The Daring Artists of the Russian Avant-Garde

Picture two kids on a merry-go-round. One is Art, the other History. Most of the time History pushes and Art rides along, occasionally commenting, “Too fast,” or “Too slow.” But once in a while, Art pushes and History goes along for the ride. The Russian Avant-Garde emerged in a time between when the Russian Empire was in collapse and the Soviet Union was on the rise. For that all-too-brief time, between about 1890 and 1930, creativity and originality held sway over the Russian intelligentsia, and Art took control of the merry-go-round. Though the impact of the Russian Avant-Garde’s ideas is barely visible in the modern day Russian Federation, the global legacy of their genius endures.

The Seeds of the Russian Avant-Garde

To understand Russian Avant-Garde artists, it helps to contextualize Russia’s past. Anyone who’s ever seen a globe knows how massive Russia is. And by the mid-1700s, it wasn’t only one of the world’s largest countries, but was also one of the most populous. The vast majority of that population was rural. Even as late as 1861, when Tsar Alexander II finally emancipated them, as many as a fifth of all Russians were agricultural serfs.

Russia had been a monarchy since its inception. But the enormous technological and social changes wrought by the second half of the 19th Century created circumstances that doomed that system of governance. By the dawn of the 20th Century, that Russian society was on the brink of massive change was obvious. The question was which form that change was going to assume. So it came to pass that a practical society that had never had much of a need for abstract creative thought suddenly found itself looking to the avant-garde for inspiration.

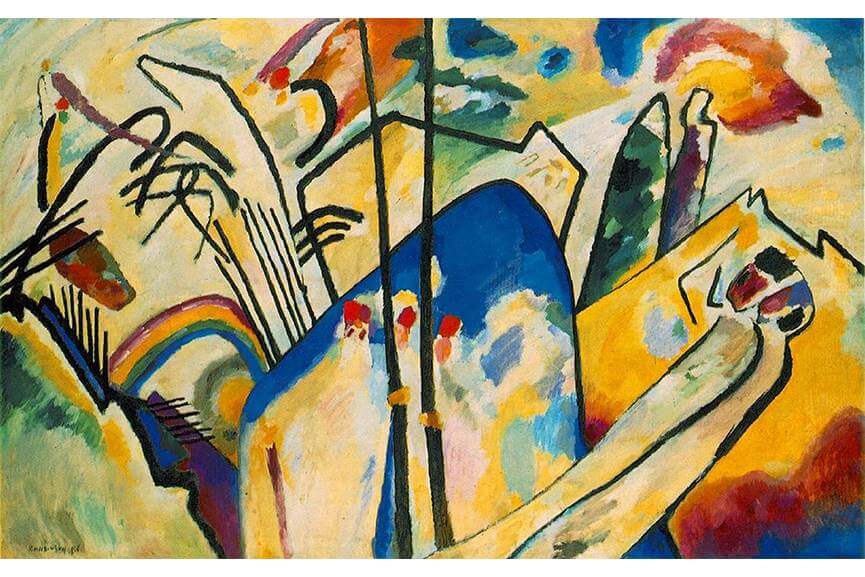

Wassily Kandinsky - CompositionIV, 1911. Oil on Canvas. 159.5 x 250.5 cm, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf, Germany

Supreme Being

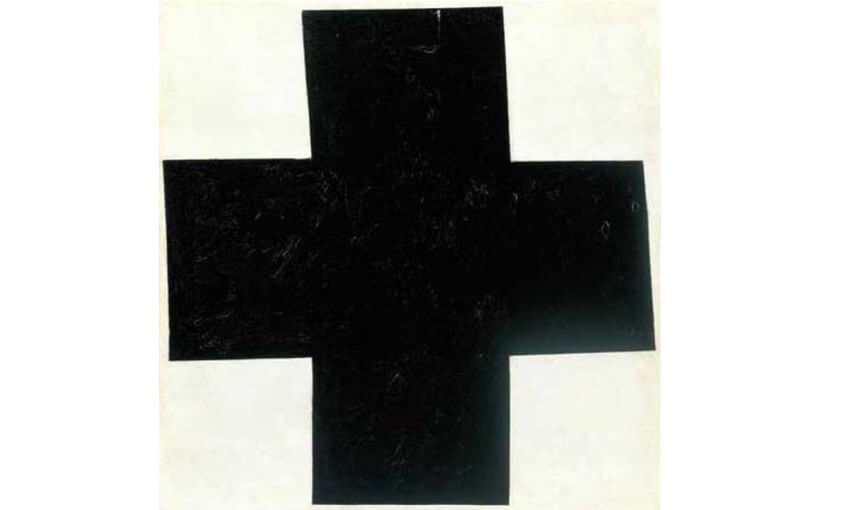

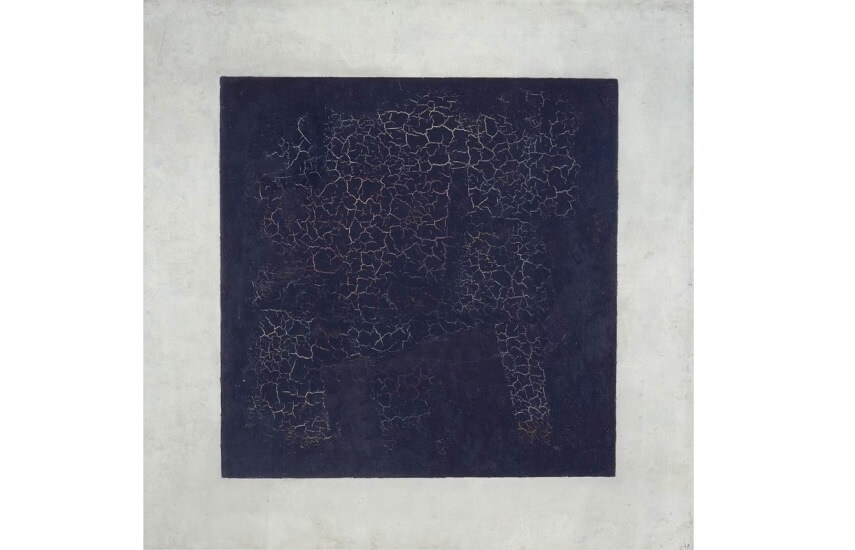

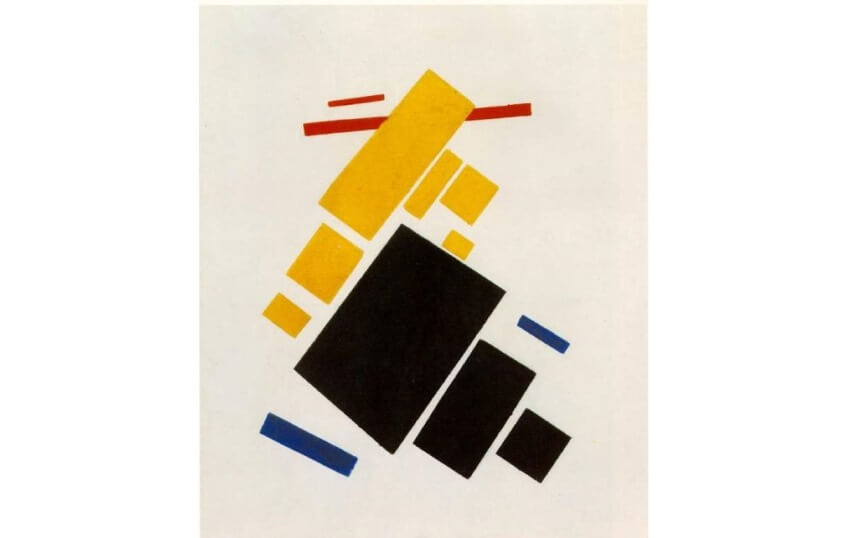

One man who was eager and able to rise to the occasion was an artist named Kazimir Malevich . Trained as a representational artist, Malevich had been experimenting with Cubism and Futurism in an effort to discover an aesthetic that was worthy of the modern world. He found what he was looking for in a movement he invented called Suprematism, an aesthetic based on flat, two-dimensional geometric shapes. He called his geometric abstract style Suprematism because he believed it represented the supreme pictorial expression.

Previously Russian culture, and especially Russian art, had been predicated on the idea that artists should in some way represent the objective world. Suprematism was purely abstract, and therefore open for interpretation. This concept, that viewers were free to interpret art according to their own intellect, was both novel and threatening. Malevich was suggesting that there was more to the world than objective reality, and that individuals should think for themselves: in Russian historical terms, two revolutionary ideas.

Kazimir Malevich - Black Cross, 1915, Oil on canvas, 80 x 80 cm, State Russian Museum

The Spiritual in Art

Together with Malevich at the top of the Russian Avant-Garde ladder was Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky is regarded as the first purely abstract painter in modern history. Although recent revelations suggest that at least two other artists were painting abstract works decades before Kandinsky, most nonetheless regard Kandinsky as a pivotal figure in both Abstraction and Modern Art in general. Largely, that’s both because of his painting and his writing.

Kandinsky’s seminal book “Concerning the Spiritual in Art” discusses at length his intellectual pursuit to develop a purely abstract painting style. He compares his quest to instrumental music, which expresses emotions, mental states, feelings and abstract thoughts without representational language. Kandinsky wrote about his desire to achieve a non-representational visual style that could, like music, communicate the spiritual universalities of human existence. Like Malevich, Kandinsky was a revolutionary merely by suggesting that humans could achieve something deeper and more important through creativity, individuality and freedom of thought.

Kazimir Malevich - Black Square, 1915, © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Do Something Constructive

At the same time as Malevich and Kandinsky were exploring the deeper meanings and universalities available in abstraction, other members of the Russian Avant-Garde were exploring an almost polar opposite type of abstract art. Known as Constructivism, this style was based on the same geometric abstract language that Malevich used, but it was put towards a completely different goal. The aim of Constructivist art was to be of use. The Constructivists rejected Wassily Kandinsky because of his embrace of spirituality. Malevich derided Constructivism because of its propagandist goals.

One of the most endearing figures of Constructivism was the Russian Avant-Garde artist and architect Vladimir Tatlin. He’s remembered not for what he did, but for what he failed to do. After the revolution, he designed a model for Tatlin’s Tower, what was intended to be a colossal monument to the Bolsheviks. It would have been 400 m tall, 76 m higher than the Eiffel Tower. It was intended to convey optimism, industrial superiority and the bright Russian future that lay ahead. But it was never built. The steel wasn’t available following World War I, and anyway the design was structurally unsound. In hindsight, Tatlin’s unrealized tower is the ultimate Constructivist monument. It exposed its society’s weaknesses. What could be more useful to understand, and therefore to be able to overcome?

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition Airplane Flying, 1915, Oil on Canvas, 22 7/8 x 19 in, MoMA Collection

Kazimir Malevich - Suprematist Composition Airplane Flying, 1915, Oil on Canvas, 22 7/8 x 19 in, MoMA Collection

The Missing Link

Many art historians end their list of Russian Avant-Garde artists with Malevich, Kandinsky and Tatlin . But someone who often gets left off the list is a woman named Aleksandra Ekster, an artist who was in many ways a vital link between Russia and Western Europe during the Avant-Garde’s most important years.

Every major Russian Avant-Garde movement blossomed around 1913. Five years prior, in 1908, Aleksandra Ekster first left Russia to study art in Paris. There, she befriended Pablo Picasso and George Braques, who introduced her to other French artists and intellectuals of the time. She was profoundly influenced by their ideas, taking them back with her to Kiev, St. Petersburg and Moscow, and sharing them with, among others, Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky and Vladimir Tatlin. Ekster was a vital connection between the Russian and Western European intelligentsias. Perhaps she gets forgotten because she never settled on one particular style. She stayed open, independent, creative and experimental. She remained Avant-Garde.

Wassily Kandinsky - Black Spot I (detail), 1912, Oil on canvas, Saint Petersburg, The Russian Museum

The Soviet Reality

Thanks to the international efforts of these key members of the Russian Avant-Garde, the entire modern art world has been forever enriched. But in Russia, the only lasting influence was that of Constructivism. Thanks to that movement’s practicality, it fit in with what’s called Soviet Realism, which was Stalin’s vision of what the fledgling Soviet Union needed, or rather demanded, from its artists.

In the early 1930s, Soviet State orders dictated that all art was to be useful to Russian society. The core tenets of Soviet Realism were that all art must be proletarian (relevant and understandable to workers), typical (composed of everyday genre scenes), realistic (in the traditional, representational sense), and partisan (supportive of the official State and Party goals). And so with that, History reasserted itself on the merry-go-round and Art once again was just along for the ride. Thankfully, the ideas and influences of the Russian Avant-Garde survived elsewhere, influencing every Modern art movement to come, and continuing to inspire contemporary artists who long to experiment and break free from the ideas of the past.

Featured Image: Wassily Kandinsky - Untitled (First Abstract Watercolor), 1910, Watercolor and Indian ink and pencil on paper, 19.5 × 25.5" (49.6 × 64.8 cm), Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio