teach our consciousness to see everything in nature not as real forms and objects, but as material masses…”

Each form in the above Suprematist Composition has an existence of its own, an outer life that suggests an inner life. The forms are isolated and yet they exist in a composition: individual forms in harmony with each other, together expressing an ideal.

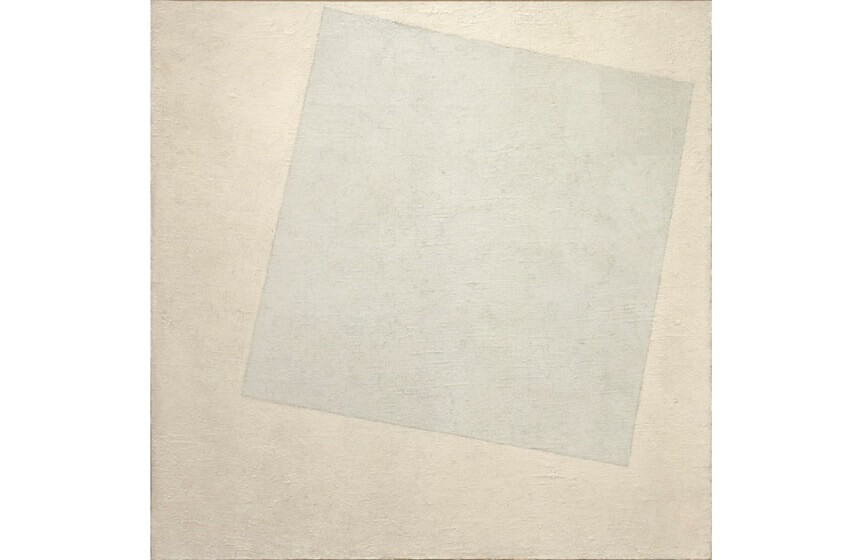

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition: White on White, 1918, Oil on canvas, 31 x 31 in, Museum of Modern Art, New York

From the Suprematist Manifesto:

“Color and texture in painting are ends in themselves. They are the essence of painting, but this essence has always been destroyed by the subject. The square is not a subconscious form. It is the creation of intuitive reason. It is the face of the new art. The square is a living, royal infant. It is the first step of pure creation in art. Before it, there were naive deformities and copies of nature. Our world of art has become new, non-objective, pure.”

Truly Malevich’s most powerful statement was made in his square paintings. In what is without question one of the simplest works we see the final purity of Suprematism: a white square painted on a white surface. We see paint, surface, color and form, and nothing else. It’s pure, innocent, revolutionary considering its time, and it’s the embodiment of the Suprematist ideal.

Featured Image: Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition, 1916, Oil on canvas, 88.5 × 71 cm, Courtesy of Christie's.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio